The name Letitia derives from its Latin counterpart Laetitia, which directly translates to joy in English. With its roots in the ancient Latin language, Letitia has a rich historical background. In ancient Roman mythology, Laetitia was the goddess of celebration and mirth, known for her cheerful and lively nature. The name Letitia gained popularity during the Renaissance period.

Letitia Swan (1856-1943) was the second child and eldest daughter of Bessie (Cassidy)(Cain) Swan (1829-1869) and William Swan (1819-1895), her second husband.

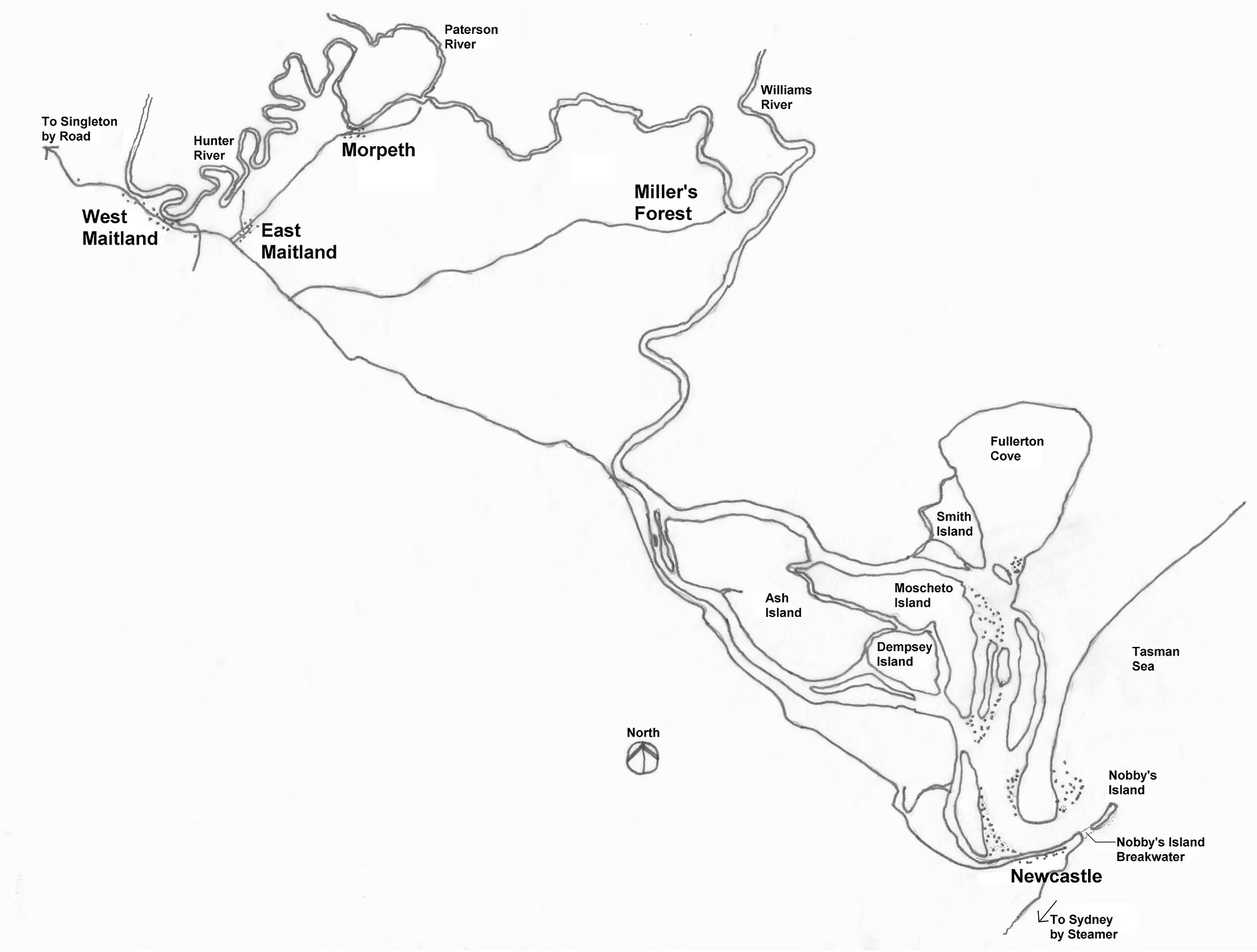

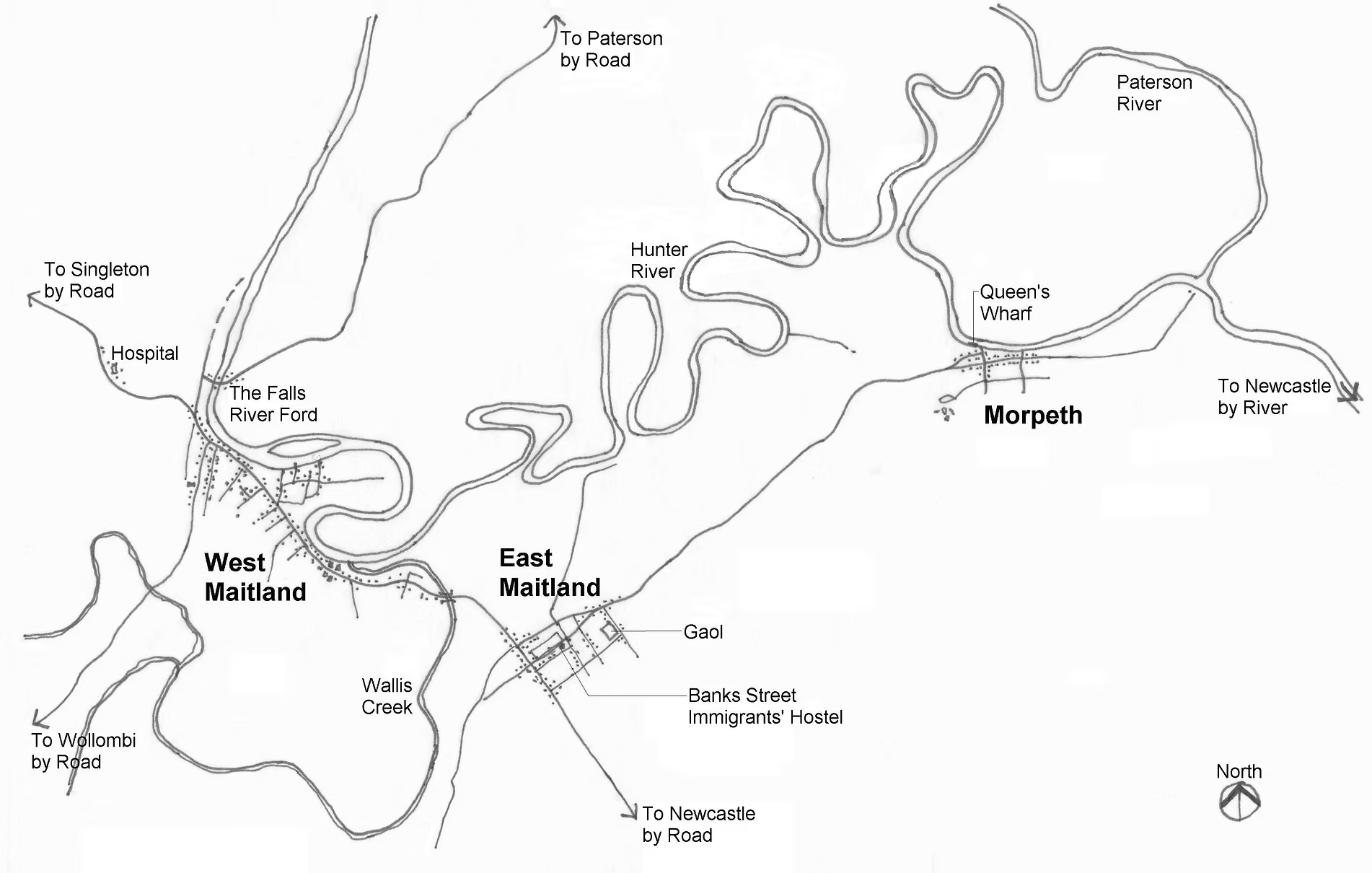

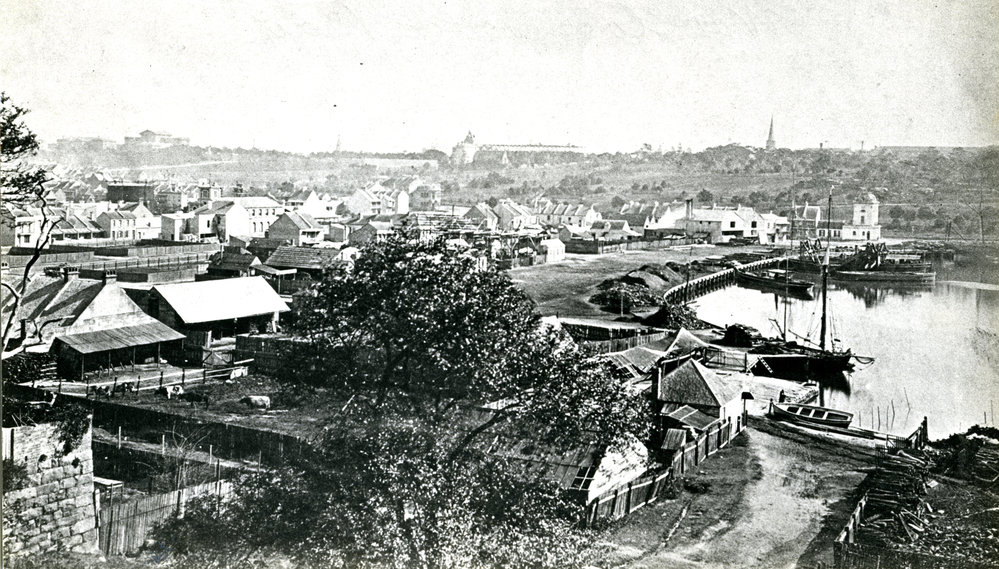

Letitia was born in the township of West Maitland on the 26th of March 1856, an important trade centre and farming hub in the Hunter Valley, more than 170kms from Sydney and 25kms west of Newcastle. The neighbouring flat river lands, the Wallis Plains, had been utilised for timber felling and farming from as early as 1816 when a penal settlement was built near what is now Newcastle. The Hunter River enabled shipping as far inland as Morpeth and goods were transferred by smaller boats to Maitland. Morpeth became the major port in the area and most commerce centred around it.

Letitia was the first of her family to be born outside Sydney. Her older brother, William Swan Jnr. (1854-1887), was born in Newtown early in 1854.

The Swan family moved back to Sydney sometime before 1862, now enlarged by two more children, Thomas Cormick Swan (1858-1943) and Louisa Alice Swan (1860-1941). They lived around the western edges of Goulburn Street, near Dixon Street and the Dixon Wharf. This is also where Letitia’s half-sister, Mary Ann Cain (1845-1886) and her husband, William Hurwood (1838-1916) had settled in Sydney after marrying in West Maitland. Much of our understanding of people’s lives during this period comes from Church records, newspapers, directories and colonies’ Police Gazettes. In the NSW Police Gazette of January 1st, 1868, it was reported that a warrant had been issued for the arrest of a William Jones, who was charged with assaulting the eleven-year-old Letitia Swan with intent to commit a rape.

Almost two years later, on the 30th of December 1869, Letitia’s mother, Bessie died, leaving Letitia as the eldest daughter in the family which now numbered six children, the youngest a two-year-old Elizabeth Swan. Two half-sisters, Mary Ann Cain (1845-1886) & Sarah Eliza Cain (1849-1916), the daughters of Bessie Cassidy and her first husband, Thomas Cain and their families lived close by and it has always appeared that they were a close-knit extended family.

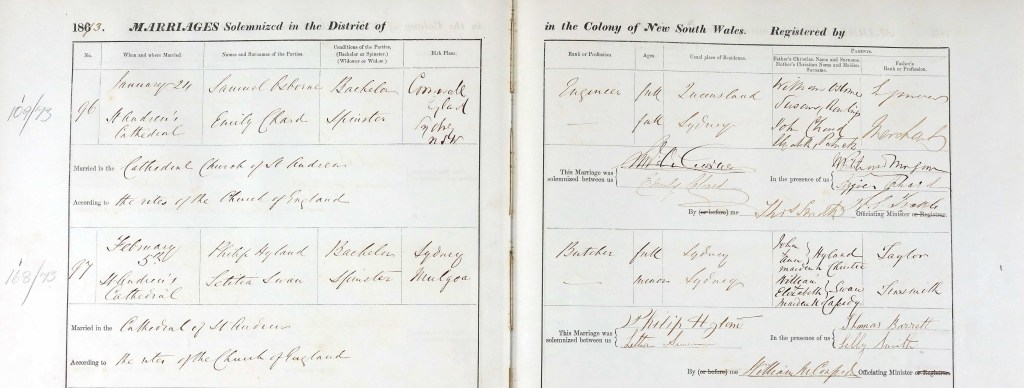

On the 5th of February 1873, Letitia, now sixteen, married a butcher, Philip Hyland (1849-1880) at the Cathedral of St. Andrews on George Street, next door to the Sydney Town Hall.

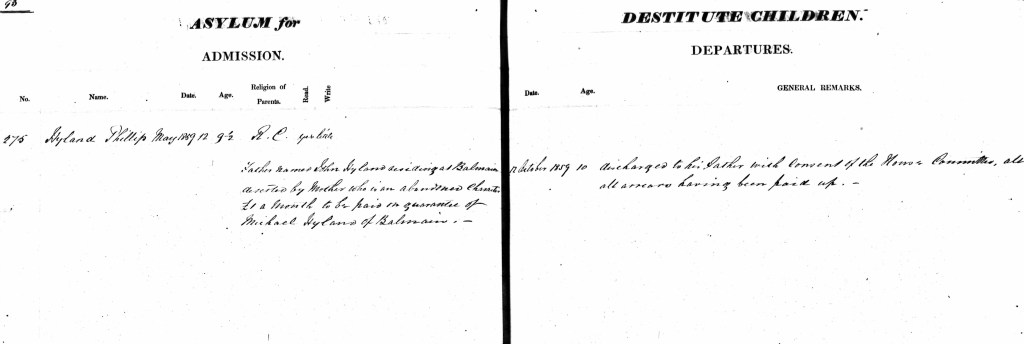

Philip Hyland had a very tough early life. He was born in Sydney in 1849, the son of John Hyland, a tailor, and Ann Christie. The notes attached to his formalised admission and departure in and out of the Randwick Asylum for Destitute Children outline a very troubled and possibly unwanted childhood.

Admission: Hyland Phillip; 12 May 1859; Age: 9&1/2; parents are Roman Catholic; can read and write a little.

Father named John Hyland residing at Balmain deserted by Mother who is an abandoned character. £1 a month to be paid in guarantee of Michael Hyland of Balmain.

Departure: 12 October 1859 Age 10.

Discharged to his Father with consent of the House Committee, after all arrears having been paid up.

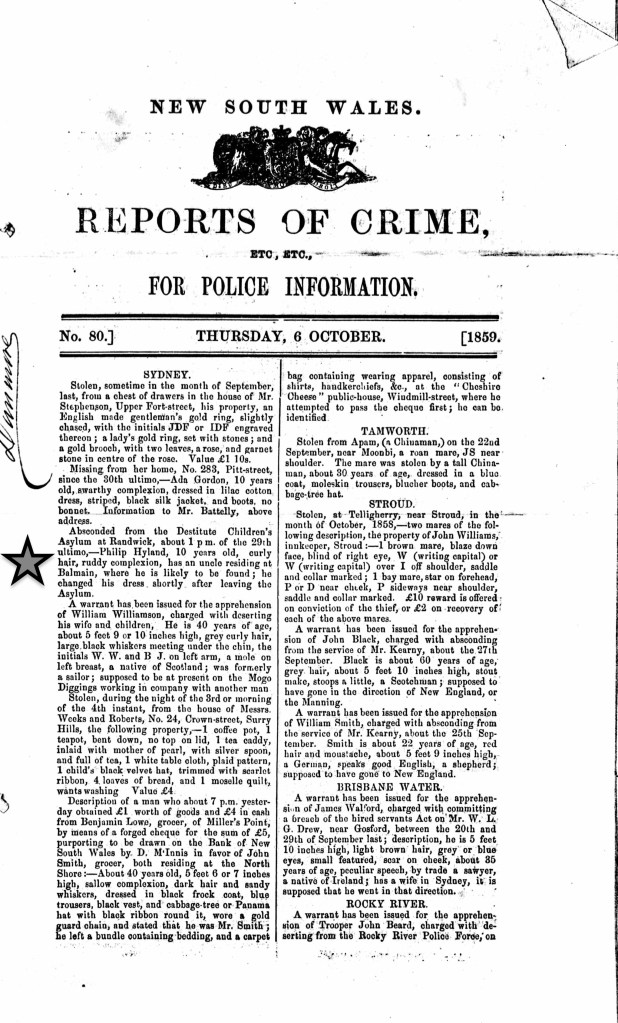

The NSW Police Gazette issued on Thursday, 6 October 1859 reports that Philip Hyland has absconded from the Randwick Asylum for Destitute Children on the 29th of September and that he is likely to be found with his uncle who lives in Balmain.

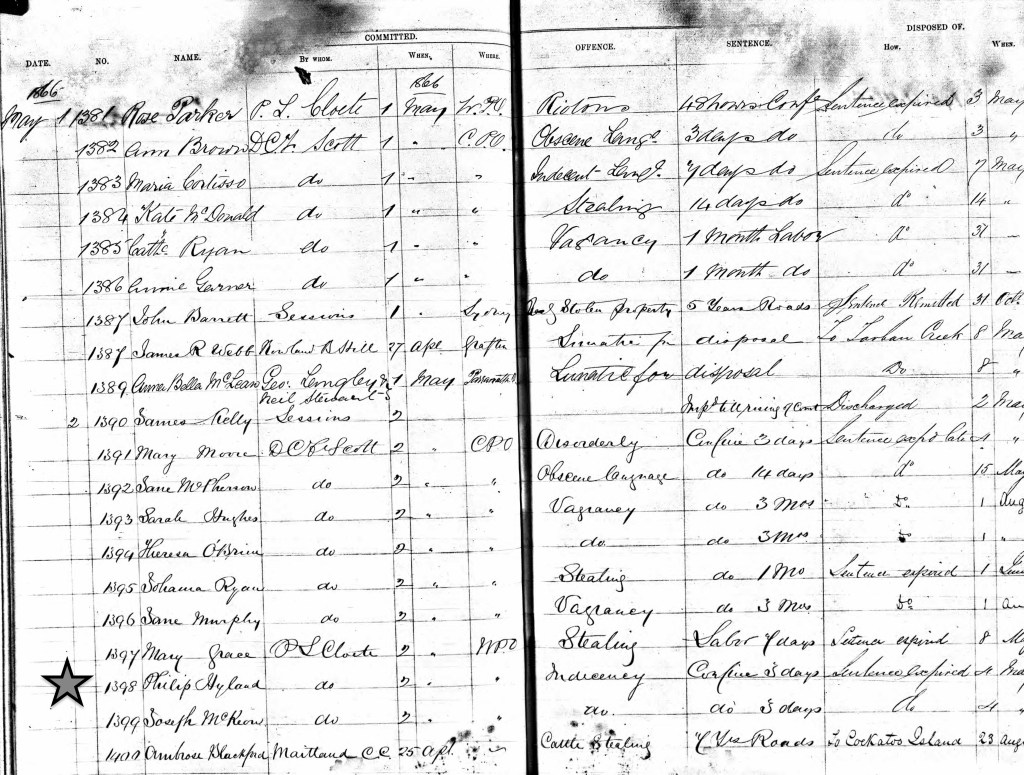

We next find that Philip has been apprehended and admitted to the Darlinghurst Gaol for the offence of “Indecency” on the 1st May 1866 and sentenced to Confinement for 3 days. Yes, the imagination does run riot at the thought of the fifteen-year-old Philip Hyland being in the major Sydney gaol for a few days on an indecency charge, however the nature of life in a former penal colony which was also the major port of entry was less than stellar.

In addition to the Marriage Certificate of Philip and Letitia there is good documentation available of the colony’s births and deaths. Their first child, a son, William John Hyland (1873-1875), was born on the 11th of November 1873 and did not live long. Tragically, infant deaths are found to be an integral part of most families during this period of the 19th century, both in the northern hemisphere and in the southern colonies. Letitia was only a couple of months pregnant with her second child when the first, William John Hyland, only 13-months -old, died in Sydney. The second child, also a son, is named after his father and Philip Hyland Jnr. (1875-1880) was born at the end of August 1875.

The third and the fourth children born to Letitia and Philip Hyland were also both boys – Henry Hayden Hyland (1877-1880) and Francis Hyland (1879-1880). Francis lived less than a year, dying on the 27th of January 1880.

Only one month gone in 1880 but worse was to come.

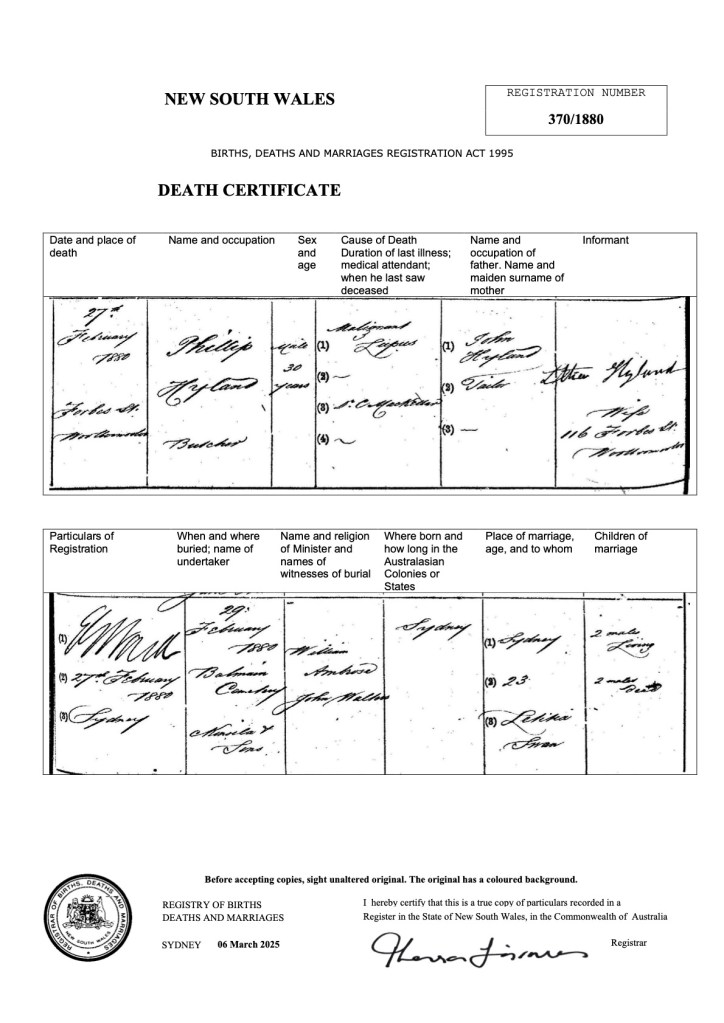

1880 was a leap year. It proved to be an absolutely terrible year for Letitia and her family. On 27th of February 1880, only a month after the death of her fourth son, Francis, her husband, Philip Hyland died of “malignant lupus”. He was only 30 years of age and was buried at the Balmain cemetery on the 29th. Lupus is a disease where the immune system attacks the normal cells, damaging organs and tissue throughout the body. Family members maintained that Phillip Hyland had been kicked in the head by an animal about to be butchered, a cow perhaps, and this was the root cause of his autoimmune system collapse which led to lupus. The history of lupus can be traced back to the 12th century when the term “lupus” was first used in medicine. However, the disease’s systemic nature wasn’t recognised until the late 19th century. Lupus is Latin for “wolf”: the disease was so named in the 13th century as the facial rash that occurs was thought to appear like a wolf’s bite.

February 1880 was heartbreaking, but worse was to come.

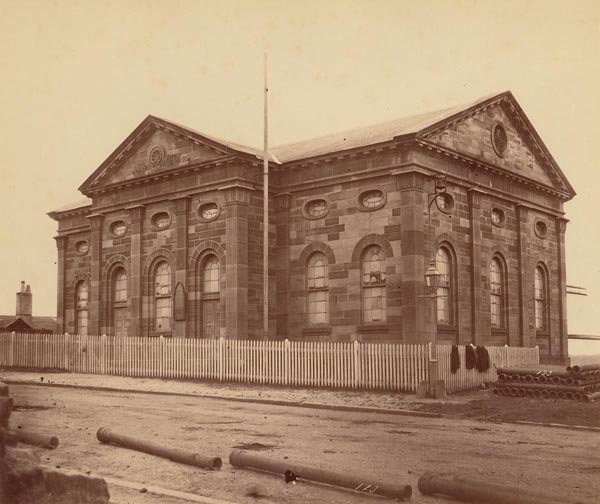

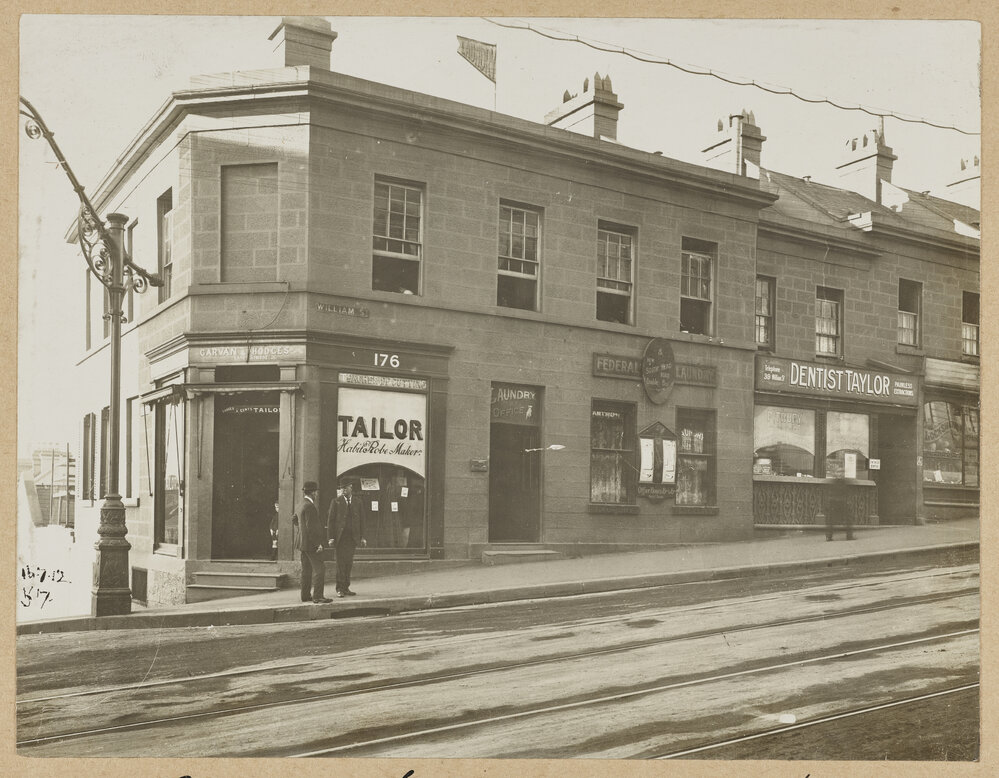

Philip’s death certificate records that Letitia and her family were living at 116 Forbes Street in Woolloomooloo. The address “Forbes Street” is also given as the place that Philip Hyland had been operating as a butcher. They were only a few blocks away from where William Swan Snr. was living at that time. After Philip’s death Letitia worked as a housekeeper at a nearby hotel, the United States Hotel, on the corner of William and Riley Streets. Working as a housekeeper enabled Letitia to have her two young sons with her, which probably would not have been possible if she pursued the butcher business. We do know that there was no such thing as Government relief or benefits available, only personal savings or family members’ assistance. Despite grief, people just had to resume life, provide shelter and food; in essence, just “get on” with the daily grind.

The daily grind in 1880 was to sorely test Letitia.

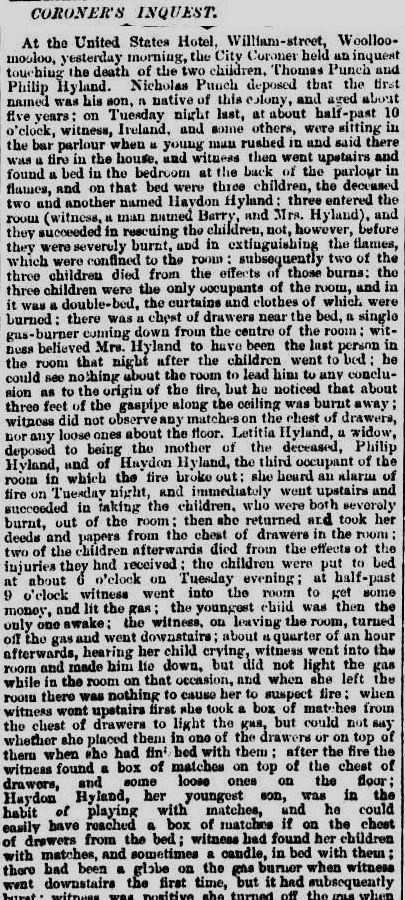

On the 8th of June 1880 Letitia was enjoying a social evening in the parlour of the United States Hotel on William Street, Woolloomooloo, just around the corner from her dwelling on Forbes Street. She had been attending a concert and was in the company of Nicholas Punch, the publican of the hotel and a Mr. Barry, whose older sister, Annie Maria was married to Nicholas Punch. Annie Maria and Letitia were the same age and both had experienced the loss of children at a young age.

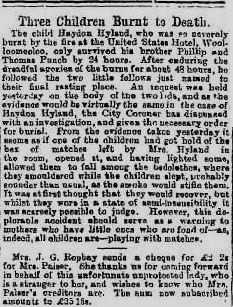

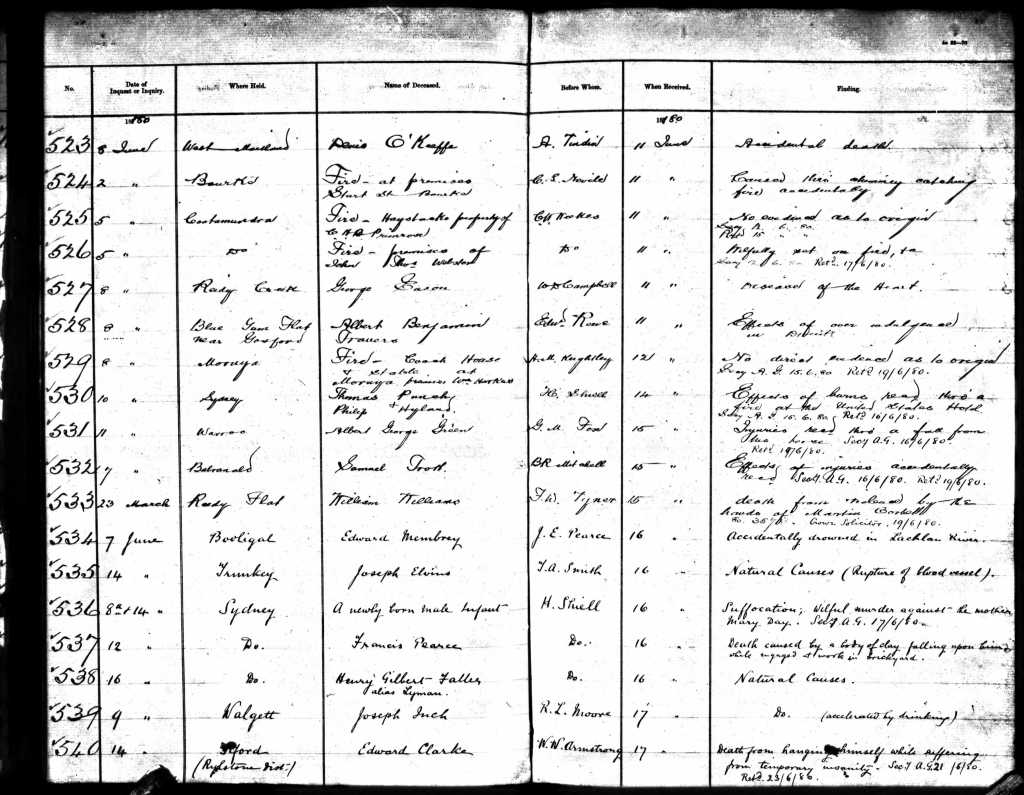

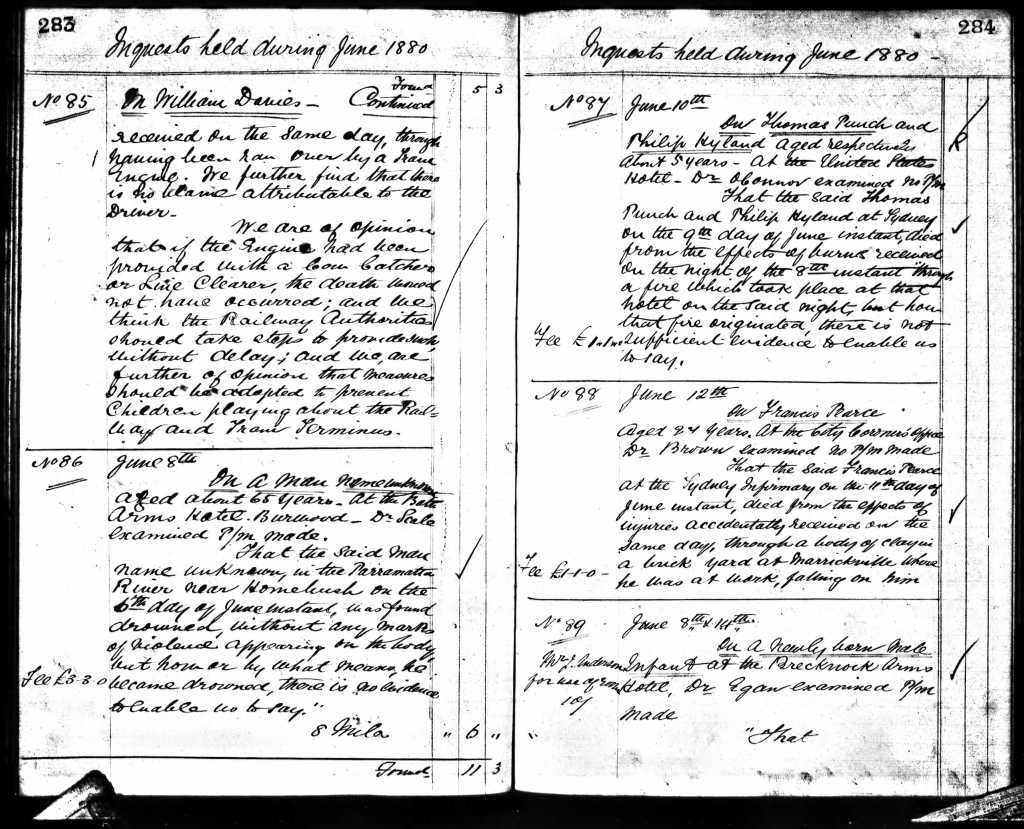

Letitia’s two children, Henry Heyden (3 years old) and Philip (4 years old) were asleep in in a bedroom upstairs and behind the parlour along with the Punch’s son, Thomas Punch (5 years old). At about 10:30pm a young man rushed into the bar parlour and said there was a fire in the house. The bedroom shared by the three sleeping boys was alight with flame and over the next two days all three died from the effects of burns they received.

You’ll see coroner’s report, an inquest and newspaper articles that do nothing to diminish this tragedy. Letitia must have been devastated, a heart-broken grieving mother who in the space of six months had lost her three sons and her husband.

Life goes on.

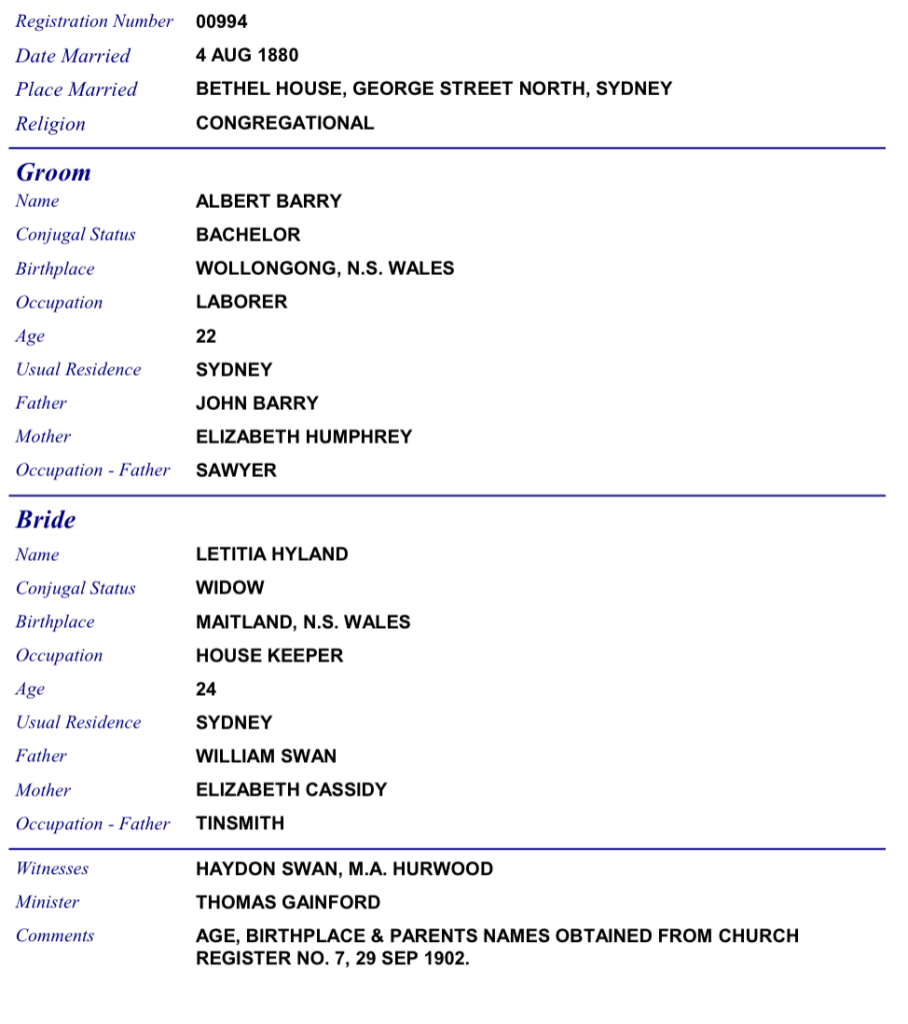

On the 24th of August 1880; yes, we are still in THAT year; Letitia marries a lad from Wollongong, Albert Barry. I assume that this is the same Mr. Barry who was at the United States Hotel on that horrific Tuesday evening when the three little boys met a their most untimely end. Letitia and Albert were married at the non-denominational Mariners Church at the Rocks, 98 George Street. The witnesses were Letitia’s younger brother, Haydon Swan and her half-sister Mary Anne Hurwood.

Letitia had five children in her marriage to Albert Barry and initially it seemed that her wretched luck would continue as the first two of these children, both boys, Albert Barry (1881-1884) and Philip Edward Barry (1882-1884) died at a very young age. Two daughters preceded another son and all three of them married and had children. Perhaps now Letitia’s joyous “name” could come into fruition. Certainly, this time in her life appeared to be happier and more exuberant than her first 30 years.

I will note here that Letitia Swan, who lived well into her 80’s was known as Grandma Barry by her grandchildren, the daughters and sons of Elizabeth (Barry) Tooker (1884-1940), Letitia (Barry) Sears (1887-1960) and Albert Willian Barry (1891-1958). There are wonderful memories and notes about the family that have been kept by these descendants. They provide some delightful and interesting “colour” to the lives of the Barry Family, especially Letitia.

Letitia’s three children were known as “Cooge” (Elizabeth (Barry) Tooker); “Bubs” (Letitia (Barry) Sears) and “Son” (Albert William Barry).

“Grandma Barry had “ripe corn coloured” hair or otherwise was a “strawberry blonde”. She loved the theatre – and play acting, which she and her sisters and brother did all the time when they were growing up. She recited Shakespeare until well into her 70’s and, as well, loved singing from the operas. “I remember her reciting Shakespeare and singing. It really was something” said Bess Enid Tooker (1920-2008).

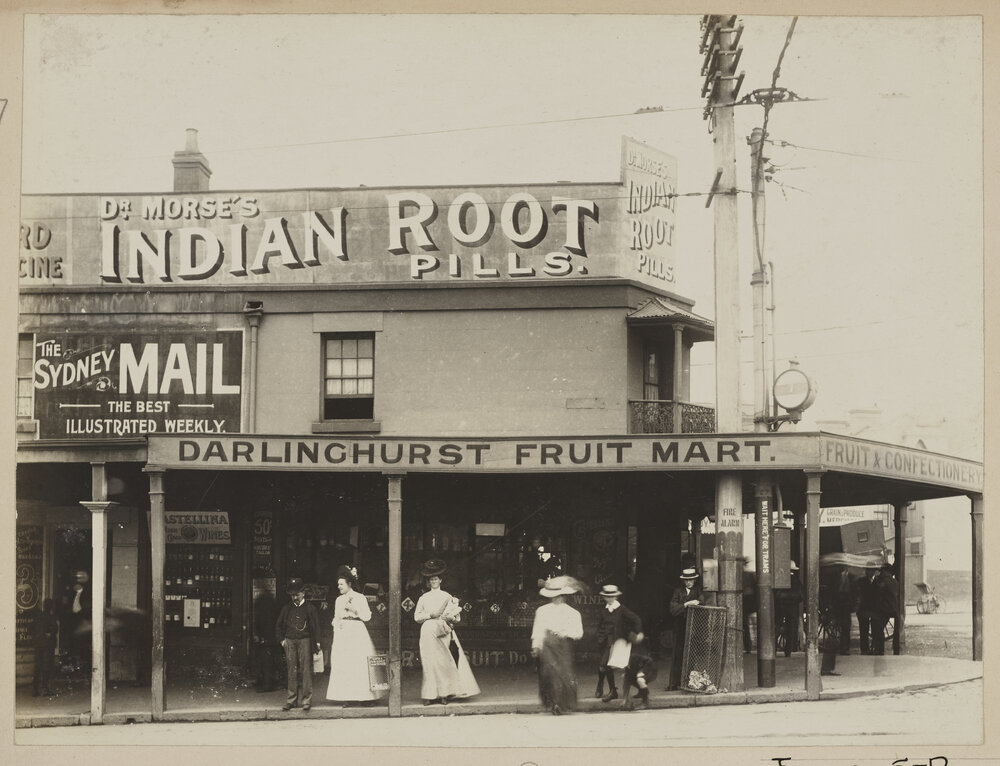

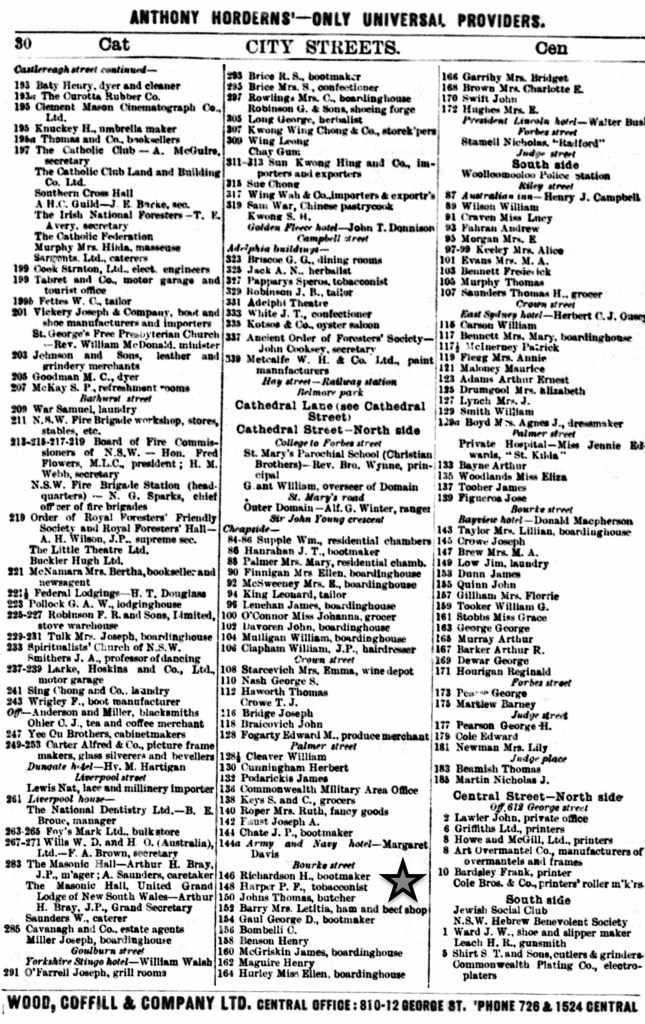

Albert Barry possessed some very good business skills and had some experience working as a butcher primarily in Parkes, one of the towns besides Bellambi that his family resided in during the late 1800’s. Letitia knew the beef and ham business and over the next 25 years, working together they opened retail and wholesale outlets in and around the inner eastern city suburbs of Woolloomooloo and Darlinghurst trading as Barry’s Butcher Shop. They stayed in this area with business addresses on Forbes Street, Woolloomooloo Street, Bourke Street and Dowling Street recorded in Sand’s Directories from the 1880’s through to the early 1900’s.

From the family notes: “In addition to the butchering shop in Forbes Street, they had two shops in Dowling Street, which were 3 stories high with a big basement where the men fed. The “boss” had to feed, & board, single men. They supplied ships, with one shop always spoken of as the “Bay” shop.

They also kept trotters – Brownie, Ginger and Blue St…(?).

The Swans were Church of England and the Punch family Roman Catholic. Grandpa Barry changed his religion very late in life and made bequests to St Mary’s Cathedral.

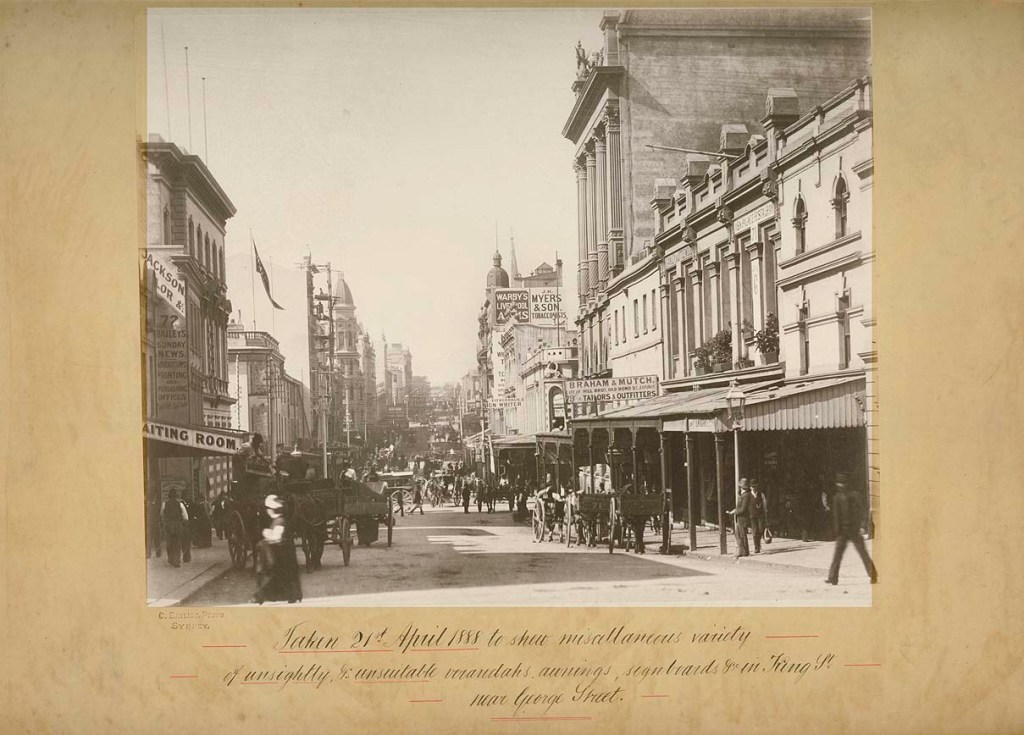

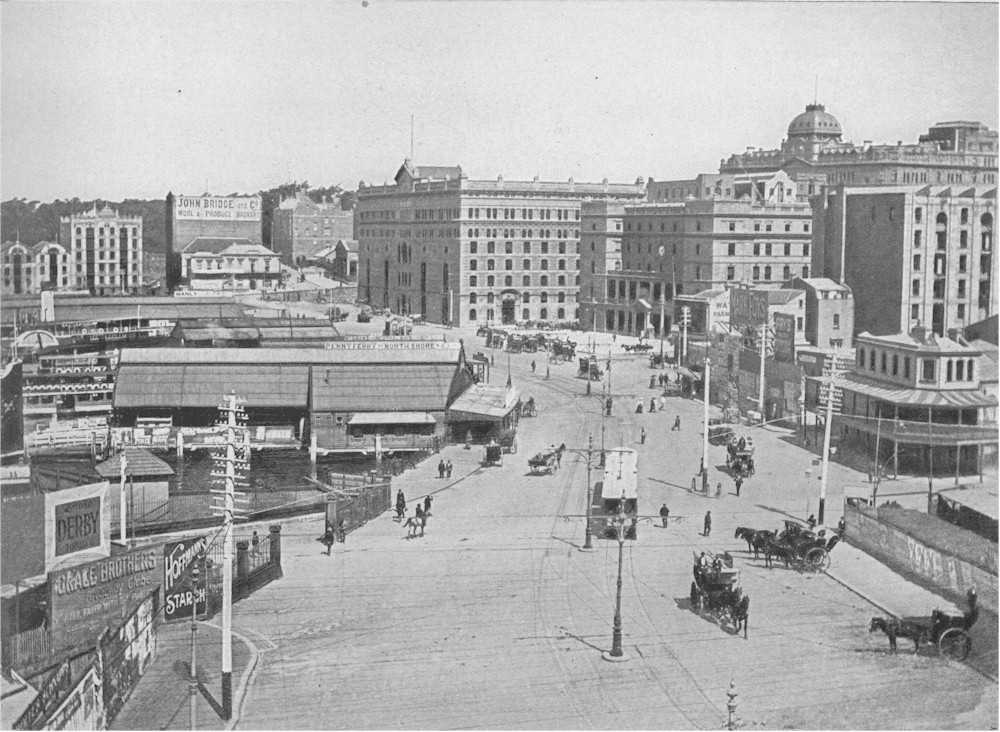

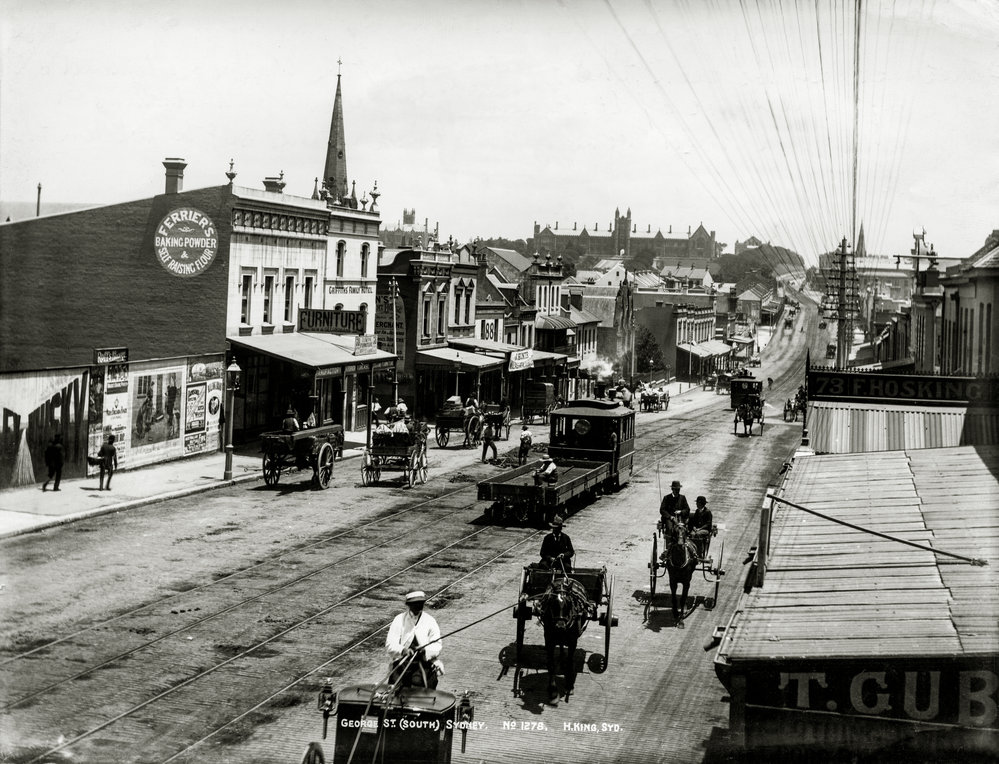

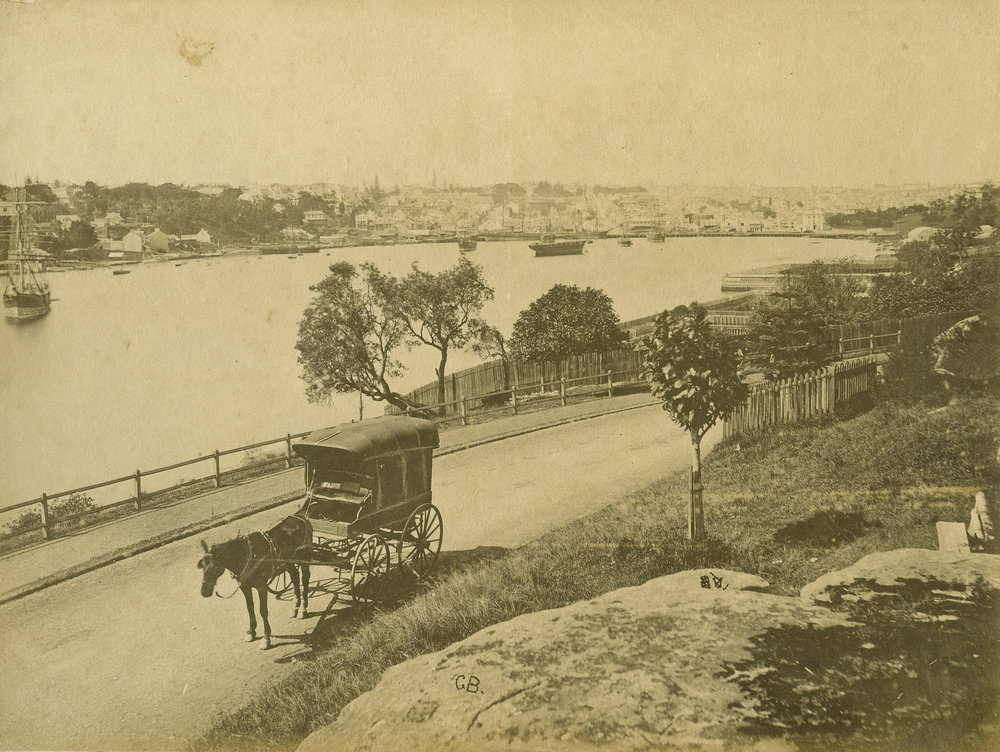

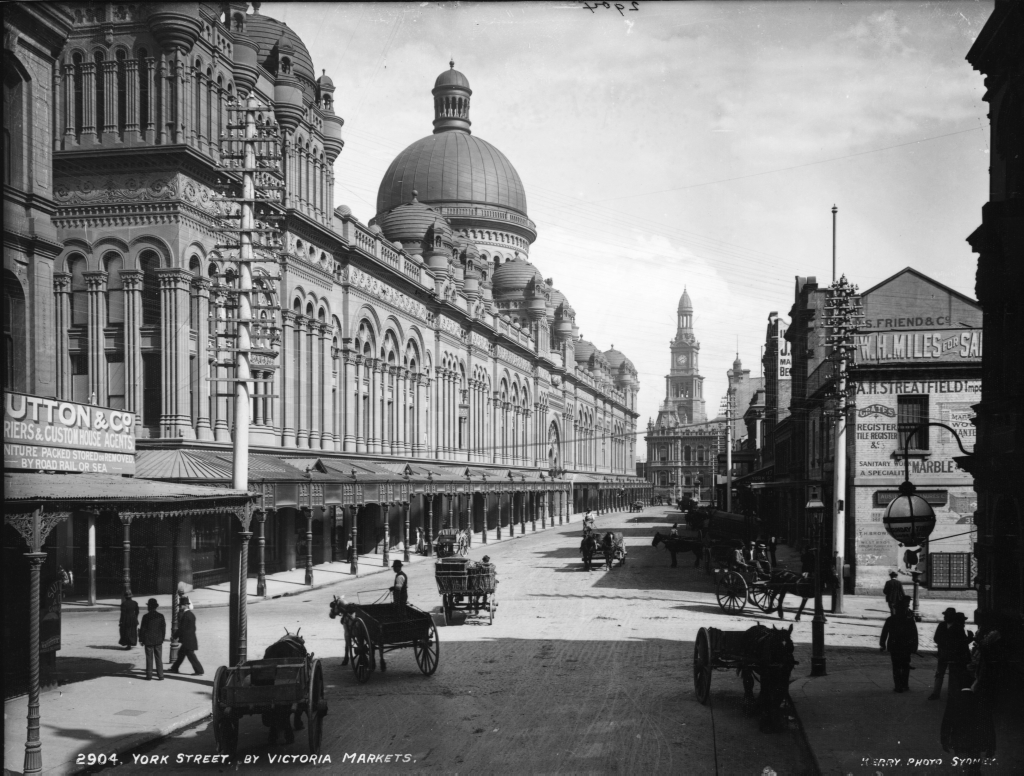

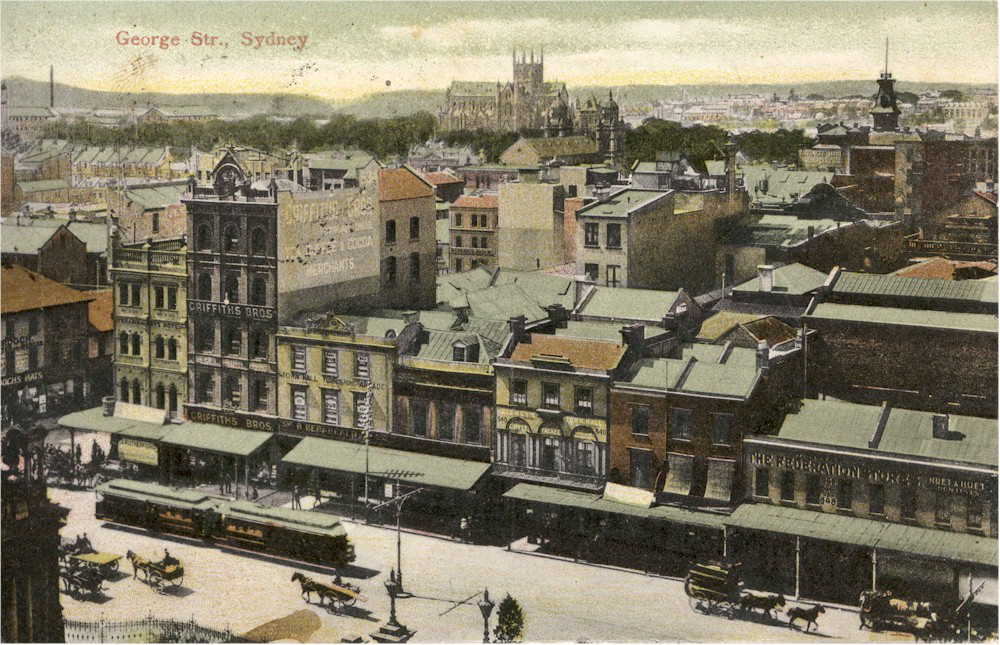

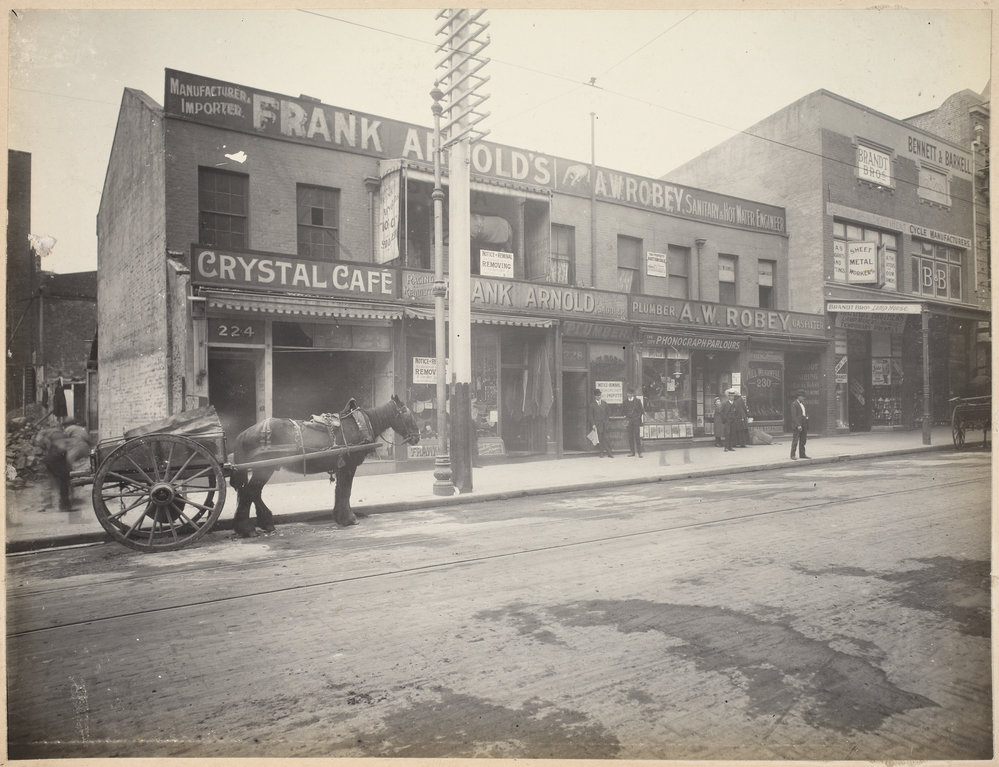

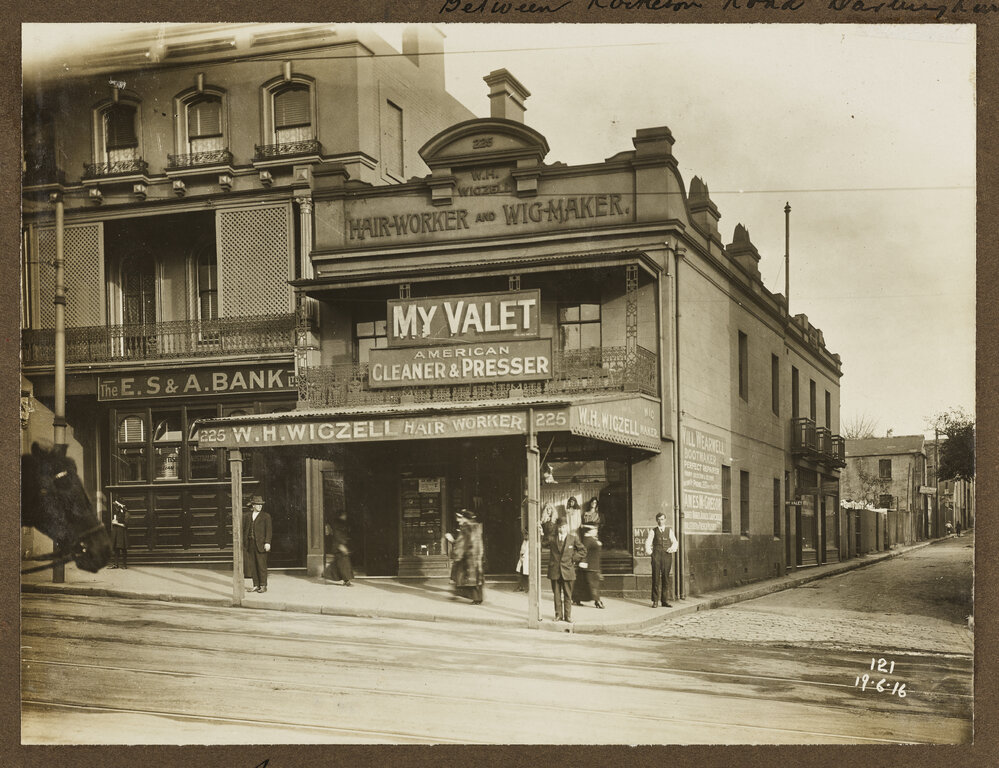

Various street photographs in the late 1800’s of inner Sydney, Darlinghurst and Woolloomooloo, the parts of the city that the Barry’s called home.

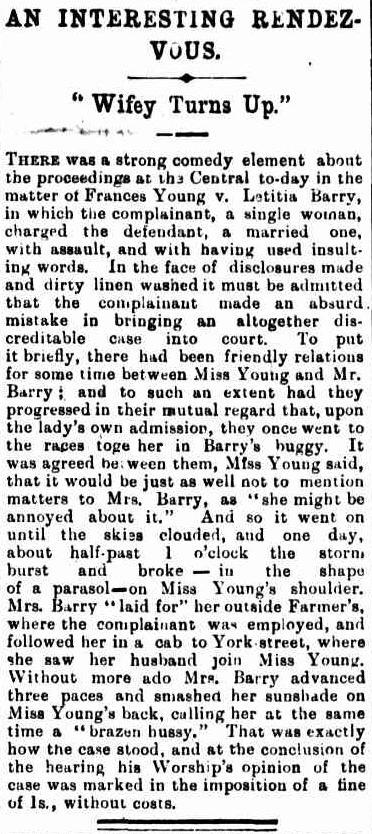

I don’t want to make light of any infidelity, however a most interesting newspaper story appeared in the Australian Star on Thursday the 15th of October 1891:

The reporter says it all, calling it “an absurd mistake in bringing an altogether discreditable case into court”. The judge obviously knew where righteousness lay in fining Letitia one shilling without costs. It is also interesting to note that their fifth child, Albert William Barry (1891-1958) was born only two months before this incident.

Some more city scenes; mostly from the early 1900’s show the expansion and growth of Sydney.

We will look at the more specific details of Sydney’s growth in a few pages but by the turn of the century Australia now a Federal Government, most sewage and water problems had been sorted out in Sydney and horsemen throughout the colonies were assisting England in the First & Second Boer War.

And Barry’s Butcher Shops were thriving!

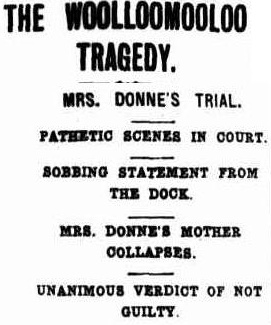

The newspapers had a particularly salacious story to exploit in August 1913; a story that put the lens firmly on Barry’s Butcher Shop

The Manning River Times on 9th August, 1913 reported the following:

“Shortly before noon to-day, William Donne, aged 35 years, was shot dead by his wife at Barry’s butcher’s shop, 81 Dowling-street, Woolloomooloo. One shot was fired, and Donne fell in front of his door on the footpath, ‘ and died almost immediately. Mrs. Donne, who is young and ‘attractive, was taken inside, and the employees telephoned for the police. When arrested, Mrs. Donne volunteered the information’ that- she had shot her ‘ husband, but on being warned, relapsed into silence. She was brought before the Central Court and remanded to August 14. Mrs. Donne fainted in the dock and was carried out by the police. The revolver when picked up had two soap cartridges, one discharged shell, and three full cartridges discharged between the soap cartridges. It looks as if Mrs. Donne meant to fire the blank cartridges, but by mistake fired a live cartridge.”

The story was an instant hit, the courthouse filled and overflowing, fodder for all newspapers who tried to outdo each other with sensational headlines complete with people fainting in court and in the end a verdict of not guilty!

On the 23rd of November 1913 Albert ‘Grandpa’ Barry died. He was two days short of his 53rd birthday and he and Letitia had enjoyed almost 35 years of marriage. The greater majority of his family were still alive, including his mother. A death notice was posted in the Sydney Morning Herald on the 24th November 1913:

BARRY – November 23, 1913, at his residence, 81 Dowling-street Woolloomooloo, Albert, beloved husband of Letitia Barry, aged 53 years.

Five days later there was another posting in the Sydney Morning Herald on the 29th November 1913:

Mrs. ALBERT BARRY and FAMILY desire to return their sincere THANKS to all kind friends and relations for their floral tributes, letters, telegrams and cards of sympathy, received in their recent sad bereavement.

The Death Certificate was issued on the 24th of November and stated that Albert Barry’s death was from cirrhosis of the liver. He was noted as a Master Butcher and was buried in the Waverly Roman Catholic Cemetery. The informant for the Certificate and witness to the burial was his son, Albert William Barry.

It seems that Letitia continued in the business for a few more years, there is a listing for her in the 1915 Sands Directory at 152 Cathedral Street:

“Barry Mrs. Letitia, ham and beef shop”

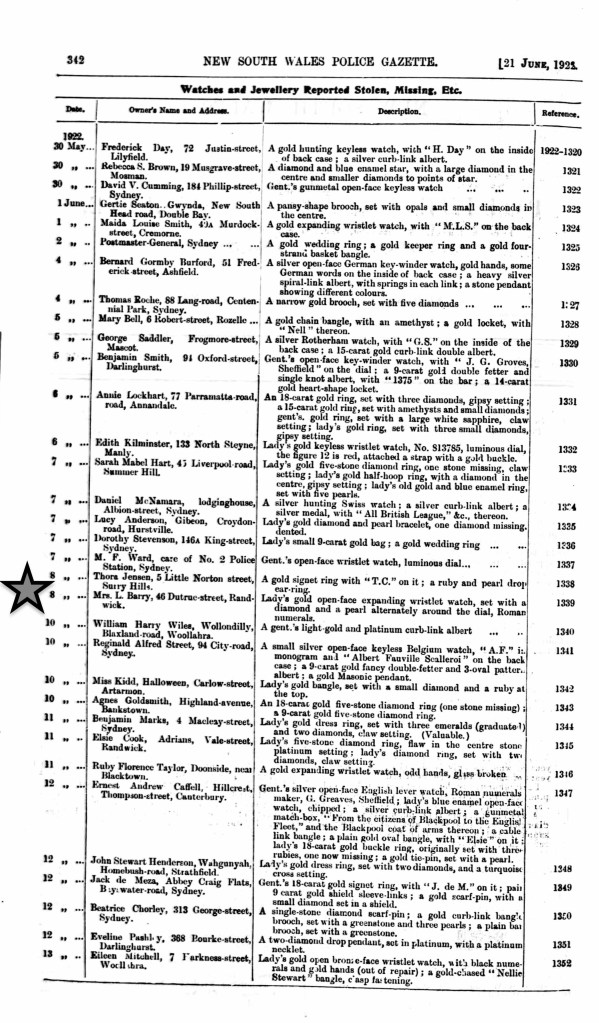

Cathedral Street was known some years earlier as Woolloomooloo Street and her shop would have been just near the intersection with Bourke Street. At this point Letitia is almost 60 years old and there is a dearth of information about her for the next 25 years. We can find a Mrs. L Barry living on Dutruc St Randwick in 1922; on St Marks Road Randwick from 1928 through 1931; and electoral rolls have a Letitia Barry at two addresses, 5 Piper Street and 213 Trafalgar Street, both in Annandale through the 1930’s. Randwick and Annandale are only a few kilometres from Woolloomooloo, part of the suburban growth that Sydney had been steadily experiencing since the 1860’s when Letitia and her family had settled back into inner Sydney after spending some years out in the Hunter and Maitland region.

Letitia has now retired, probably singing and enjoying time with her grandchildren. There is a mention in 1922 when the Police Gazette publishes a theft of her wristlet watch.

Letitia and Albert’s eldest daughter, Elizabeth (1885-1940) married Percy Sinclair Tooker (1882-1939) in Sydney in June 1903. They had seven children, five of whom were born before Albert’s death, so there was probably a lot of contact between Letitia, her children and her grandchildren.

During the second half of the 19th century Sydney was rapidly emerging as an international city, a far cry from it’s colonial convict past. This meant that for Letitia, as with all inhabitants of Sydney, dramatic change.

Albert and Letitia had lived through and seen a lot of change during their 33-year marriage in the middle of Sydney as they developed their retail butcher business. Possibly the greatest change was Australia transitioning from six colonies into a Federation of states, a process that had begun back in the 1840’s and took fifty years to come into fruition. The discovery of gold in both New South Wales and Victoria in the 1850’s resulted in significant growth for the two major cities of Sydney and Melbourne. The population of Sydney grew from 60,000 in 1850 to 400,000 in 1890. We have noted in Part 1 of the “Sydney Swans” the severe problems that Sydney faced during this period of growth regarding water supply and sewage disposal.

To facilitate Sydney’s growth, suburbs of tightly packed terrace houses were built. I posted many photographs of these earlier in the blog along with street scenes. These houses, with their balconies and decorative cast-iron railings, are now Sydney’s most attractive heritage from the past. There was more expansion when the first railway, from Sydney to Parramatta, began as early as 1855.

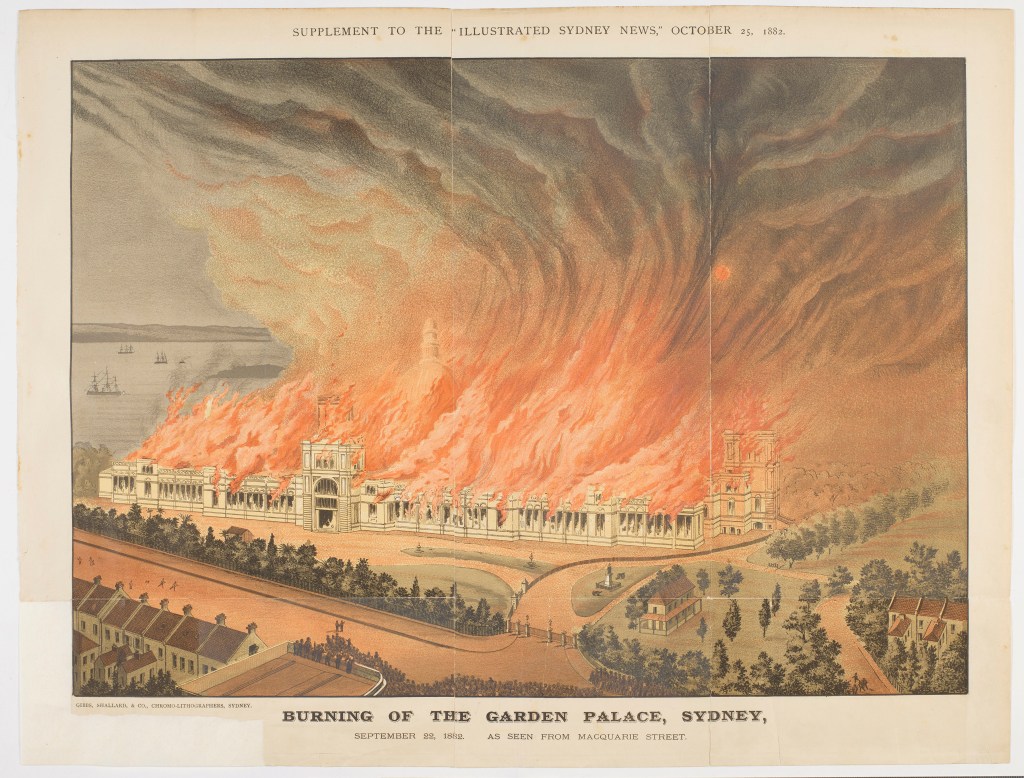

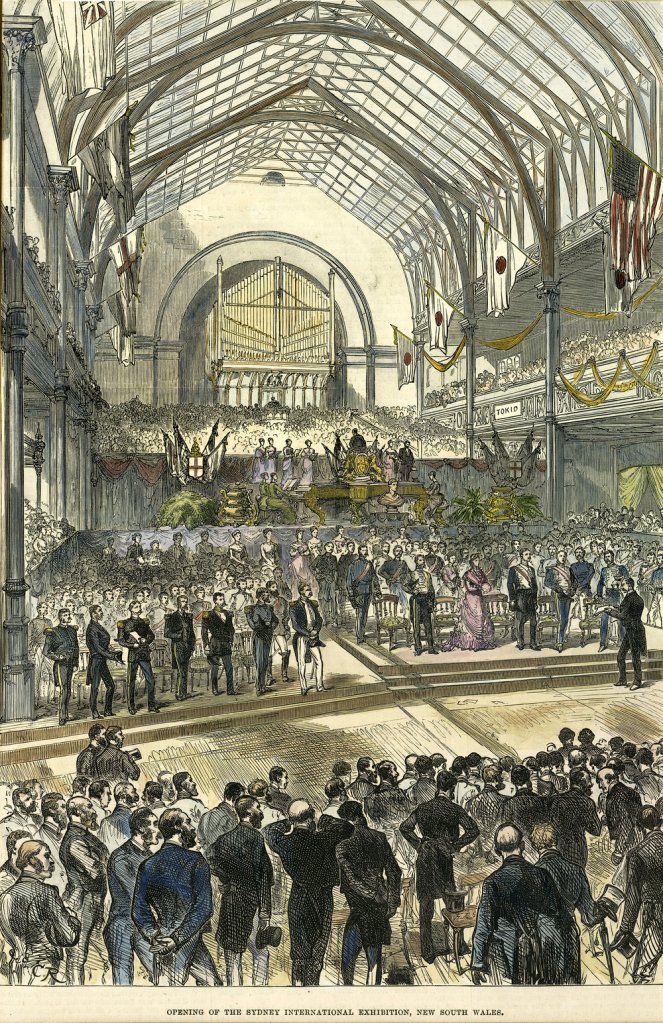

Both Sydney and Melbourne were in fierce competition to attract international business and recognition, along with the investment that flowed from Europe in general and Britain in particular. In 1879 Sydney secured “The Sydney International Exhibition” which showcased the colonial capital to the world. This glamorous presentation was modelled along the great exhibitions of Europe and aimed to promote commerce and industry, along with art, science and education. A site of 35 acres on the high ground of the Inner Domain along Macquarie Street was chosen for the exhibition. A large building, the Garden Palace, was constructed to house the exhibition. It was completed in eight months, largely due to the importation from England of electric lighting which enabled construction to be almost continuous. Some exhibits from this event were kept, constituting the original collection of the new “Technological, Industrial and Sanitary Museum of New South Wales” which is today’s Powerhouse Museum. The building was completely destroyed by fire in 1882.

The push for Federation was gaining momentum during the 1880’s particularly as increased activities of foreign powers in the Pacific made the colonies realise that a united front to the British Government would result in a safer and stronger strategy. Germany had designs on New Guinea (which Queensland promptly annexed) and there was increased French activity on the New Hebrides together with plans to transport recidivists to New Caledonia. Further afield, conflicts in Sudan and South Africa resulted in colonial Australian soldiers being sent to “assist” Britain’s somewhat fragile grip on some parts of it’s Commonwealth. Australia’s involvement in 1885 for a few short months in Sudan was the first time Australian troops had fought in an imperial war.

In 1877 Australian nationalism and obvious yearning for federation was delivered a stirring promotion when a cricket team from Victoria and New South Wales defeated the visiting British side. A successful victory five years later, in August 1885 at the famous Lords Oval gave rise to the legend and adoption of the “Ashes” cricket tests between Australia and England. The love and associated strong support for all things sporting in Australia was becoming very noticeable as a divergent population fostered a broad range of egalitarian entertainment.

A financial collapse in the 1890s acted as a slight check to Sydney’s growth, but population doubled again by 1914 and reached the million mark soon after.

On January 1st, 1901, the Commonwealth of Australia was proclaimed and inauguration ceremonies held at Centennial Park in Sydney included the swearing in of the Governor General.

The next decade saw many milestones reached as Australia became a sovereign nation. Federal elections were held, Edmund Barton confirmed as the first Prime Minister, a Census was held in all states, the vote extended to all women but denied to Aboriginal people, the National capital site selected, Walter Burley Griffin won the international competition to design the federal capital, the Government issued stamps and bank notes.

The Boer War which was fought by Britain from 1899 to 1902 against two small Boer republics resulted in a victory for Britain and saw the involvement of about 16,000 Australian troops. Although initially supportive of this conflict, Australians became disenchanted with the war as it dragged on, especially as the toll on Boer citizens became known. The story of Breaker Morant, either in book or film format is part of Australian heroic legend. “Hutton – what’s in a name?” can be found somewhere in the blog which focuses on some different aspects of the Boer War and family history. Letitia (Swan) Barry was the aunt of Louisa May (Swan) Vacchini (1884-1948) whose husband Caleb Francis Vacchini (1870-1947) was a member of the NSW Mounted Horse who fought in the Boer War. Their son, Caleb Hutton Vacchini was so named in honour of the commanding officer of the Australian forces, General Hutton.

Sydney became the capital of the State of New South Wales, and the spread of bubonic plague in 1900 prompted the new state government to modernise the wharves and demolish inner-city slums. The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 saw more Sydney men volunteer for the armed forces than the Commonwealth authorities could process, and helped reduce unemployment in the city.

All these things and all of this progress would have been topics of conversation, interest and involvement to the majority of Sydney’s population. They all had an effect on “the economy” and were relative to bragging rights between Sydney and Melbourne. Temporarily overtaking Sydney in both size and importance, Melbourne became the financial centre of Australia, and it was the capital of the Commonwealth of Australia until the Federal Capital of Canberra was built in 1927 halfway between the two cities. By 1911 Sydney had once again become Australia’s largest city.

As we get closer to WWI, here is another gallery of housing in the city:

However, we now need to closely look at a most important issue, one that is almost unique to Sydney. This culture changing issue saw a convergence of sporting adulation, a year-round attraction for all people, worldwide recognition and the reluctant rejection of Victorian mores in favour of common sense.

This is a photograph of Bondi beach circa 1900. It was illegal to swim in daylight hours, it was illegal to swim naked.

The issue? Water sports, in particular swimming.

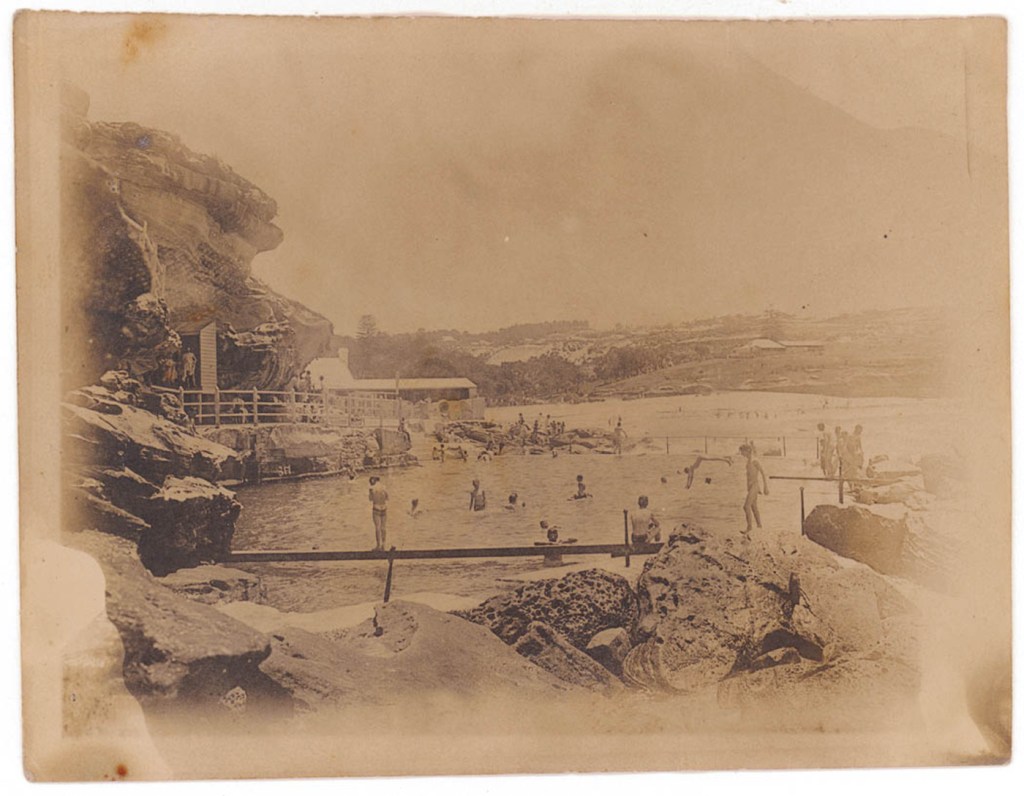

And ………. Albert William Barry (1891-1958)

From the early days of settlement, Sydney’s inhabitants bathed in the harbor and its surrounding waters, with nudity being common. As Sydney Harbour became increasingly polluted, the fresh saltwater on the coast became more appealing, leading to the popularity of ocean baths; The safest sea-bathing was initially available in the municipalities of Randwick and Waverley, in the natural and “improved” ocean pools on Coogee, Bronte, and Bondi beaches. These ocean pools, often segregated, played a crucial role in the development of swimming, surf lifesaving, and Sydney beach culture. From the 1890s, ocean pools used by men began developing into venues for recreational or competitive swimming, with amateur swimming clubs and rectangular racing courses, and spaces for spectators and officials. Men, women and children watched swimmers clad in regulation swimming costumes set world swimming records at the Bronte and Bondi baths. With the NSW government and swimming clubs sharing a belief that boys and girls should learn to swim, ocean pools became important learn-to-swim venues and school swimming venues for surfside communities. Ocean pools hosting swimming clubs and lifesaving classes also helped in developing the surf lifesaving movement. The legalization of daytime surf bathing led to a surge in beachgoers, but also resulted in numerous drownings, prompting the formation of surf lifesaving clubs; In October 1907, the Surf Bathing Association of NSW was formed, becoming the genesis of the Surf Lifesaving Movement; From the 1890s, ocean pools began developing into venues for recreational or competitive swimming, with amateur swimming clubs and rectangular racing courses; The safest sea-bathing was initially available in the municipalities of Randwick and Waverley in the natural and ‘improved’ pools on Coogee, Bronte and Bondi beaches. They date from the 1880s, predating the legalisation of daytime surf bathing. The earliest ocean pools were often segregated too – very few people actually wore bathing costumes in those “Victorian” days so protecting swimmers’ modest and respectability was a prime concern. The first surf lifesaving club was founded at Bondi in February 1907. Several others were set up soon after. On 18 October 1907 these clubs formed the Surf Bathing Association of New South Wales. Surf lifesaving clubs soon spread around the country, and the surf lifesavers became an Australian icon. Since 1907, it is estimated that lifesavers have rescued more than 700,000 people. Many of these baths were privately run, and one of the most famous of these were Wylie’s Baths that were built at the southern end of Coogee Beach in 1907. They were established by Henry Alexander Wylie, a champion long-distance and underwater swimmer.

Wylie’s Baths

During the 19th century, Sydney’s beaches had become popular seaside holiday resorts, but daylight sea bathing was considered indecent until the early 20th century. In defiance of these restrictions, in October 1902, William Gocher wearing a neck to knee costume, entered the water at Manly only to be escorted from the water by the police – but the following year, Manly Council removed restrictions on all-day bathing – provided neck to knee swimming costumes were worn. In the summer of 1915, Duke Kahanamoku of Hawaii introduced surfboard riding to Sydney’s Freshwater Beach.

Edwin Flack was the only Australian representative at the 1896 Athens Olympics and Frederick Lane was Australia’s sole swimming representative at the 1900 games, winning two individual gold medals. Women’s events were added at the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Henry Wylie’s daughter, Wilhelmina (Mina) Wylie was one of Australia’s first female Olympic swimming representatives, along with Fanny Durack.

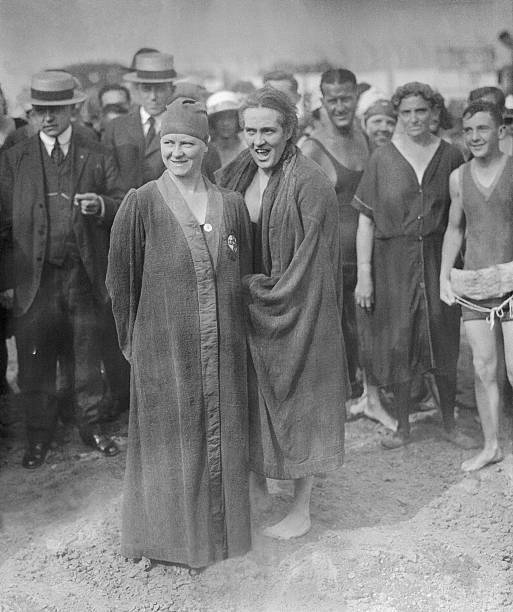

Fanny Durack and Mina Wylie won the gold and silver medals in the 100m freestyle. They were the first Australian women to become Olympic champions; and the first women in the world to win Olympic medals in swimming. It wasn’t an easy path for these two women who faced extreme sexism and public administration pettiness throughout their swimming careers.

Which brings us to Letitia and Albert’s last child: Albert William Barry.

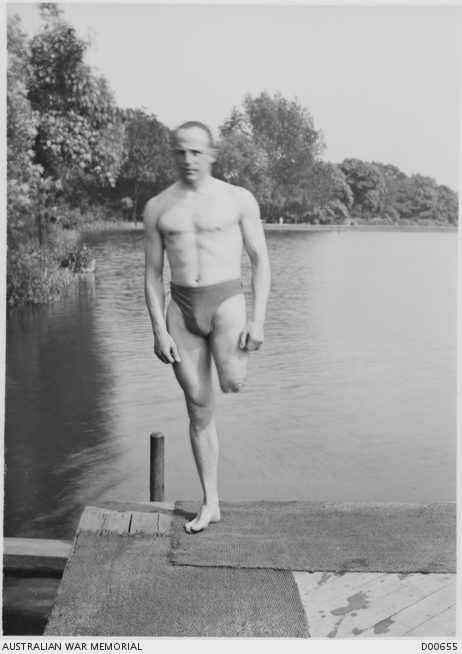

Albert William Barry had set the Australian record for the 100 yards freestyle was selected to represent Australia in swimming at the 1916 Olympics. The summer Olympics had been awarded to Berlin, Germany and were cancelled at the outbreak of WWI in 1914. Letitia and Alberts third child and only son had a fascinating and varied life complete with much personal difficulty. The East Melbourne Historical Society has written and posted a wonderful biography of Albert which I’ll copy and paste in this blog: https://emhs.org.au/biography/swan/albert_william

“SWAN, Albert William

Author: Sylvia Black

Family name: SWAN

Given names: Albert William

Alternative name: BARRY, Albert William (true)

Gender: Male

Religion: Church of England

Date of birth: 1 January 1891

Place of birth: Birth Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

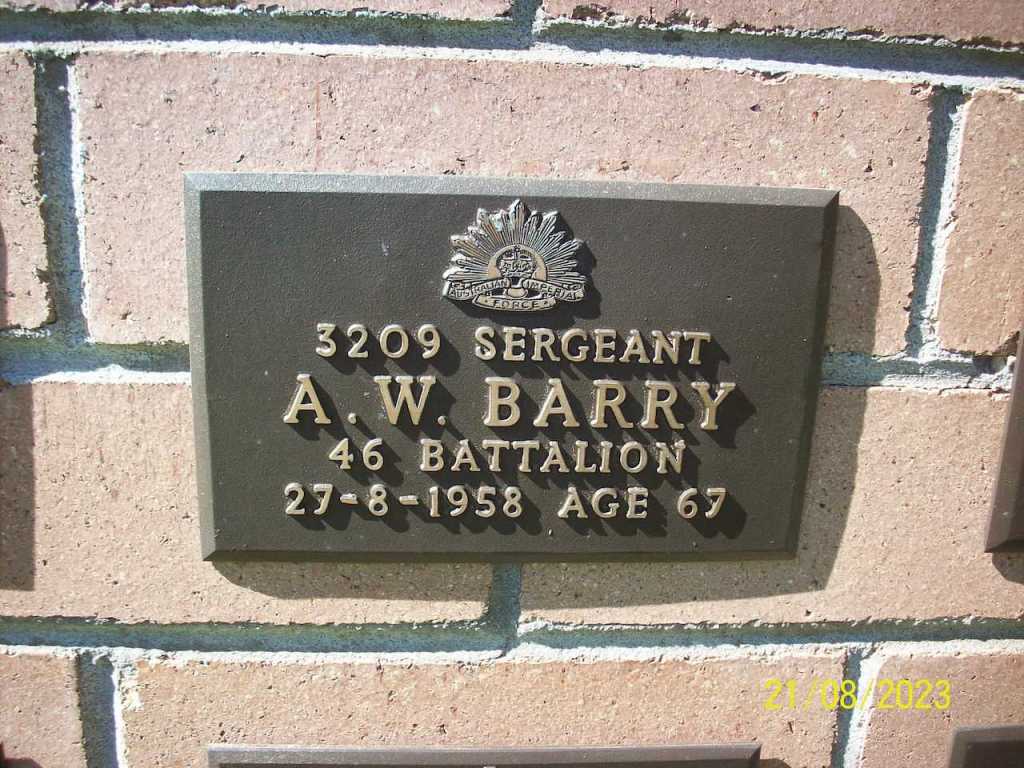

Military service: WW1 Regimental number: 3209 Rank: Pte

Military units: 46th Battalion, 8th Reinforcement

Military casualty:

Wounded

Biographical notes:

Albert William Swan was the name this soldier used when he enlisted at Perth on 24 November 1916. Over a year later, in March 1918, he made a Statutory Declaration stating that his real name was Albert William Barry. He was born in Sydney in 1891 and was the son of Albert and Letitia Barry (nee Swan). He grew up in Sydney and made a name for himself from an early age as a champion swimmer. He broke the Australian record for 100 yards in 1913, which record remained unbroken until 1927. His occupation at enlistment was agent. He gave as his next of kin his wife, Olive, address unknown. It seems his enlistment may have been a means of escape from an unhappy marriage. His own address he stated as Berry Street, East Melbourne. There is possibly another reason he enlisted under another name and in another state, his mother, Letitia, had been married previously with three sons. Her husband and her three sons had died in tragic but separate circumstances. It would be quite understandable if she did not want the risk of losing another son.

He was unusually tall, 6ft 6ins and weighed 168lbs [76kg]. He had a fresh complexion, blue eyes and brown hair. He was appointed to the 46th Battalion, 8th Reinforcements as a private and was sent to Blackboy Hill for training. He embarked from Freemantle only a month later, on 29 December, aboard HMAT Persic.

He disembarked at Devonport on 3 March 1917 and was sent to the 12th Training Battalion at Codford. He proceeded overseas on 4 June 1917 and was taken on strength of the 46th Battalion. He was appointed Lance Corporal on 2 July 1917. He was wounded in action on 17 July 1917 and was evacuated to England where he was admitted with a gunshot wound to his left leg, back and thighs. He was reported seriously ill. His leg was amputated above the knee on 2 October 1917. He was discharged for duty at Headquarters on 9 March 1918. By October 1918 he had been promoted to ER/Sergeant. He was granted leave with pay from 6 January 1919 to 6 April 1919 to attend law lectures at Middle Temple, Charing Cross. His leave was extended to allow him to attend the Council of Legal Education, 15 Old Square, Lincolns Inn. He completed his course on 31 July 1919. The Director of Education at the Department of Repatriation and Demobilization, AIF wrote, ‘Good experience gained on this course. Sergt Barry paid close attention to his work and derived considerable benefit therefrom.’ The same day he proceeded overseas to France as Officer in Charge of British Troops in Paris. He returned to Australia 28 August 1919 and was discharged 13 December 1919.

On returning home Albert qualified as a solicitor and by 1933 was Crown Prosecutor in the Crown Law Department of New South Wales. He continued to swim competitively for many years. He and Olive were divorced in 1921 and he married Estelle M Asprey in 1925. A son was born in 1926 and Estelle died a week later.”

In short, Albert William Barry (1891-1958), the son of Albert and Letitia, was a champion swimmer who lost his leg during WWI. He had three wives and three sons, rose the legal ranks to become an assistant crown solicitor and died in 1958. He was only 22 years old when his father died, the same year that he established the Australian swimming record for 100 yards. For Letitia, losing a second husband when life seemed to be going so well must have been traumatic and it is no wonder that her son would want to keep his enlistment to the army hidden from her.

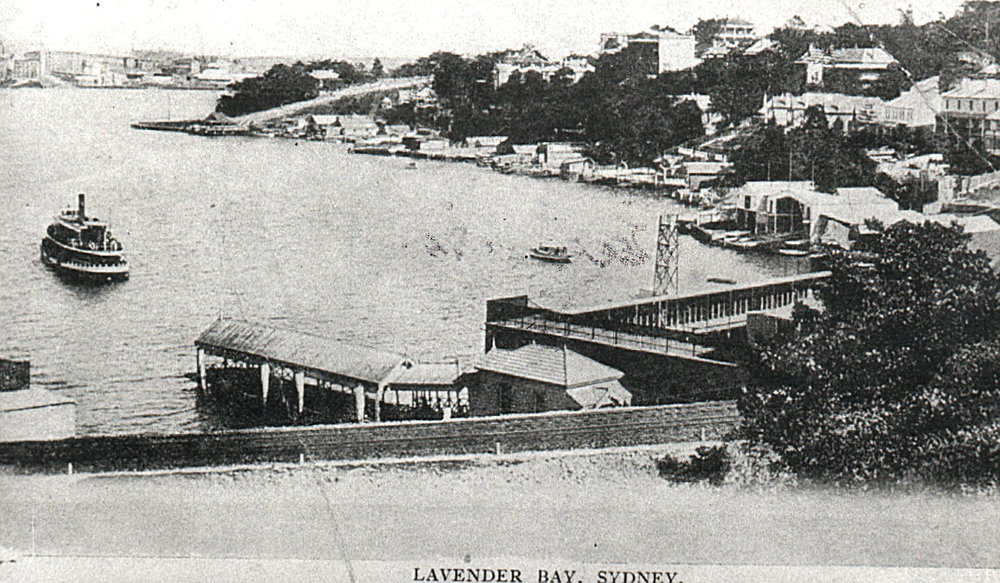

As well as swimming becoming prominent, other aquatic sports such as rowing and sailing became extremely popular. The “world’s greatest natural harbour” as Sydney harbour was so often referred to played a major part in facilitating these competitive sports. The harbour was filled with vessels: liners and cargo ships from overseas, steamers bringing and taking people and goods to and from the small ports strung along the coast. There were local schooners and skiffs and the fleet of ferries that serviced the harbour. The ferries were the means by which the northern and southern shores were connected before the Sydney Harbour Bridge. The harbour traffic was so regular and essential that, in the early 1920s, the visiting author D.H. Lawrence wrote of ‘huge restless, modern Sydney whose million inhabitants seem to slip like fishes from one side of the harbour to the other’. The Sydney writer Kenneth Slessor later described the traffic and the myriad of coves they serviced by ferries and skiffs as giving rise to ‘a dispersed and vaguer kind of Venice’.

A major European war loomed, then in 1914 was declared, ironically because three descendants of Queen Victoria had huge egos, limited foresight and were advised by an increasingly influential and self-serving political class. What was Australia and in particular, Sydney, like in 1913, the year that Albert Barry died and his son Albert William Barry established the 100-yard swimming record which was unbroken for the next 14 years?

In no particular hierarchy of importance these items give us a clear snapshot of Australia at the outbreak of “The Great War”:

Australia’s 1911 Census recorded the population as 4,455,005 with the median age of 24 years old. Just over 4 per cent of the population was aged over 65, in a category named “old age”, and men between 15 and 64 made up almost two-thirds of the population.

Sydney was the biggest city, Hobart the smallest.

The Immigration Act of 1901 restricted migration to people primarily from Europe, meaning the country was largely Caucasian and in 1914 there were no accurate figures about the size of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community. Indigenous Australians were excluded from the Census, denied civil rights under the Constitution, and disenfranchised from voting.

The Defence Act also prohibited Aboriginal people from serving in the military, but despite that, more than 400 Indigenous men went to war. They were given equal pay during the course of the conflict.

Australia enjoyed a high level of literacy, with 96 per cent of the recorded population older than five able to read. However, many children from working class families had to leave school before the age of 12 to do a trade.

Agriculture and manufacturing were driving a prosperous Australian economy in 1914. The pastoral industry was at the centre of economic activity and exports were increasing as slower sailing ships were replaced by coal-burning steam ships.

The basic wage for Australians was 8 shillings a day That’s about $43 in today’s money.

In some cities, the rent for a three-bedroom house with a kitchen was 12 shillings ($65) a week, and general expenses (not including food and rent) were about 14 shillings ($75) per week. According to the New South Wales Industrial Court, the “living wage” for a family of four was 48 shillings ($232) a week.

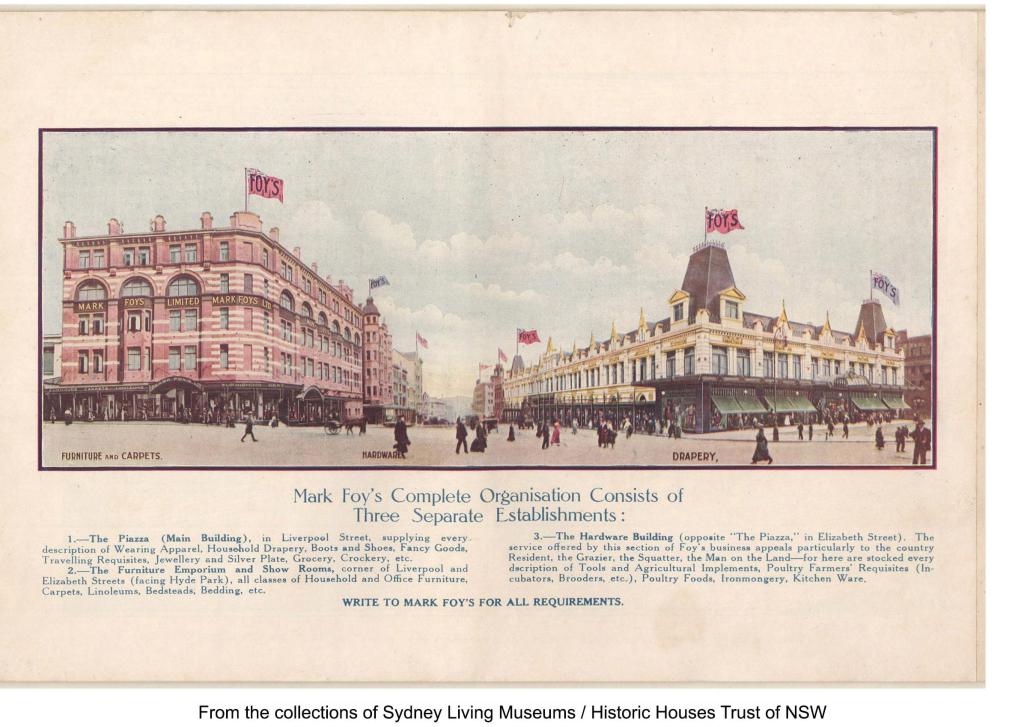

In 1914, Melbourne was the seat of the federal government and also the nation’s de facto shopping capital. “Melbourne was a rich and sumptuous city, not that distant from Paris or London in its facilities and demeanour,” historian Michael McKernan said. The first Coles variety store opened in 1914, selling hardware, haberdashery, stationery and kitchenware, with nothing costing more than one shilling. Mark Foy’s was a popular Sydney-based department store. Its 1914 winter catalogue showcased 108 pages of fashion, including corsets and hats.

Australia’s passion for sport was already entrenched. Athletes such as Snowy Baker, Annette Kellerman, Victor Trumper and Dally Messenger represented the country in swimming, boxing, cricket and football. Neck-to-knee bathing suits, full-length tennis skirts and wool breeches were worn by sporting stars. Swimmers Fanny Durack and Mina Wylie won gold and silver medals at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics.

The tango came to Australia from the salons of Paris, sparking a “tangomania” craze, but not everyone approved. The Palais de Danse in Melbourne was the scene of protests against the “immoral” dance.

Australia had a thriving film industry and even developed a genre of bushranger films, a nod to Robin Hood and his Merry Men perhaps?

The quality of recorded music was improving and many families had gramophones, enabling them to listen to concerts and opera. With amateur photography on the rise, more Australians were buying their own cameras.

A wireless telegraph station was installed in 1912, enabling Sydney and Melbourne to be connected by telephone. There were soon 2,530 private lines in the country, but the telephone was primarily for business and the printed word was how Australians kept in touch and up with the news. “Newspapers were really, really extensive and substantial and news was spread by the paper boy yelling out headlines on the street,” historian Michael McKernan said.

The first Commonwealth postage stamp was issued in 1913. It featured a kangaroo on a map of Australia and sold for one penny. The first airmail delivery took place in July 1914, when Frenchman Maurice Guillaux flew the nine hours from Melbourne to Sydney in a wood and fabric Bleriot monoplane. On board were 1,785 postcards.

Cars were making their mark on Australian roads by the time war broke out. Melbourne had new electric trams but horse and cart, bullock trains and bicycles were still the main forms of transport. The construction of the last leg of the transcontinental train line began in August 1914 with the goal of finally linking every state, including Western Australia, by rail.

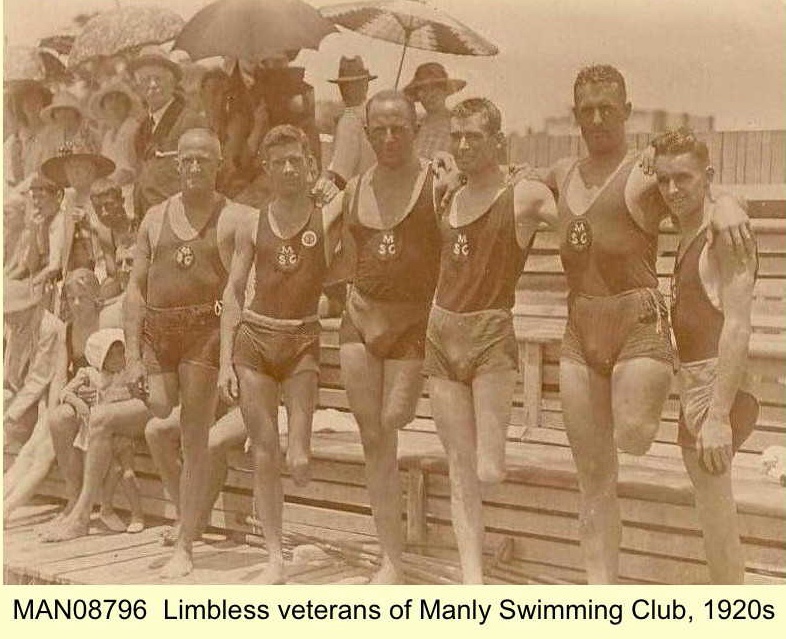

War years are never good years. Letitia’s great nephew, Caleb Hutton Vacchini joined up at only 16 and spent his “Great War” in Flanders and France. Caleb and Albert William Barry were 1st cousins, 1 X removed. Albert William Barry was able to study and qualify as a solicitor in 1919 when he returned to Australia. As testament to his resilience, he continued to swim competitively and was instrumental in the creation of limbless swimming competitions for veterans. By 1933 he was a Crown Prosecutor in New South Wales.

The middle Barry child, a daughter who shared her mother’s name, Letitia, married a George Harold Sears (1890-1951) in Sydney on the 24th March 1914. They had three children, two sons, George (1917-) and Robert (1920-), and a daughter Margaret (1914-). Letitia (Barry) Sears lived into her 70’s, and died two years after her brother, Albert William Barry (1891-1958) in 1960.

Three years after the end of World War I, the renowned historian Charles Bean described the Australian national character as having “Qualities of independence, originality, the faculty of rising to an occasion and loyalty to a ‘mate’”. For Bean, the idolised spirit of the Anzacs born at Gallipoli and on the Western Front had become ingrained in the character of the whole nation. More than 60,000 Australians were killed during the four-year conflict; the number of injured, imprisoned or missing was more than 150,000. Those returning from the war in 1918 were promised “homes fit for heroes” in new suburbs such as Daceyville and Matraville. “Garden suburbs” and mixed industrial and residential developments also grew along the rail and tram corridors.

At the end of the First World War, in 1918 and 1919, an influenza pandemic killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide. The disease spread quickly in Europe because of the war. Soldiers were crowded and lived in poor conditions. Military hospitals became virus hotspots. Widespread international travel by sea helped spread the flu to every continent, especially as soldiers returned from the war. As an island, Australia was able to quarantine people when they arrived by sea. All the same, up to 15,000 Australians died of the flu in 1919, and in Sydney alone 3,500 died. Probably between a quarter and a third of Australians caught the flu. First Nations communities were badly affected by flu and made up nearly a third of those who died from flu in Queensland in 1919.

Post war, in the first few years of the 1920’s, Qantas Airlines was founded; Edith Cowan was the first woman elected to an Australian Parliament; the British Empire Settlement Act passed by Commonwealth Government to encourage British immigrants; and compulsory voting in Federal elections was introduced. The government created jobs with massive public projects such as the electrification of the Sydney rail network and the Sydney Harbour Bridge, which linked road and rail traffic between Sydney’s northern and southern shores. Construction began in 1924 and took 1,400 men eight years to build at a cost of £4.2 million. On the 9th of May 1927, the Duke of York, later to become King George V, opened Parliament in Canberra. The population of Sydney reached one million in 1926, and it regained its position as the most populous city in Australia.

Overall, the 1920s heralded the brave new world that emerged from the devastation of World War I. Australia’s allegiance to the British Empire’s war effort had come at a high price: thousands of young men had been slaughtered, families had been dislocated, and returned soldiers often struggled to fit back into the rhythms of society. Similar stories played out in other countries around the globe. Eager to put the horror and drudgery of war behind them, people began rebuilding their lives.

The Roaring Twenties saw dramatic changes in technology, entertainment, architecture and society. Young women sought new freedoms, movies began influencing the way people lived, and technological developments such as faster, more reliable motor cars improved the lives of millions. Police forces, their numbers reduced by war, were caught on the back foot as organised crime sought to take advantage of these changes and freedoms. The policing work was made harder by the fact that laws did not always keep up with the pace of criminal evolution.

The upsurge in organised crime began after the prohibition of sale of cocaine by chemists, the prohibition of street prostitution, the criminalisation of off course race track betting and the introduction of 6:00pm closing for public bars. Illegal drug distribution became a serious social problem due to the concentration of addicts in Kings Cross, Darlinghurst and Woolloomooloo estimated at five thousand.

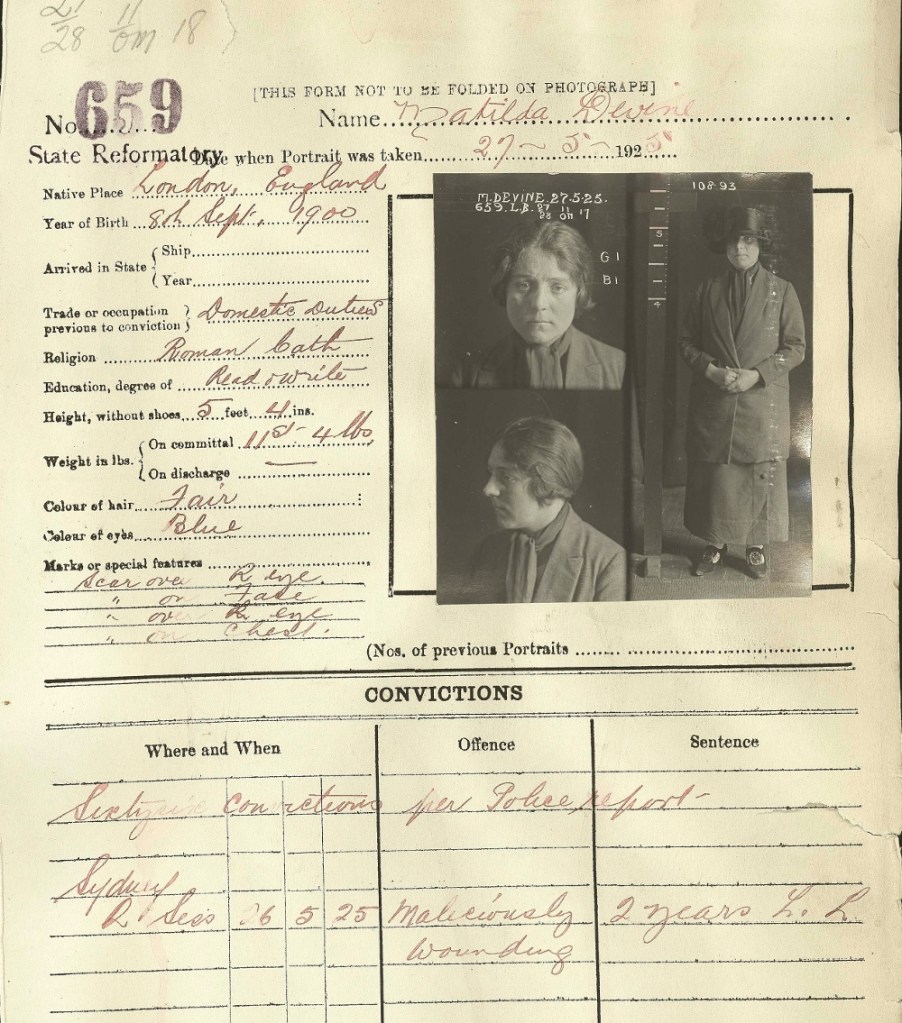

After handguns were criminalised in New South Wales in the late 1920’s, razors became the weapon of choice amongst Sydney gangsters. Razors became a default weapon due to the ease of purchase from barbers’ shops for a few pence, the ease of concealment and its use as an instrument of intimidation and mutilation. It has been estimated that there were over five hundred slashings within Sydney during the heyday of intensive razor gang criminal activity, which was overseen by two women. Tilly Devine, known as the ‘Queen of Woolloomooloo’ ran a string of brothels centred around Darlinghurst and the Cross, and in particular, Palmer Street. Kate Leigh, known as the ‘Queen of Surry Hills’, was a sly grogger and fence for stolen property. Devine and Leigh’s battle for supremacy led to a running battle in the streets of Sydney that left many people dead, disfigured or doing gaol time.

The suburbs that this underground war was carried out in were the same suburbs that Albert and Letitia has established their Butcher Shops in the early 1900’s. The nature of all cities is continual adaptation to “changes in technology, entertainment, architecture and society.” We have noted that almost one hundred years earlier, “tightly packed terrace houses were built. These houses, with their balconies and decorative cast-iron railings, are now Sydney’s most attractive heritage from the past.”

During the post-war period, people moved away from the inner suburbs of Sydney to modern housing made more accessible by motor cars and public transport. “Our” Letitia (Swan) Hyland/Barry was 62 at the end of the war and records show that in the 1920’s she was living at 5 Piper Street Annandale, next door to her daughter Elizabeth and son-in-law Percy Sinclair Tooker who were in number 7 Piper Street with their family. About two blocks away the younger daughter, Letitia and her husband George Harold Sears (1890-1951) were living at 216 Annandale Street in the same suburb. Annandale is about ten miles from the heart of Sydney and was considered to be far from the centre. But population growth, transportation and opportunity ensures that cities continue to spread further out from their original centres. And Sydney had a lot of space to spread. By the end of the 1940’s much of Sydney’s population lived about 25 miles from the city centre. Business opportunities were always present as the technical innovations converged with the publics demands. From the Family Notes:

George Sears was a “hot water and ventilation engineer”. He had his own company, and with the technical and social developments that were taking place at the time, I think he was in the right place at the right time, there being I think many opportunities for his business, including contracts to install air conditioning in cinemas in Sydney. As a result his business did very well and he was able to pass this successful business on to his sons.

The 1930’s saw Letitia and George Sears move to the eastern coastal suburbs of Sydney – Coogee and Maroubra. Her mother, Letitia, now well into her 70’s also moved out in that direction, living on Rainbow Street which straddled both Coogee and Randwick. Elizabeth (Barry) Tooker and her husband Percy had taken advantage of the Sydney Harbour Bridge and moved north, past Chatswood to the suburb of Roseville in the mid 1930’s.

Sport was still a very strong focal part of Australian life.

In January 1924, ten thousand people crowded in to the Domain Baths, Woolloomooloo Bay to watch the 440 yard (400m) race between Sydney legend Andrew Boy Charlton and European champion, the Swede Arne Borg. Boy beat Borg equalling the world record time of 5 min 11.8 sec. A dinghy was dropped into the pool by spectators which Borg then rowed Charlton around the pool in on a victory lap shouting “Charlton is champion! Charlton is champion!” They raced again over 880 yards this time Charlton beating Borg and setting a new record of 10 min 51.8 sec.

And in a Sheffield Shield cricket match at the Sydney Cricket Ground in 1930, Don Bradman, a young New South Welshman of just 21 years of age, achieved the highest batting score in first-class cricket with 452 runs not out in just 415 minutes.

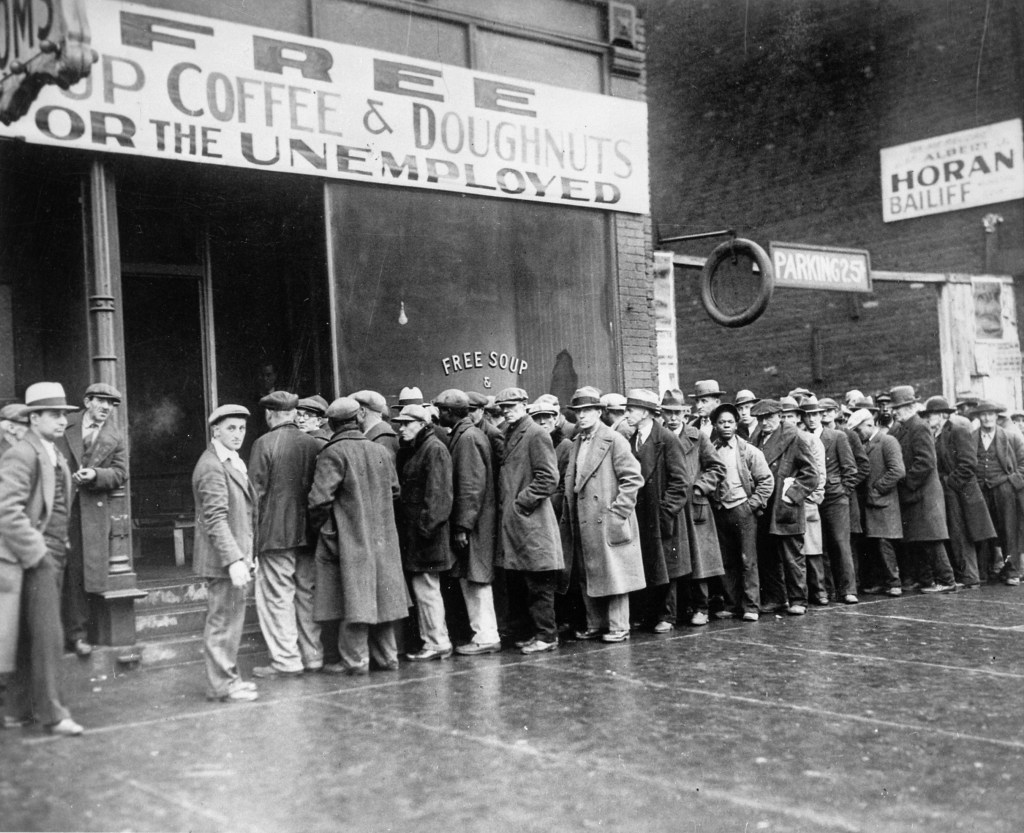

Then, possibly as now, greed and arrogance in the United States of America led to a stock market collapse and world-wide depression.

Sydney was more severely affected by the Great Depression of the 1930s than regional NSW or Melbourne. New building almost came to a standstill, and by 1933 the unemployment rate for male workers was 28 per cent, but over 40 per cent in working class areas such as Alexandria and Redfern. Many families were evicted from their homes and shanty towns grew along coastal Sydney and Botany Bay, the largest being “Happy Valley” at La Perouse. The Great Depression peaked in 1932 and lasted for almost ten years and greatly affected all levels of life in Sydney. It forced the change in Australia’s economy from an agrarian base to manufacturing and ironically WWII was a factor in bringing it to an end.

Letitia, her children and grandchildren appeared to have survived, as many people did.

Letitia Swan/Hyland/Barry has a recorded death date of 18th February 1943 in Randwick at a Convalescent Home at 85 Perouse Road. Her death was classified as arteriosclerosis, a likely term for old age. Letitia was cremated which was not the “norm” at that time. She lived to 86 and during those nine decades she had seen the rise and fall of many fortunes; the relentless expansion of the city she was so fond of; global wars; two husbands and nine children; tragedy, comedy & joy.

I do hope that she was able to maintain a strong contact and connection with her family as they weathered the tough times brought about by the Great Depression. We have seen how close-knit the Swan and Cain children were back in the second half of the 19th century and how they embraced the expanding and extended family. Letitia’s early life was not easy and she had to negotiate many dark times. I like to think that despite any setbacks she encountered, she did live a life that resonated with her names meaning: celebration, mirth, cheerful and lively. It was most gratifying as this little story neared completion that I was able to contact Margaret Davies-Slate, one of Letitia’s great granddaughters. Margaret very kindly gave me family notes and memories of Letitia and her extended family. The stories show Letitia as a very happy, involved and supportive daughter, sister, mother, grandmother and great grandmother who had a great zest for life and a resilience that exemplified her courage in navigating a very difficult path.

~~~~~~~~

WHO IS WHO?

Letitia (Swan) Hyland Barry is a granddaughter of Sarah (Murray) Cassidy

Roger Irving is a 2nd great grand nephew of Letitia (Swan) Hyland Barry

Margaret Letitia Davies-Slate is a great granddaughter of Letitia (Swan) Hyland Barry

Cathy (Parry) Shaskof is a 1st cousin 3x removed of Letitia (Swan) Hyland Barry

Selma Janet McGoram is a half 2nd great grand niece of Letitia (Swan) Hyland Barry

Pat (Rule) Crook is also a half 2nd great grand niece of Letitia (Swan) Hyland Barry

Roger & Margaret are 3rd cousins 1x removed

Cathy & Margaret are 4th cousins

Selma & Margaret are half 3rd cousins 1x removed

Pat & Margaret are half 3rd cousins 1x removed

And we are all Cassidy Cousins, descendants of Sarah (Murray) Cassidy (1797-1873) whose story can be found on this blog.

Resources and Acknowledgment

None of this work is mine; I have simply read, absorbed and regurgitated in a rather haphazard manner. However I must thanks the Cassidy Cousins for their continual support, encouragement and accuracy checking – Selma, Pat and Cathy, you are wonderful.

Special thanks to our especially qualified accuracy checker – that would be you Cathy! Our own font of knowledge.

And so many thanks to a newly discovered cousin, Margaret Davies-Slate who provided some gorgeous human colour to this story; hopefully we’ll get her to wander over to this side of Australia for a lunch sometime.

And yes, all the great stuff to be found in books and on-line. I promise I’ll do most of that next week, I do have a lot of it already collated.

Parliament.nsw.gov.au

Wikipedia: History of Sydney

Museums of History NSW http://www.mhnsw.au

Sydney Harbour Trust. http://www.harbourtrust.gov.au

The Dictionary of Sydney.org

Abc.net.au

Leave a comment