One of the most interesting branches on the Family History tree is the descendant line of Sarah Murray and Cormick Cassidy who were from the Irish border town of Monaghan. They were my 4th great grandparents and Sarah Murray’s story can be found in another entry in this history blog simply titled “Sarah (Murray) Cassidy.”

Sarah and Cormick had a son, and three, probably four daughters according to her convict records. Four of her children arrived and remained for the rest of their lives in the “terra Australis” colonies. There is still some uncertainty about the fourth daughter.

Sarah arrived in Sydney on the 30th of May 1837 aboard the convict ship “Margaret” with her two daughters, Mary Anne (1826-1914) and Elizabeth (1829-1869) who were ten and eight years old respectively.

Catherine “Kitty” Cassidy (1818-1850) arrived in Sydney on the 25th of December 1837 aboard the convict ship “Sir Charles Forbes” as a single 19-year-old who had been sentenced to transportation for robbing Thomas Campbell of £2.10s. in banknotes in Monaghan on 25th December 1836.

John Cassidy (1814-1879) arrived in Hobart Town, Van Dieman’s Land on the 9th of March 1842 as a soldier with the 99th Foot Regiment on board the “Richard Webb”.

Margaret Cassidy (1815-1854) whose lineage is yet to be verified, arrived in Hobart Town, Van Dieman’s Land on the 19th of March 1849 on board the “Mary Ann”.

This essay will give some background to the family of Cormick and Sarah, primarily focussing on the eight children of Elizabeth Cassidy (1829-1869) and her second husband, William Swan (1820-1895). It will also include information on the four children of Elizabeth Cassidy (1829-1869) and her first husband, Thomas Cain (1815-1853).

Elizabeth Cassidy and William Swan were my 3rd great grandparents.

Elizabeth is variously known as Lizzie, Bessie or Betsy in the many family trees, however for this story I will refer to her as Bessie Cassidy. I’ll differentiate the William Swans with senior (Snr.) and junior (Jnr.)

On arrival in the Colony, Sarah and her daughters were either kept on board the “Margaret” for processing, or rowed up the river to the Female Factory at Parramatta. The two young girls, Mary Anne and Bessie, were transferred to the Female Orphan School in Parramatta on the 14th of July 1837. It was typical for children over the age of four to be separated from their mother and placed in the Orphan School.

In September 1837 Sarah had her workplace assigned, to a Richard Linley. He very kindly gave his “permission” for Sarah to marry when she applied to the Governor. Banns were published and Sarah married a free settler, William Marsh at St. Phillips Church in Sydney on the 26th of December 1837.

The British system of crime and punishment involved recording all aspects of processing individuals from arrest, trial, sentencing, transportation and prison. At every part of this process all details were documented and musters recorded. There could be more than a dozen points of contact that an individual’s details would be entered into the legal paperwork. The convicts were an asset that needed to have their history properly processed. This processing did not guarantee fair and humane treatment. As a substitute for indentured labour, the convicts were an essential and very cheap cog in the workings of the colonial sausage machine.

Consequently, there is very often more information available about convicts than free settlers. Convicts were also considered valuable property because it was very apparent in the first few decades that the survival of the Colony would require the commitment and involvement of a large number of them. It became policy to issue tickets of leave and freedom certificates earlier than originally planned to convicts who were known to be both industrious and possessing skills such as building, farming and animal husbandry. Another incentive that was applied very early in the establishment of the Colony was the granting of land to convicts who had been given these freedoms.

It is widely accepted that despite the greater majority of convicts being unable to read and write, they were well aware that being transported could result in being granted land – something that would never happen in England, Scotland, Wales or Ireland. A “bush telegraph” existed between convicts, freed convicts and settlers in the Colonies and their families and associates back in the northern hemisphere, which served to exchange all sorts of family news and valuable information. Certain crimes would result in transportation for seven or ten years which was a desired outcome. Other crimes may have resulted in a death sentence or imprisonment for “the term of their natural lives”.

Bessie Cassidy, who arrived in Sydney as an eight year old was married twice in her life. She was first married to a Thomas Cain (1815-1853), an English soldier from the Isle of Man who was a member of the 99th Foot Regiment. By 1855 John Cassidy, the older brother of Bessie, had been promoted, first to corporal and then to Sergeant. After their arrival in Hobart, the 99th had been sent to New Zealand, to Sydney and to Port Macquarie. There would be no doubt that families would meet up with and get together whenever possible, so Bessie would have had ample opportunities to socialise with Thomas Cain.

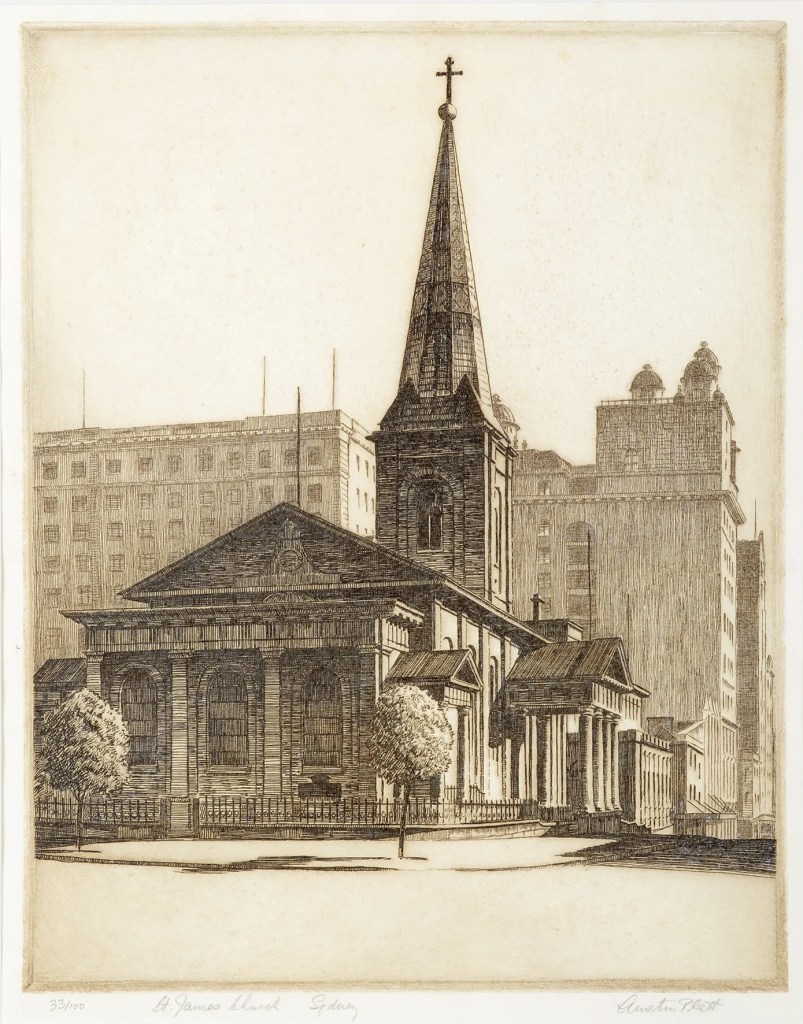

They married at St James Church Sydney on the 24th of December 1844, just six weeks after Bessie’s 15th birthday. Her brother John may not have been present, but her stepfather, William Marsh was present and is noted as a witness on the marriage certificate.

Bessie and Thomas Cain had four children –

Mary Ann Cain (1845-1886), born in Sydney;

James Hunter Cain (1847-1902), born in Hunter River;

Sarah Eliza Cain (1849-1916) born in Kingston, Norfolk Island;

and John Cain (1852-1886) born in Sydney

Thomas Cain, as a soldier with the 99th Foot Regiment, was at the beck and call of the Governor and did not have a permanent abode. As the Cassidy families grew, living with or near family was high on the wish list.

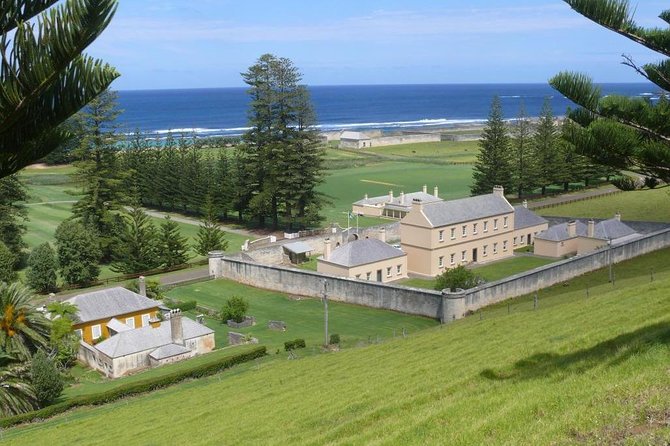

In 1848, Sergeant John Cassidy and Thomas Cain, with their wives and children, were posted to Norfolk Island with the 99th Regiment.

Tragedy struck the family soon after arriving.

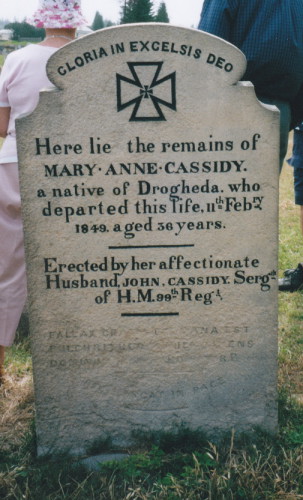

John’s wife, Mary Ann Cundy (1813-1849) died from complications during the birth of their sixth child, a daughter Mary Anne on the 11th of February 1849. Death via childbirth was a much too common fate for women during Australia’s early history.

Bessie was also pregnant and gave birth to her second daughter, Sarah Eliza Cain on the 7th of September 1849 at the small settlement of Kingston on Norfolk Island.

During the 1840’s Bessie’s sisters were living in the Hunter River region to the northwest of Sydney.

Bessie’s eldest sister, Catherine, (1818-1850), had married a fellow convict, Robert Vincin, in Maitland in 1839, had two children and was living in this area until her death in 1850.

The middle sister, Mary Anne Cassidy (1826-1914) had also settled in the Hunter region and started a family. She married an ex-convict, John Locke in 1845, only two weeks after Bessie had married Thomas Cain in Sydney. Mary Anne and John were married at Phoenix Park, just north of Morpeth. The Locks had 14 children and John worked as a leasehold farmer throughout the region, never owning farmland. The family moved to Sydney in 1851 after the death of their daughter Catherine. When they moved back to Hinton in 1853 John became a storekeeper and bought and sold six different town blocks until he declared bankruptcy in 1862. He continued to work as a labourer and leasehold farmer until 1873 when he moved north to Nemingha, a few miles from Tamworth where his son had settled.

On the 27th of June 1853 in Sydney, Thomas Cain, the man from the Isle of Man died at the age of 37.

Shortly after, Bessie married William Swan in Sydney on the 28th of July 1853.

The William Swan who married Bessie (Cassidy) Cain was born about 1819/1820, possibly in Quebec, Canada. Like many individuals who were not convicts in the colonies of New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania in the first half of the 19th century, there is very little information that exists about William Swan prior to his marriage in July 1853. We can’t verify his birth, his family, nor his arrival into New South Wales. Convicts, however, were much more likely to have their life recorded at every juncture. The marriage certificate of 28th July 1853 between William Swan and Elizabeth Cain simply states that he is a bachelor from Chippendale, Sydney and that she is a widow from Redfern. The Presbyterian Minister was James Fullerton, L.L.D. Minister of the Scots Church, Pitt Street.

Here are the seven Sydney Swans born to Bessie and William Swan Snr.:

William Swan (Jnr.) (1854-1887)

Letitia Swan (1856-1943)

Thomas Cormick Swan (1858-1943)

Louisa Alice Swan (1860-1941)

Aden/Haydon Swan (1863-1933)

George Swan (1865-1867)

Elizabeth Swan (1867-1889)

Their first child, a son, William Swan Jnr., was born in Newtown on the 28th of January 1854. Basic math indicates that either of Bessie’s husbands could have been William’s father.

The next three children were born at West Maitland, an important trade centre and farming hub in the Hunter Valley, more than 170kms from Sydney and 25kms west of Newcastle. Bessie’s sisters, Catherine, (1818-1850), and Mary Anne (1826-1914) had both married and were living in the farming region around West Maitland and the Hunter valley from the late 1830’s. It seems highly likely that Bessie would have lived in or around West Maitland to be close to her family even though Catherine died in 1850.

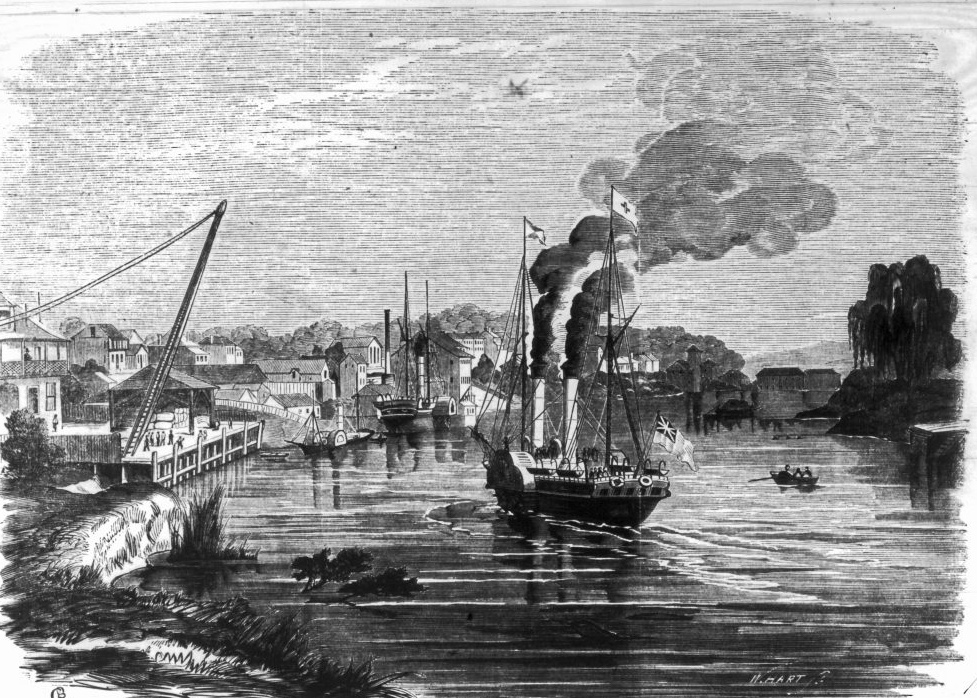

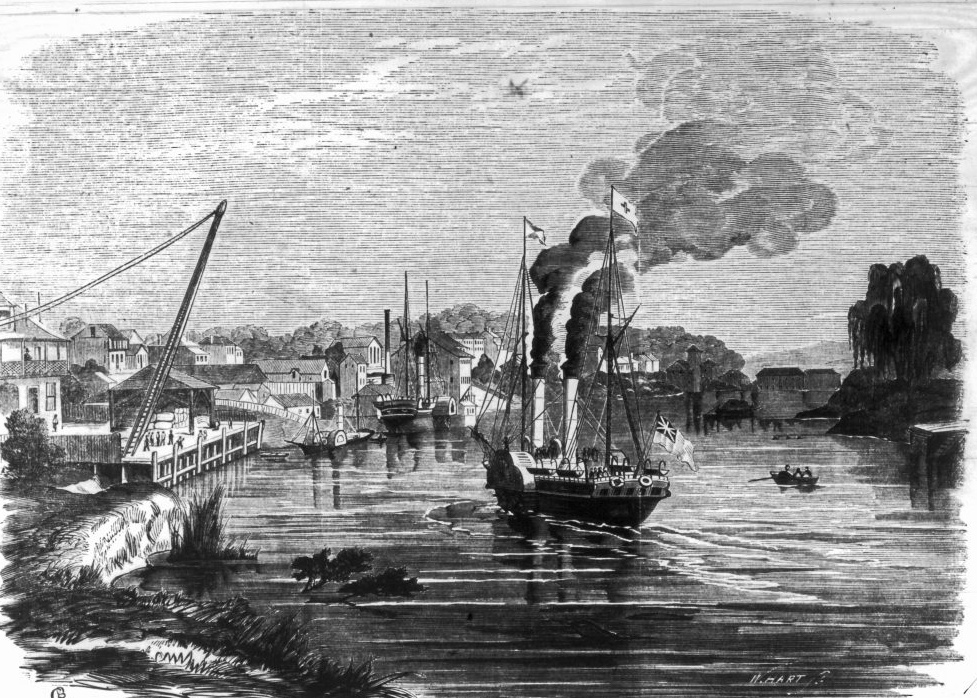

Transport to and from Norfolk Island was of course by ship, which was also the most efficient way of getting between West Maitland and Sydney. West Mailand’s neighbouring river lands, the Wallis Plains, had been utilised for timber felling and farming from as early as 1816 when a penal settlement was built near what is now Newcastle. As noted earlier, many convicts were granted land when they received either a ticket-of-leave or Certificate of freedom. The Hunter River enabled shipping as far inland as Morpeth and goods were transferred by smaller boats to Maitland.

Louisa Alice Swan, the fourth child, born in July 1860, was baptised in West Maitland on the 2nd of December 1860. The Swan family were living in West Maitland at that time and the 16-year-old Mary Anne Cain (Bessie’s first child to Thomas Cain) married William Hurwood (1838-1916) on the 26th of December 1860. It appears that the Hurwood branch of the family moved back to Sydney soon after, most likely by the end of 1861.

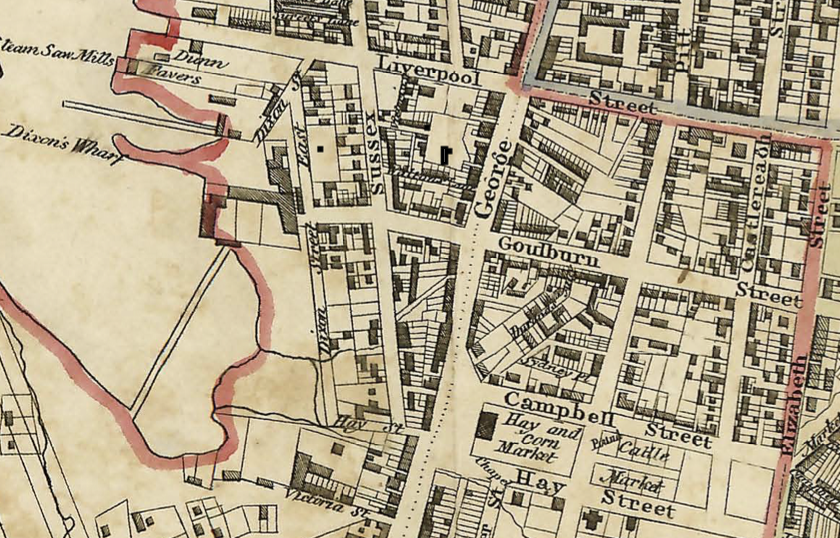

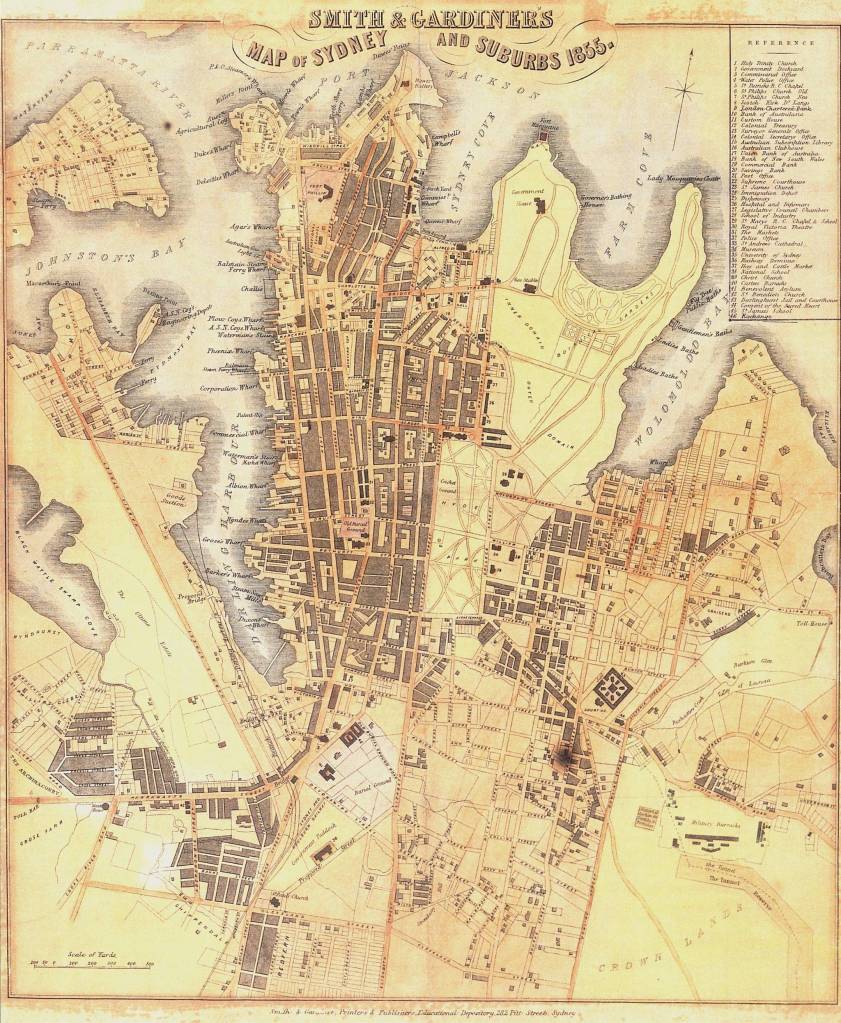

William Swan Snr., a tinsmith, probably felt that there were greater opportunities for his business in Sydney. Perhaps the rural life didn’t suit him; perhaps it was a family consensus to move to Sydney where they could live in closer proximity to each other. In any case we know that he, Bessie and the family were living in Sydney in 1862 or 1863. He appears in Sands Commercial Directory of Sydney as a tinsmith at 9 Sussex Court, just around the corner from 48 Dixon Street, where William and Mary Anne Hurwood were living. Bessie and William’s fifth child, Aden Haydon Henry Swan was born in Sydney in April 1863.

Another son, George was born in Sydney in 1865 but tragically passed away in infancy in 1867.

And lastly, Bessie’s namesake, Elizabeth, is born in Sydney on the 24th of September 1867.

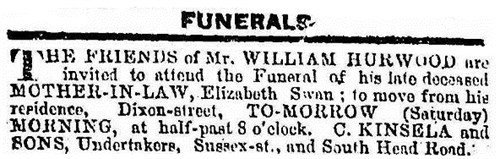

Bessie had given birth to eleven children in twenty-two years. She died in Sydney on the 30th of December 1869, not long after her 40th birthday. She was at 48 Dixon Street, Sydney when she died, the home of her daughter and first child, Mary Ann (Cain) Hurwood. Her son-in-law, William Hurwood arranged the funeral and placed notices in newspapers.

William Swan Jnr. 1854-1887 was the eldest of the eight children and at the time of his death was a tin miner: possibly influenced by his father’s profession and the lure of “striking it rich”.

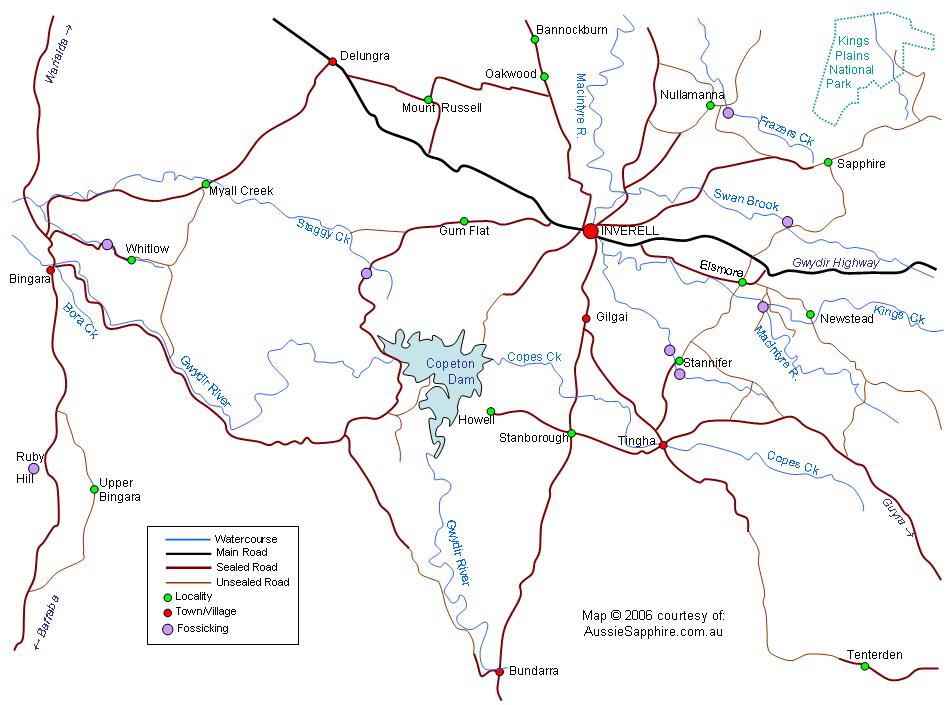

There are a number of documents, records and entries that may be of our William Swan, but nothing that can be verified until we find the birth record of his first child, a daughter, Elizabeth who was born on the 11th of June 1883 in Inverell, New South Wales. A second child, also a daughter, Louisa May (my great-grandmother!), was born on the 9th of May 1884 in Bundarra which is in the New England region of northern New South Wales, about 50kms south of Inverell. William Swan and the mother of these two daughters, Jane Emily Hill (1867-1921) were married a year later on the 11th of July 1885 at Gilgai, another small town in the same New England region.

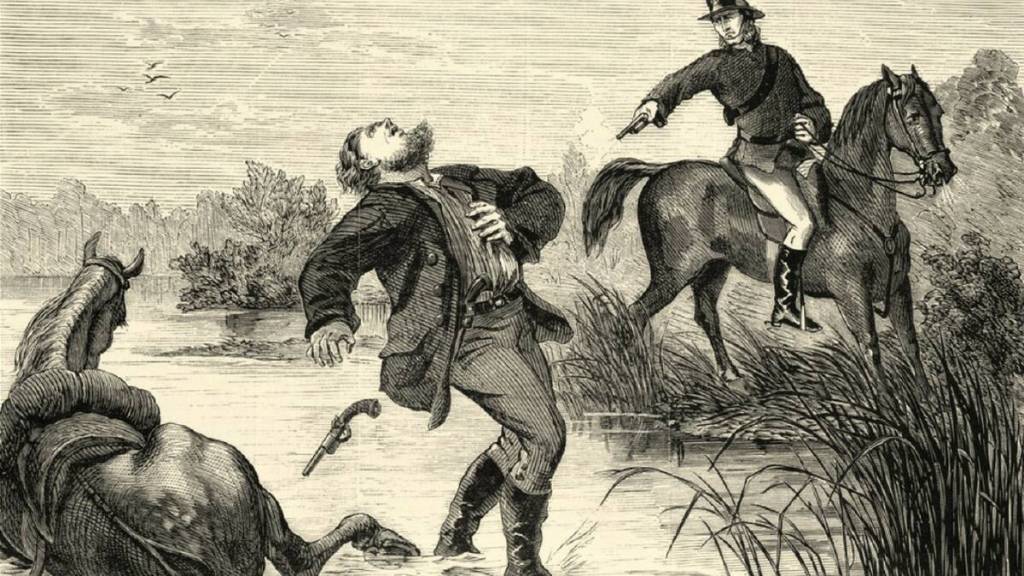

William Swan Jnr. was 29 years old when his first daughter, Elizabeth was born. He may have been attracted to this part of New South Wales by some small finds of gold and gemstones that had been reported as early as the 1850’s. Tin ore was also found but deemed too poor to be of great value. Large sheep and cattle runs were the predominant agricultural industry in this area. However, there seems to be enough wealth generated to attract bushrangers. The 1860’s saw a famous Australian bushranger, Frederick “Fred” Ward, better known as Captain Thunderbolt, rule the highways and byways of the New England High Country. Thunderbolt, an excellent horseman carved out a career robbing mailmen, travellers, inns, stores and stations. He was something of a folk hero having escaped from Cockatoo Island in 1863 and developing a reputation for avoiding violence and behaving in a gentlemanly manner towards his victims. Thunderbolt was shot dead by a constable in May 1870 which was around the same time that the discovery of tin in the area saw an influx of mining operations.

I am unsure of exactly when William Swan Jnr. made his way north from Sydney and began the arduous task of extracting ore from the ground. We do know that his half-brother, John Cain (1852-1886) had also moved north to the New England region where at Inverell in 1874 he married Mary Erwin, the daughter of Irish parents who was born in Murrurundi, a small town about halfway between West Maitland and Inverell. They were living in the area, mainly at nearby Warialda and had six children before John died in 1886. His cousins, Joseph Lock (1846-1889) and John Lock (1847-1938), the eldest sons of John Lock and Mary Anne Cassidy also moved to Inverell about 1874. They were both involved with tin mining at Tingha.

Mining became a staple of the area from the 1870s with tin, sapphires, zircons and diamonds all being commercially exploited. This part of the New England is still well known as a fossickers playground and the Inverell area has long been a source of much of the world’s sapphire supply.

The first whites in the district were probably convicts who escaped from chain gangs in the Hunter Valley as early as the 1820’s. When white settlers arrived the convicts sometimes received pardons in return for acting as guides and interpreters. The early explorer, Alan Cunningham became the first European to pass through the district on his ground-breaking trip to the Darling Downs in 1827.

Other pioneers in the region were Peter McIntyre, a scotsman with a very good reputation for farming and one of his overseers, Alexander Campbell. Campbell had his passage to the colonies paid by T.P. Macqueen, a British MP who had invested large sums of money into New South Wales and received grants of 20,000 acres. Macqueen had appointed McIntyre to select his 20,000 acres and to manage his venture. McIntyre led an entourage of 27 who arrived in Sydney in 1825. Initially favouring and selecting land near Aberdeen in the Hunter River Valley, McIntyre and Campbell travelled north to the New England region in the 1830’s as the Hunter Valley venture was facing bankruptcy.

If the name Peter McIntyre rings a bell it is because his property, Keera, was where the survivors of the Myall Creek Massacre tried to find refuge in June 1838. However, the settlers followed them and killed ten more.

I am relaying this background because there is a family connection. One of the other overseers working with McIntyre and Campbell was a Richard Alexander Wiseman, a son of the quite famous convict Solomon Wiseman who established the Wiseman’s Ferry on the Hawkesbury River. Richard was supposedly the man who marked the route north which was later built by convicts and became known as the Old Great North Road.

The Old Great North Road was built to link Sydney, New South Wales with the Hunter Valley and Newcastle. Constructed from 1826 to 1836 by convict labour and stretching for 240 kilometres, the road commenced at the Great North Road, Five Dock, passed through Dural and headed north from Wisemans Ferry and on to Bucketty, Wollombi, Maitland and finally Newcastle.

Richard Wiseman was given land at Wollombi but also worked on large sheep runs as far north as Tamworth, Armidale and Inverell. In 1859 Richards daughter, Sarah Sophia Wiseman (1835-1869) married Thomas Harvey Stone (1831-1897). Stone was born in Ireland and came to Berrima as a ten-year-old with his parents, the Reverend William Stone and Susan Pitt Johnson. There is a story in this blog on that family – the Reverend and his wife are my 3rd great grandparents and Thomas Harvey Stone was my 3rd great uncle. However, I digress.

Alexander Campbell, also a scotsman settled in the area and is the person who named Inverell. In a curious case of serendipity, Inverell is a Gaelic word meaning ‘the meeting-place of the swans’, which were apparently numerous in the 1830’s. Australia unlike the rest of the world had no white swans, they were all black and as such were a great curiosity.

Was William Swan Jnr., a man moved by such romanticism as living in an area that had swans in abundance? Or was he a sporting Nostradamus who could see that a greater sporting force would emerge that bore a great resemblance to Gaelic football?

Campbell’s property still exists, albeit greatly reduced to the north of the town. By 1861 the population of Inverell had reached 177. The tin discoveries in the area were sparked by a find at Elsmore, 14 km to the east and, by 1875, 500 men were employed at the Inverell mine, including many Chinese.

The life of my 2nd great grandfather, William Swan Jnr. remains a tragic mystery. We know almost nothing of his life in Sydney. He was 15 years old when his mother died, and as the eldest child, was presumably still living at home and helping with the day-to-day family and home life. He was also most likely to be working with his father, learning the tinsmith trade, delivering finished and/or repaired goods and developing his skills so that he could contribute to his family’s well-being. His half-brother, John Cain, two years older than William Jnr., may have had a similar upbringing in learning the trade. John Cain was obviously established in the Inverell region by 1874 when he married Mary Erwin. Their first child, a son, also John was born in August 1873 in Inverell.

John Cain may have been encouraged to venture north when tin ore was first discovered and being mined, enabling the father and son Swan combination to work in a more profitable manner. The tinsmith work would have been conducted inside the house and when William Jnr. was a competent tinsmith, he too may have been encouraged to seek greener pastures; there were two more brothers, Thomas Cormick Swan (1858-1943) and Aden/Haydon Swan (1863-1933) becoming old enough to work with their father in the tinsmith trade.

The trade of a tinsmith, or tinker, also encompassed some of the work skills that we now completely associate with a plumber. Pipes to allow both water and sewage to flow were initially terracotta or bricks, and there were many problems associated with this type of technology, particularly in a major city that was growing at a rapid rate. New technology was tin or copper piping – and the tinsmiths were the tradesfolk who could make them. However, in a growing city like Sydney the major pipes to bring in water and get rid of effluent were large cast iron pipes and required a level of manufacturing technology which was not compatible with the small home-based tinsmiths. The tinsmiths provided domestic piping such as downpipes, guttering, pumps and waste containers – the products now associated with plumbers.

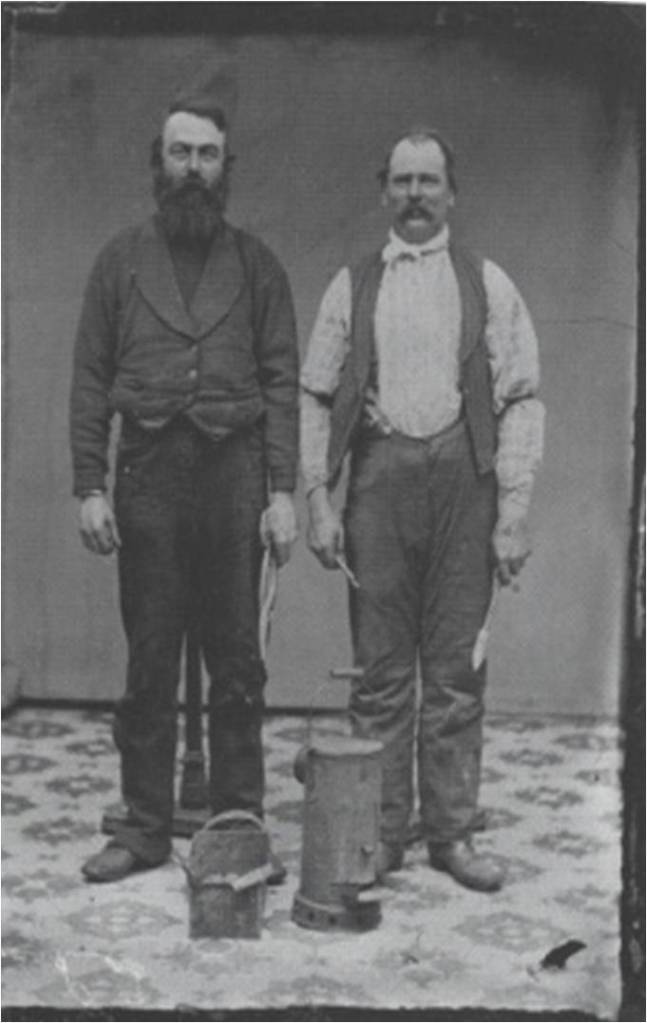

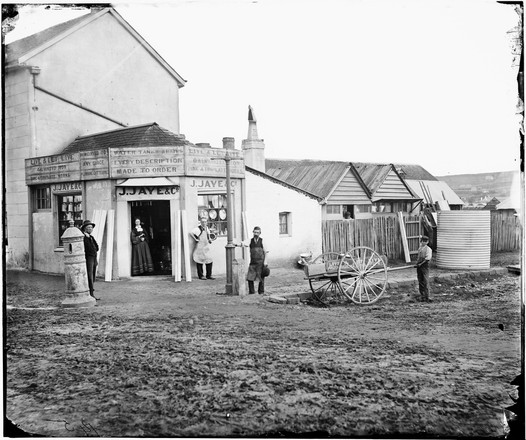

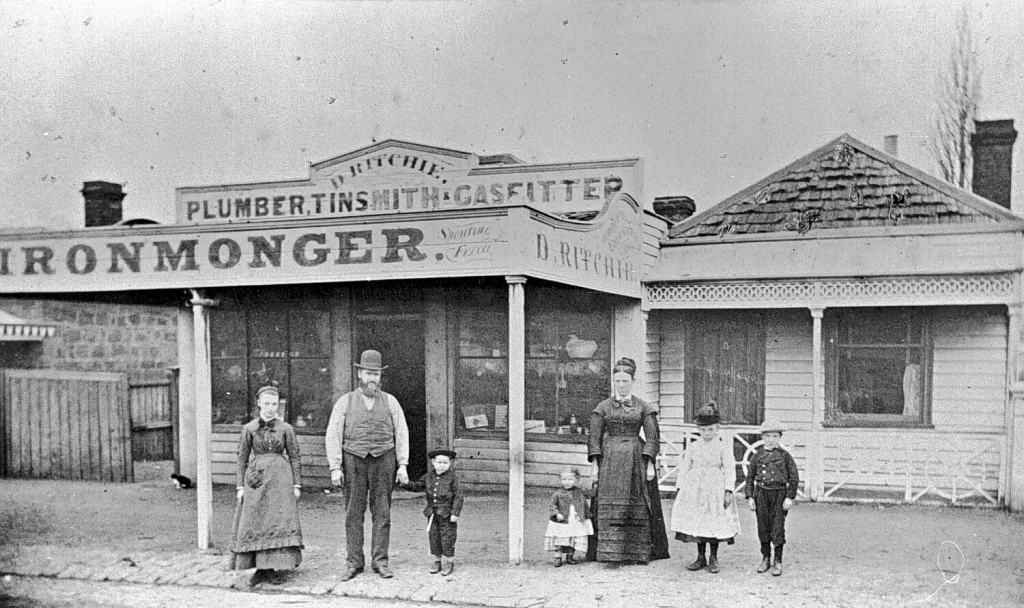

This gallery of old photograph does not contain anything sourced from either the Swan or Cain families. They are just generic photos of tools, products, goods and shops utilised by tinsmiths in Australia in the second half of the 19th century.

During the second half of the 19th century, sewage was a huge problem for Sydney with the first outfall into the harbour installed in the 1850’s right where the Opera House is now. By 1875, this single pipe had been replaced with another half a dozen around the city and Darling Harbour, each carrying untreated waste into the water. Sydney city officials thought that currents would send the muck out to sea, but instead the city was faced with banks of stench-filled raw effluent mud that ebbed and flowed with the tides. What left via the harbour well and truly came back with the changing tides! With this effluent came the bugs, flies and a diseased rodent population. In 1875 there was a major outbreak of typhoid fever which was reported by newspapers around the world. Scarlet fever and smallpox epidemics were rife during the 1880’s and 1890’s. Over time sewage collection and disposal became a system of “night soil” collection. Full sealed pans would be taken away on carts and clean deodorised ones left in their place.

The supply of water for Sydney was also a problem, with droughts experienced many times during this same period. I found no evidence that the Swans or the Cains were involved in this “branch” of tin smithing, perhaps mining the ore hundreds of miles from Sydney Harbour was a much more attractive proposition for the young men in the family.

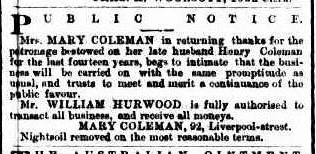

William Hurwood (1838-1916), the husband of Mary Ann Cain (1845-1886) who the eldest daughter of Bessie and Thomas Cain is mentioned in a “Public Notice” published as an advertisement in the Sydney Morning Herald on the 2nd of March 1871. It seems that he is working as a manager for Mary Coleman in the business of removing nightsoil. Hurwood strikes me as a most capable and enterprising fellow, greatly assisting the family in organising funerals, placing advertisements in newspapers and in the 1890’s he has established himself as a photographer, working from 117 Liverpool Street. The Hurwoods lived on Dixon Street, which was along the southwestern edge of Darling harbour in the 1860’s. That part of the harbour has long been reclaimed and is now where the Chinese Gardens of Friendship is located at Tumbalong Park.

William Swan Jnr’s wife, Jane Emily Hill, was born in Inverell in 1867, one of nine children to English migrants, George Hill (1831-1876) and his wife, Mary Ann Coombs (1846-1927) who were from respectively, Devon and Wiltshire. Mary Ann Coomb’s life illustrates how hard early settlers endured the trials of the colony. After nine children, her first husband, George Hill died from a fall down a mineshaft; she married James William Brown and had five more children. After Brown’s death, she married a Richard Morris and had another child; then in 1911 after Morris’s death, Mary Ann married William Woolley – four husbands, 15 children.

William and Jane had two more children: William Swan (1886-1911) born in Tingha (halfway between Inverell and Bundarra), and Betsy Ellen Swan (1888-1984) who was born in Inverell on the 10th of June 1888. Tragically, William Swan (1854-1887) had died at the Prince Alfred Hospital in Camperdown at the beginning of November 1887 from “hydatid tumours of the abdomen” which we now term “a parasitic cyst, also called a hydatid cyst, that develops within the abdominal cavity, most commonly in the liver, caused by the larval stage of the tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus”.

Jane was only a few weeks pregnant with Betsy Ellen when William died.

After William Swan’s death, Jane (Hill) Swan married Joseph Johnson (1870-1939) and they decided to “keep” the eldest and youngest of her children fathered by William Swan. Louisa May and William were fostered out and Jane had eight children to Joseph over the next 15 years.

Louisa May appears to have survived her fostered years and at the age of 15, she married Caleb Francis Vacchini in Paddington, Sydney early January 1900. Her younger brother, William suffered badly from his fostering and died in 1911, 24 years old and unmarried.

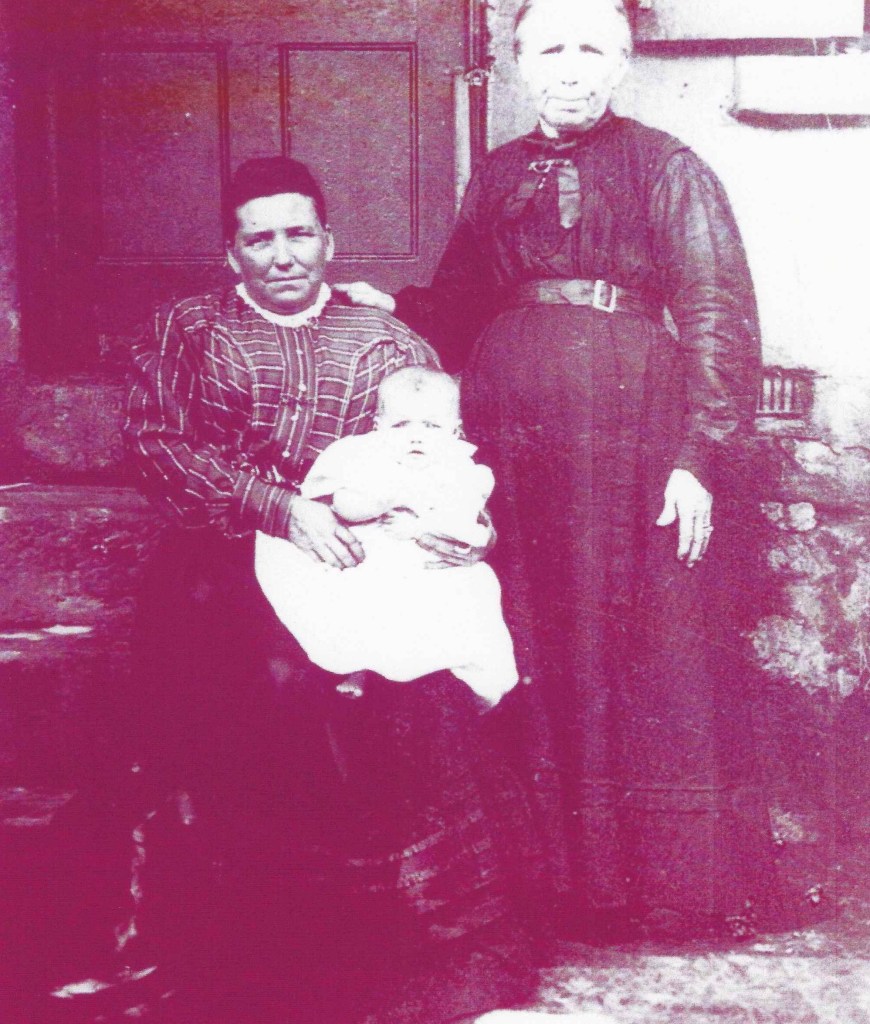

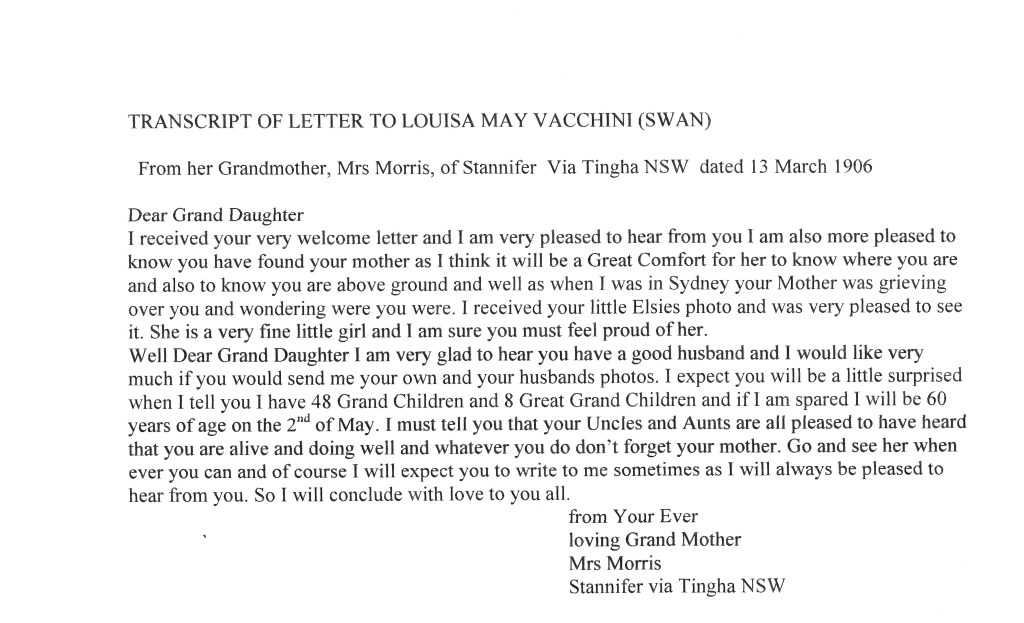

We have a letter to Louisa May written by her grandmother Mary Ann Coombs (the one who had four husbands!) in 1906. You’ll be glad to hear that Louisa May and Caleb had a very happy marriage of almost 50 years.

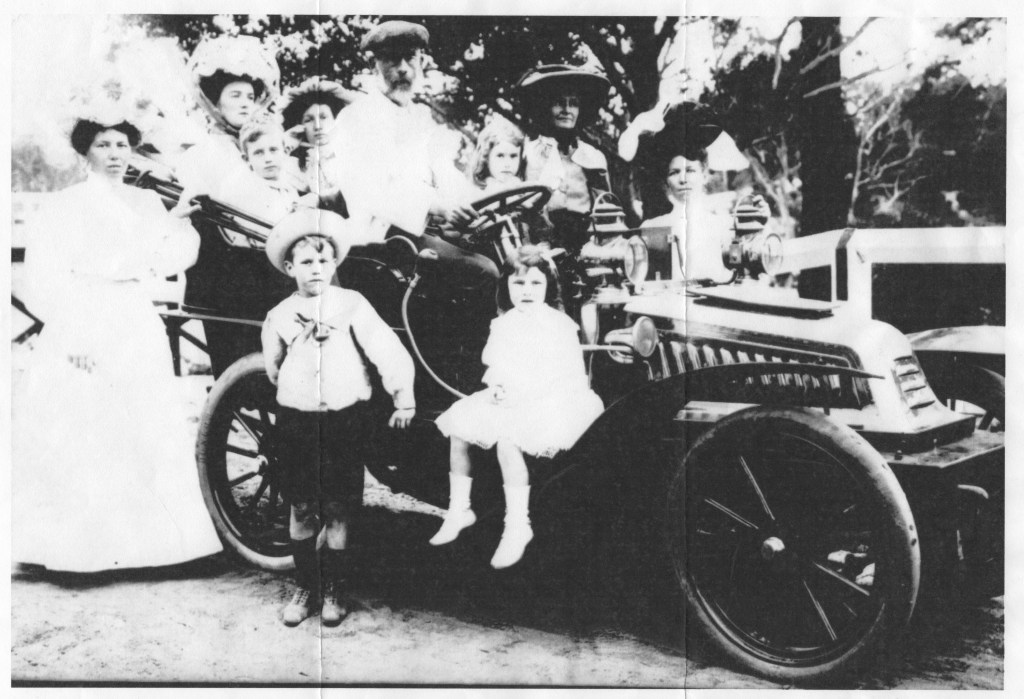

Betsy is on the extreme left.

Back in Sydney, how did William Swan Snr. fare?

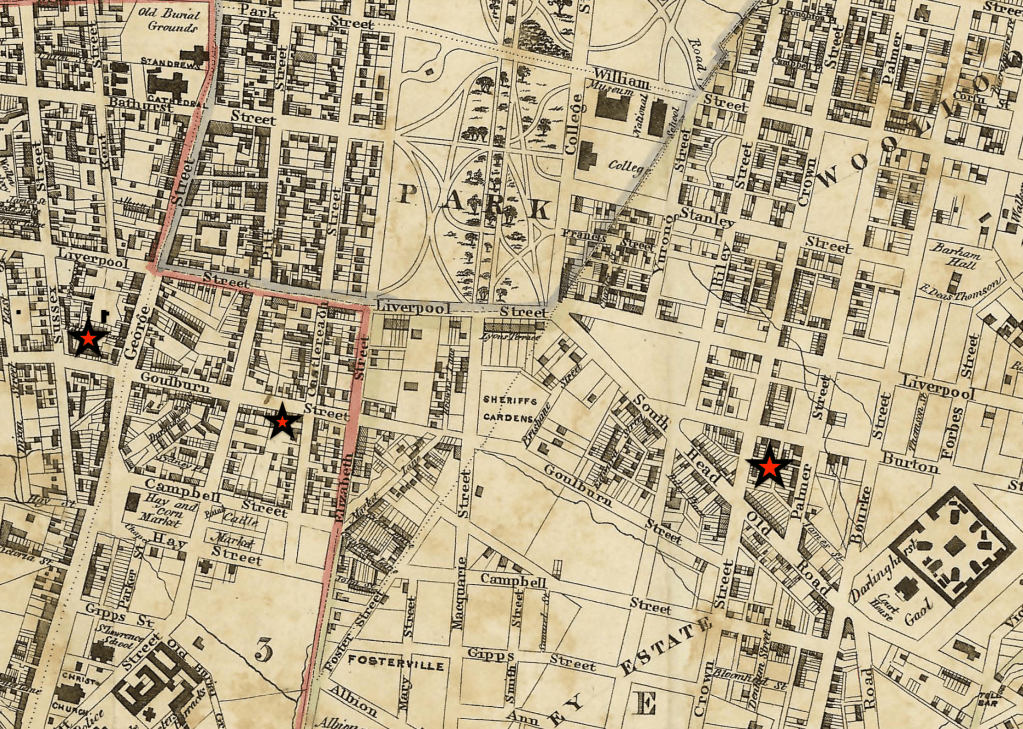

After Bessie’s death in 1869 he continued to ply his trade as a tinsmith, living in the same part of Sydney that they had moved to from West Maitland in 1861/1862. For more than thirty years he was in a number of different places, all very close to one another in a commercial area along Goulburn Street, eventually living in Woolloomooloo, which was once a desirable bayside address east of central Sydney. However, as Sydney expanded and water and sewage problems caused sickness, the area grew more congested and grimier, the wharves expanded to facilitate increased trade and transportation and the boarding houses and pubs gave refuge to larrikin gangs and petty criminals. William Swan Snr. did not live in a very nice part of the ever-growing Sydney in the late 1800’s.

We know very little about my 3rd great grandfather and the manner in which he plied his tinsmith trade.

Tin smithing and copper working used common skills with the equipment used to carry out both trades being almost identical. “Tinplate” is simply iron coated with tin. Products made by tinsmiths ranged from needle cases and candle moulds to stovepipes and guttering. A high proportion of goods made for sale would have been domestic items such as cans, tins and pans of all types, tankards, candlesticks, lanterns, candle safes and tea and coffee pots. Similar items were produced from sheet zinc, the exception being vessels for holding food or drink, for which zinc was not used. The most common type of utensil produced was a container, ranging from small cups known as “pongers” to various pots, saucepans, and jugs. These served multiple purposes: for people to drink from, for animals to eat and drink from, and for transporting liquids or fuel. In addition to containers, lamps and candleholders tinsmiths crafted children’s toys, such as whistles. Tin was also used to create musical instruments, including the tin whistle which Irish folk saw as an integral part of their music.

Tinsmiths such as William Swan in Sydney had three distinct outlets for their work. Firstly, they sold the goods they produced direct to the public on a retail basis from their workshops. Secondly, they could supply local ironmongers or general stores with their wares and thirdly, they worked piece-meal for local firms. Additionally, they would repair vessels that had holes by welding and brazing. From 1863 until his death in 1895 William Swan lived along Goulburn Street in Sydney, just north of what was then “Haymarket” and “cattle market”. The services directories that were published during those years indicate that he moved from west (just near Dixon’s Wharf) to east (Woolloomooloo). He seemed to be continually moving to the “seedier side of town.” There is no documentation to show that he was anything but self-employed; and with sons to learn the trade, he probably enjoyed that methodology.

We are not sure if he maintained a close relationship with his children or even cared for them after Bessie’s death. He probably did teach his sons and step-sons his trade and gave them some insight into the pros and cons of mining tin ore. It is also probable that the family structures of Bessie’s daughters from her marriage to Thomas Cain, Mary Anne Hurwood and Sarah Martin; along with his eldest daughter, Letitia, were able to either assist or be primarily responsible for the younger children’s welfare. Letitia was only 13 when Bessie died; Elizabeth a two-year-old infant.

There are more than 100 trees on Ancestry that have some reference to “our” William Swan (1820-1895) and his parents, William Swan and Letitia Long who were probably English. The common wisdom appears that the parents both died about 1824/5 in Quebec which begs the questions: how and why did they go to Quebec; who took care of the 5-year-old William when his parents died and how did he get to Sydney by 1853?

There is certainly no shortage of conflicting possible stories and associated ships regarding William Swan’s arrival into Australia.

Some that stand out but have no verification are:

The “Marquis of Hastings” arriving in 1841 from Abbington.

The “William Abrams” arriving in 1841 from Greenock.

As a convict on the “Aurora” arriving in 1833 from Cambridge.

The “Emigrant” arriving in 1853 from Sunderland.

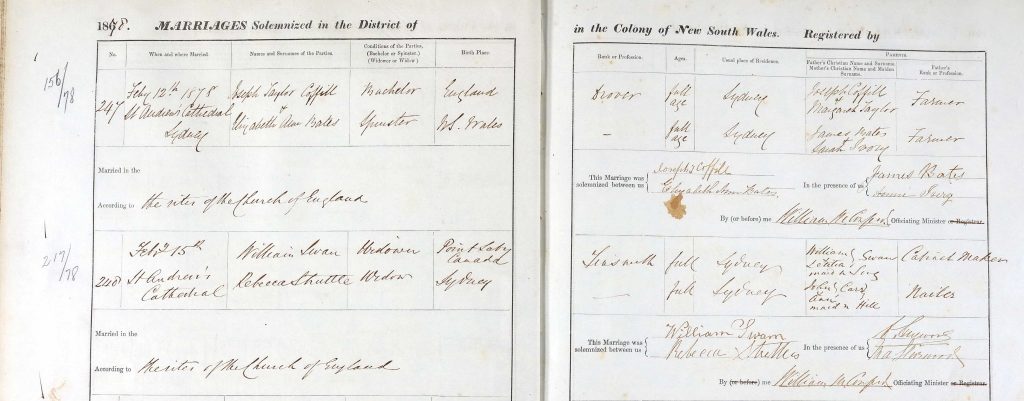

William Swan Snr’s second Australian marriage certificate provides more information.

The marriage was on the 15th of February 1878 at St. Andrews Cathedral, next door to the Sydney Town Hall. William married a Rebecca (Carr) Strettle and the document states that he was a widower, a tinsmith; that his father was William Swan, a cabinet maker and mother Letitia Long; and that he was born in Point Levy, Canada. It also states that Rebecca was a widow, born in Sydney, her father was John Carr, a nailer and her mother was Ann Hill.

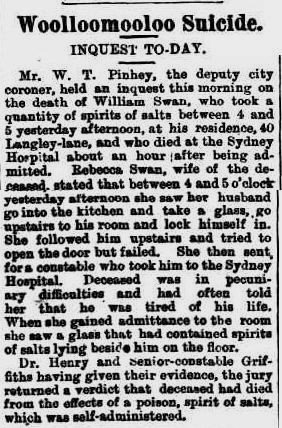

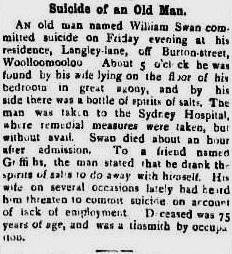

William Swan Snr. did not have a pleasant end to his life. Newspapers reporting on his death were not sympathetic to his age, his demeanour nor his capabilities.

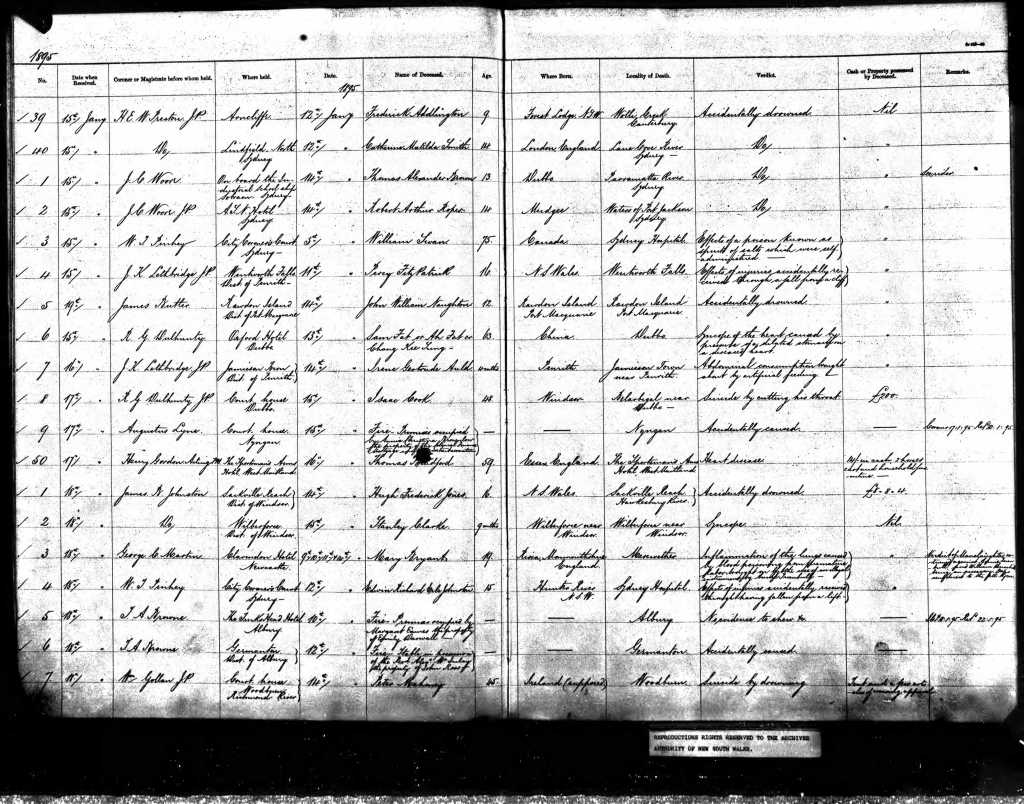

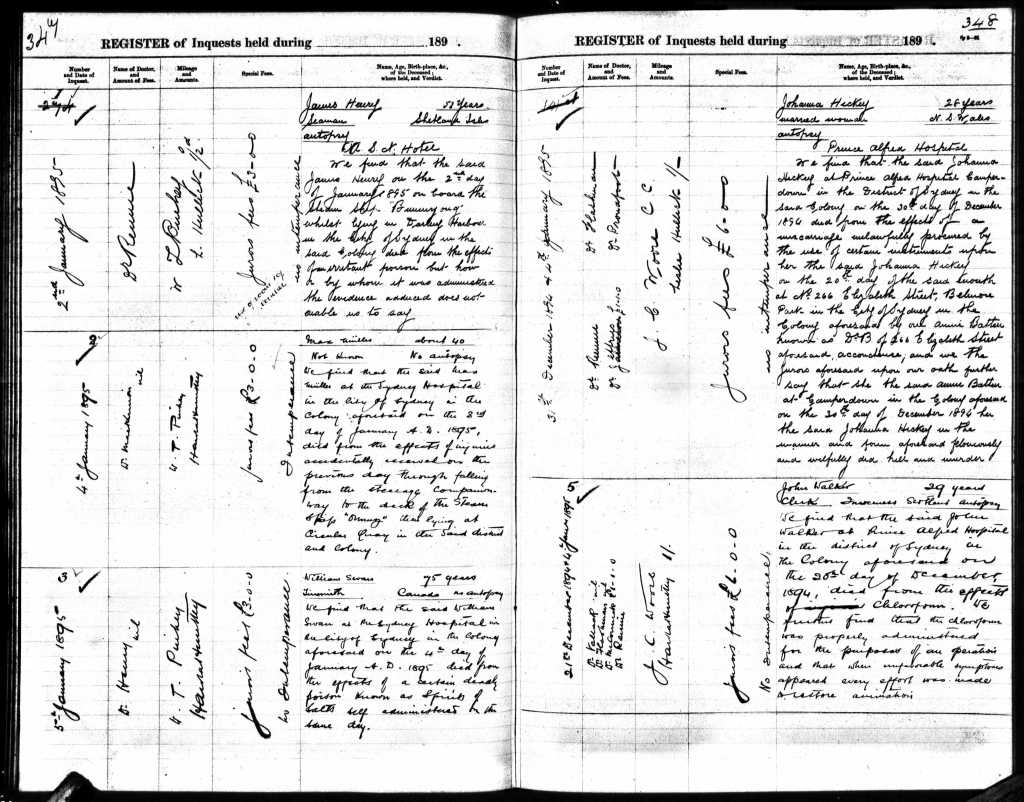

The inquest/coroner’s report on his death states that William Swan, a tinsmith, 75 years old, born in Canada died on the 4th of January 1895 from the effects of a certain deadly poison known as Spirits of Salts self-administered on the same day.

His death was reported in the press of the day and we do have the coroner’s report and inquest into his death.

It was a tough life in the colony during the life and times of the Sydney Swans. Infant mortality was rife; sewage and droughts took their toll; discovery of gold produced a boom that was followed by a major depression. However, for a lot of people it was an opportunity to shape their own destiny.

As with any period of history in any part of the world it is perspective that determines good from bad; wealth from poverty; and joy from sorrow.

Leave a comment