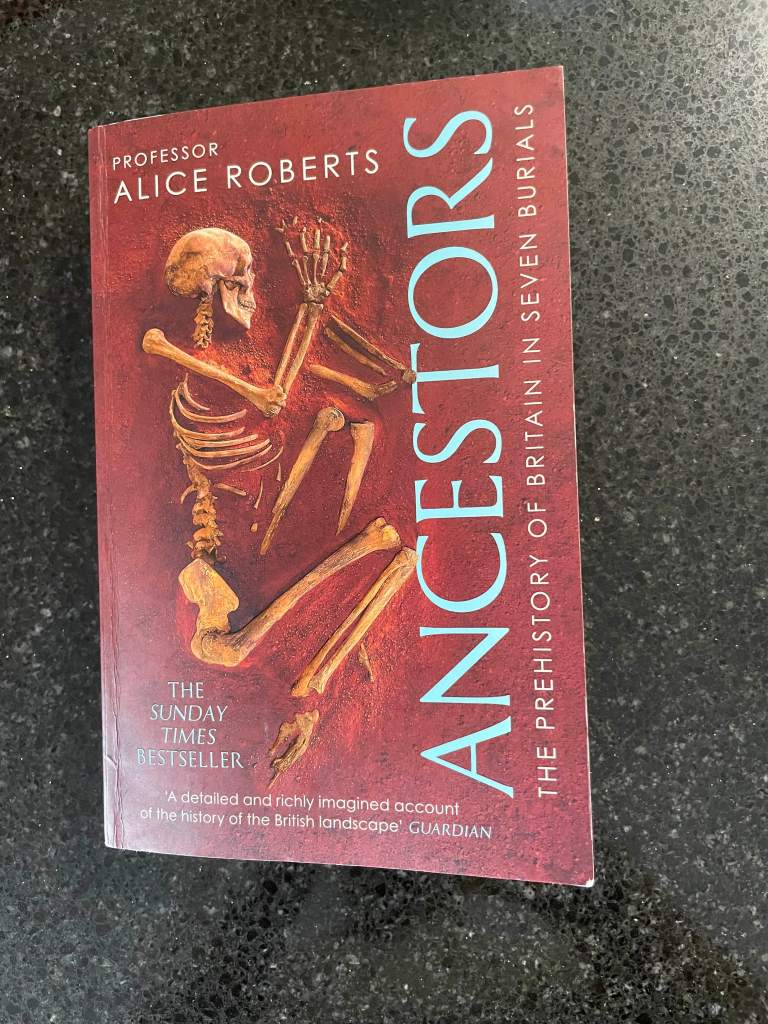

This is an excerpt from a book ‘ANCESTORS’ written by Professor Alice Roberts, first published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2021.

Professor Alice Roberts is an academic, author and broadcaster – specialising in anatomy and biological anthropology. She has presented over a hundred television programmes, on biology, archaeology and history, including landmark BBC series such as The Incredible Human Journey, Origins of Us and Digging for Britain. She also presents Britain’s Most Historic Towns on Channel 4.

At the time of adding this post to my blog, Alice has written ten popular science books, most of which we have in the library. In ‘ANCESTORS’ Professor Alice Roberts continues to explore the intersection between archaeology and genetics. I highly recommend reading this book and any others she has written.

The excerpt that is this blog posting is the last paragraph of the Prologue and the last ten paragraphs of the Postscript: Those Who Went Before.

“ This book is also about belonging; about walking in ancient places, in the footsteps of the ancestors. It’s about reaching back in time, to find ourselves, and our place in the world.

All of this effort to understand the past better is about understanding ourselves, as well. Humans are, I think, uniquely aware of our own mortality, the brevity of our lives and the context of those lives. We are just the latest human beings to occupy this landscape – it doesn’t belong to us in any way other than it forms part of our own story. And yet we can feel connected to a place by thinking about all those who have walked here before us.

Some people can get obsessed by ancestry, by trying to establish links with long-dead relatives. The lineages that always seem to cause the most excitement are those suggesting links to royalty. Sometimes those ancestral links are used to try to establish claims to territory. That can never really work as you have too many genetic ancestors to really make sense of such inheritance, if you go back more than a handful of generations. The geneticist and writer Adam Rutherford has written reams on how futile and spurious such lineage quests are. The doubling of ancestors at each generation means that, statistically speaking, you should have had over 2 trillion ancestors a thousand years ago – clearly several orders of magnitude more than the number of people who were alive on the planet at the time – and even today. What this means is that each thousand-year-old ancestor in your family tree appears many times, in different positions – the tree folds in on itself. And it also collapses into everyone else’s family trees as well. Any two Europeans, for instance, are likely to find a common ancestor popping up in both their family trees going back just a few centuries ago. A thousand years ago, they are likely to have many common ancestors. And those Europeans, a millennium ago, are likely either to be the ancestors of most Europeans today – or none of them. That is the fate of lineages – they either die out or spread like wildfire, down through the generations. People love to find out they are related to Charlemagne, or have Viking ancestry. But if you’re of broadly European descent – you will have. You don’t need a test to prove it. As Adam Rutherford puts it, “The truth is that we all a bit of everything, and we come from all over. If you’re white, you’re a bit Viking. And a bit Celt. And a bit Anglo-Saxon. And a bit Charlemagne.” And the further back you go in your family tree, the more globally interconnected it becomes. From a purely genetic point of view, though, there is a complication. The DNA of each of your distant ancestors is not just diluted, generation by generation – it can completely disappear from your genome. This is just a quirk of how DNA is shuffled and sorted into eggs and sperm. So there are members of your family tree way back, from whom you have no DNA at all. It’s been lost in time. Are they any less your ancestors?

Tracing ancestry using DNA turns out to be very useful for reconstructing ancient population history – looking at mobility and migration in the past, as we hope to do with the Thousand Ancient Genomes project. But it is much less informative and interesting from a personal, individual point of view – other than providing you with a picture of deep interconnectedness with everyone else. The genetic changes through which we glimpse those past migrations have very little. In fact, to do with identity.

As for ancestors to back up modern political claims – to power or territory – that’s clearly wrong-headed and futile too. I think we can feel a real sense of connection with individuals in the past – learning about their lives and understanding more about them – without needing a genetic connection to them. You can feel a sense of connection that is about common humanity – human experience.

If we try to connect with the past through individuals we believe to be our own ancestors in anything more than a very generic sense, it quickly gets overwhelming. There’s a paradoxical situation: when we go back through centuries, millennia, we accumulate thousands and thousands of ancestors – too many to feel any real connection to, too dispersed across the world to feel that we have roots in just one place; and of course the paradox also that, among those ancestors who exist in our real family trees, many left no genetic trace in us today. They are our ancestors on paper, but not in our genes.

The word ‘ancestor’, in fact, does not enshrine an idea of descent – although we use it that way legally, technically, biologically. The word itself is a descendant of a Latin word, via Old French, that is also extant in English, if less widely used: antecessor. It comes from ante, before, and cedere, to go – so it literally means ‘one who went before’.

Don’t try to possess these ancestors, then. Look at their lives, try to understand their societies and their cultures, find a new perspective on your own culture and sense of self through this exercise – but do not claim them for your own.

Instead, I feel connections through that human experience of being in a landscape – walking along the cliffs of Ronaldsay and imagining the early farmers there creating the chambered tomb; standing on the top of Winklebury Hill and imagining what it must have been like to have lived around there in the Iron Age; walking along the Gower coast and thinking about the people who lived and died there in the Ice Age.

I think we can explore those connections with landscape and discover a sense of belonging – a sense of place, of home – by examining the past in this way, by capturing moments in the life of one ancestor at a time. Especially those we see so clearly, in their time-capsule burials. We can imagine that other person’s life and connect with them. Walking in the footsteps of someone long gone, seeing a version of a view they once saw, experiencing the landscape they inhabited – that’s an incredible connection to the past.

And the past belongs to everyone. “

Leave a comment