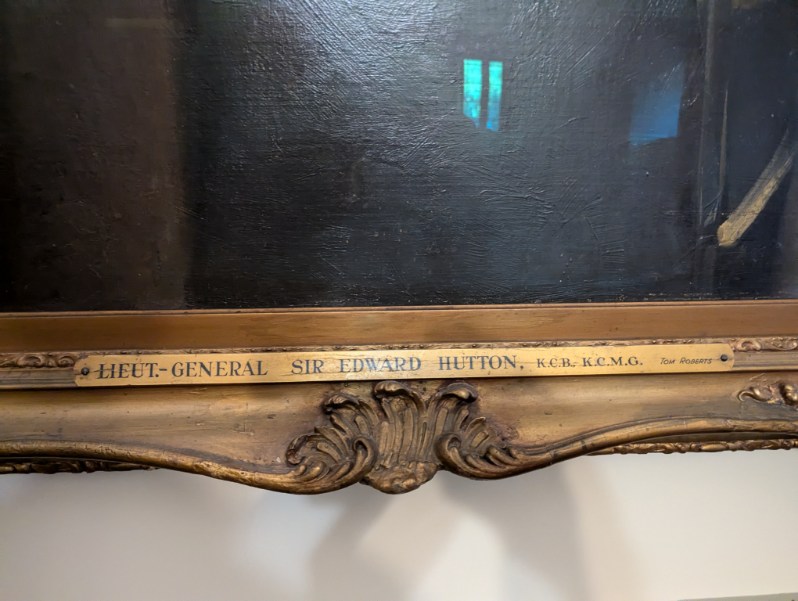

On the last day of our little trip to Canberra we were invited by the Major to visit the Officers’ Mess in Duntroon for a few libations before our last dinner in the nation’s capital. The Major gave a great tour of the complex, pointing out various buildings and their utilisation during a recruits training. As we chatted in the Mess, I noticed a portrait which featured on the wall behind our chairs.

It was an oil painting by Tom Roberts of a very famous military figure: Lieutenant-General Sir Edward Thomas Henry Hutton, KCB, KCMG, DL, FRGS a British military commander, who pioneered the use of mounted infantry in the British Army and later commanded the Canadian Militia and the Australian Army. I “knew” this man as my great grandfather had given his eldest son the name Hutton as his middle name in honour and recognition of the esteem in which he held the General.

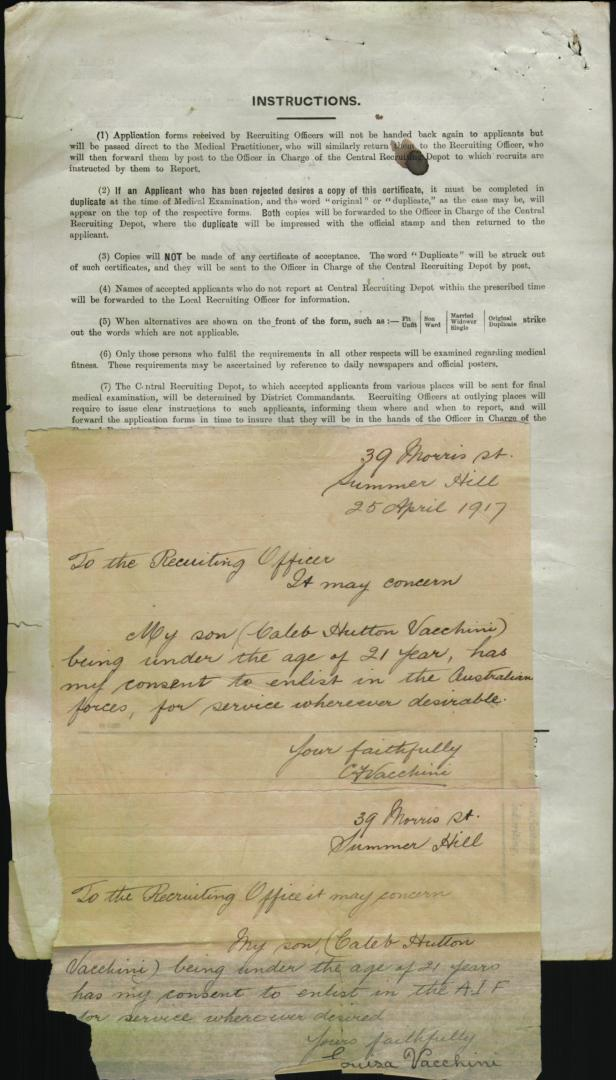

My grandfather was Caleb Hutton Vacchini who participated in WWI as a teenager.

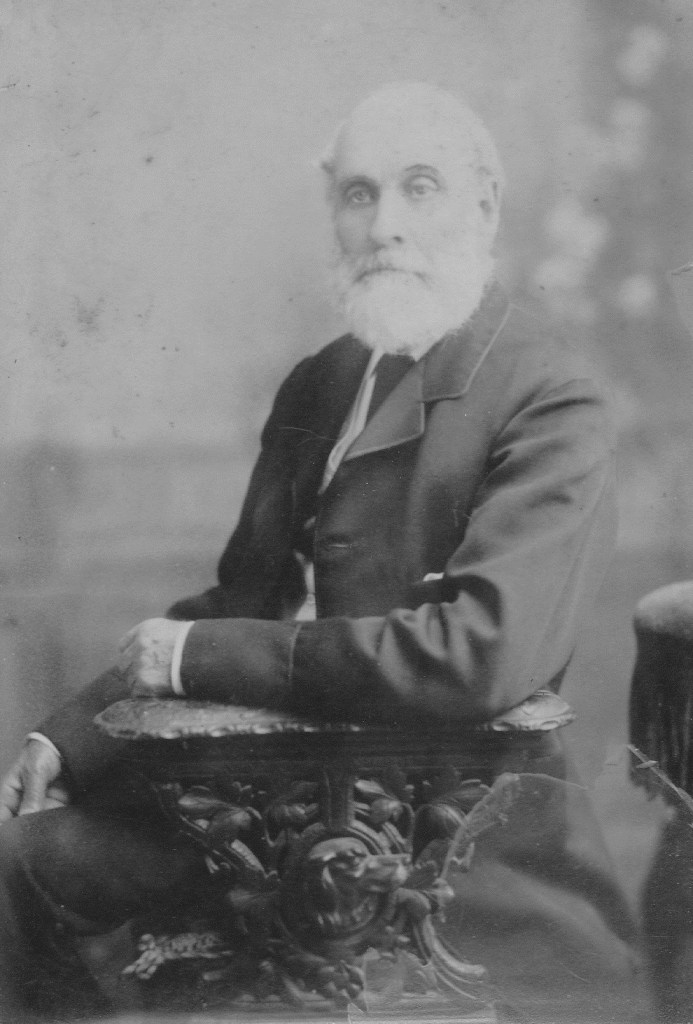

My great grandfather was Caleb Francis Vacchini, a horseman of great skill and a Sergeant with the 1st New South Wales Mounted Rifles who served in South Africa during the 2nd Boer War. Sergeant Vacchini was part of strong brigade of mounted infantry made up of Australian, New Zealand, Canadian and British units led with great distinction by our Major General Hutton.

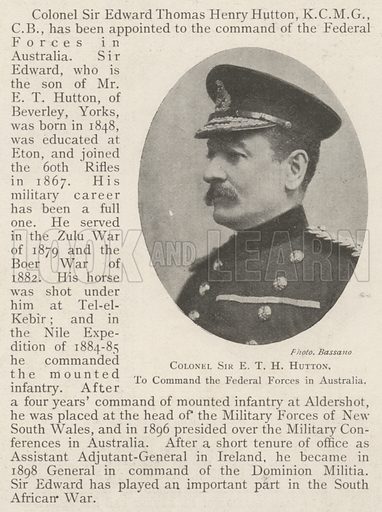

Sir Edward Thomas Henry Hutton was born on the 6th December 1848 at Torquay, Devon, England, the only son of Colonel Sir Edward Thomas Hutton and his wife Jacintha Charlotte, née Eyre. He was to become a rising star in the British Military, both with his service and with his family affiliations.

He was the stepson of General Sir Arthur Lawrence and the famous swordsman Alfred Hutton (1839–1910) was his uncle. He was educated at Eton College, where he was given the nickname “Curly” leaving in 1867 and taking a commission in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. Promotion to lieutenant came in 1871, and from 1873 to 1877 he served as Adjutant of the 4th Battalion.

He first saw active duty in Africa in 1879, when he served with his regiment in the Anglo-Zulu War, being mentioned in despatches and promoted to captain for his service at the Battle of Gingindlovu. He served with the mounted infantry force in the First Anglo-Boer War of 1880–81, and as a result was appointed to command the mounted infantry in the Anglo-Egyptian of 1882 as a brevet major. He fought around Alexandria and at the Battle of Tel el-Kebir where he had a horse killed underneath him and again was mentioned in despatches. In the Nile Expedition of 1884–85, he was appointed to the staff in command of the mounted infantry.

Hutton had become closely linked with the employment of mounted infantry in the African campaigns and was the army’s leading authority on its use; in 1886, he gave a public lecture calling for a widespread scheme of training and preparing mounted infantry units within the units stationed in Britain. At Aldershot, England, he raised and commanded mounted infantry units in 1888-92, becoming recognized as one of the leading proponents of this form of mobility. In 1889 Hutton was promoted lieutenant-colonel.

On 1 June, at St Paul’s Anglican Church, Knightsbridge, London, he married Eleanor Mary, daughter of Lord Charles Paulet and granddaughter of the marquis of Winchester. His marriage and his appointment as aide-de-camp to Queen Victoria in 1892 afforded him a degree of influence unusual for an officer of his rank.

Promoted colonel in 1892, ‘Curly’ Hutton became commandant of the New South Wales Military Forces with the local rank of major general in 1893. The advent of an able leader committed to military reform and with recent war experience revived the flagging spirit of the New South Wales forces. Hutton inspected units in every part of the colony, addressed public gatherings and brought the army before the community, beginning with a major review in Sydney in July 1893. On one of his inspections, he travelled 680 miles (1094 km) in twenty days including 500 miles (805 km) on horseback. He visited training camps and exercises, delivered lectures to officers, fostered rifle clubs and supported the movement for raising national regiments such as the Irish Rifles.

Valuable as the public side of his work was, Hutton’s reorganization of the New South Wales forces was even more important because it gave the colony an army capable of taking the field as part of a Federal force. Hutton from the start aroused suspicion in some quarters by his outspoken remarks on helping ‘England in her hour of need’. He also vigorously supported the movement for Federal defence; in a speech at Bathurst in January 1894 he advocated one defence policy for the six colonies, a common organization of their forces while preserving their identity, a Federal regiment of artillery and a Federal council of defence.

By this time the political movement for Federation was overtaking the military movement and political leaders were looking for Federation as the necessary preliminary to national defence.

Hutton returned to England in March 1896. By the end of his command Hutton had become an important public figure. A convinced Imperialist, he quickly began to propagate his ideas on Australian defence, addressing members of parliament on the topic and the Aldershot Military Society on ‘Our comrades of Greater Britain’. In that address the concept of the Australian soon to be popularised by Charles Bean was already discernible:

‘The Australian is a born horseman. With his long, lean muscular thighs he is more at home on a horse than on his feet, and is never seen to a greater advantage than when mounted and riding across bush or a difficult country … Fine horsemen, hardy, self-reliant, and excellent marksmen, they are the beau ideal of Mounted Riflemen … Accustomed to shift for themselves in the Australian bush, and under the most trying conditions of heat and cold, they would thrive where soldiers unaccustomed to bush life would die’.

This address was widely reported in Australia as well as in Britain and he could have been describing my great grandfather, Caleb Francis Vacchini.

After a staff appointment in Ireland, Hutton went to Canada in 1898 to command the Canadian Militia, a force which presented him with opportunities of reform as far-reaching as those in New South Wales. His aim was to build a national army for Canada which would also be available to serve abroad. Unwisely, he became involved in Canadian politics; his efforts to pursue a military policy of his own became known to the Canadian government and his public speeches at the time of the South African War in 1899, with other devious activities, led to a crisis in which he was forced to resign. He returned to his true sphere, serving in South Africa where, as a major general, he commanded a strong brigade of mounted infantry with great distinction in the advance to Pretoria. His brigade included Australian, New Zealand, Canadian and British units and he chose his staff largely from the colonial forces. His letters reveal his enthusiasm for the colonial citizen soldier and his awareness of a special responsibility in such a command which seemed to him as much political and Imperial as military. For his services in South Africa, he was appointed Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG) in 1900.

In late November 1901 it was announced that Hutton would become the first General Officer Commanding the Australian Military Forces. He was recommended by Field Marshal Lord Roberts after several other officers had refused or were rejected by the government. He arrived in Australia in January 1902, and his main task became that of transforming six colonial forces into one national Australian Army. In the role of commander-in-chief Hutton was the designer and maker of Australia’s first post-Federation army.

For all his soldierly qualities, professionalism, experience and zeal, Hutton was devoid of the tact which might have eased his relations with the ministers whom, too often, he despised. However much he was disliked and distrusted by politicians, he was held in affection and admiration within the army and he left his mark on those who were to lead the Australian Imperial Force.

Hutton resigned as GOC Australian Military Force at the end of 1904.

On his return to the United Kingdom he was given charge of administration in the Eastern Command and made G.O.C. of the 3rd British Division. At last in November 1907 he was promoted lieutenant-general on the eve of retirement. He was appointed K.C.B. in 1912. A riding accident in 1915 brought about his final retirement.

He died on 4 August 1923 and was buried with full military honours at Lyne near his home at Chertsey, Surrey. He was survived by his wife; they had no children.

It became very clear in pursuing his biography that Hutton was a very strong force with great courage and that he performed a masterly role in the reorganising and leading the formation of the Australian Army.

I’d like to recount a store of well-oiled anecdotes about General Hutton and my great grandfather, Sergeant Caleb Francis Vacchini. Stories that may have included fireside discussions and later actions by both men during the 2nd Boer War. Riding horseback together as General Hutton reached out to connect personally with as many Light Horse Infantry as he could. Sadly, although these things may have happened, I have no record of such.

Caleb Francis Vacchini (1870-1947) was the step-son of an early pioneer of this country, Mr James Hooke. James Hooke had left his native Devonshire, England for Sydney in 1838, only nineteen years of age. He explored extensively in both New South Wales and Queensland, notably on the Clarence River where he was one of the first white men to set foot. He owned and managed both sheep and cattle stations with varying success and was considered an expert in valuing property. For many years he was headquartered at “Ranger’s Valley” in Glen Innes as a general manager for a farming and property company that was based in Sydney. Hooke settled in Picton, New South Wales in 1880 and developed a house and property called “Hillgrove”. He would have passed on much of his knowledge and experience to Caleb Francis Vacchini, who in his teens left Picton to become a jackaroo on a sheep station somewhere in NSW.

The Oaks Historical Society provided the following information:

“CALEB FRANCIS VACCHINI – Caleb was born in 1870 at Sydney to an Italian Father and English Mother. His father died when he was very young and his mother took the family to Picton to live with her aunt and uncle. The aunt died and Caleb’s mother became housekeeper to her uncle, by marriage, and then married him. The uncle, Mr James Hooke, a prominent citizen of the town raised the children including Caleb as his own.

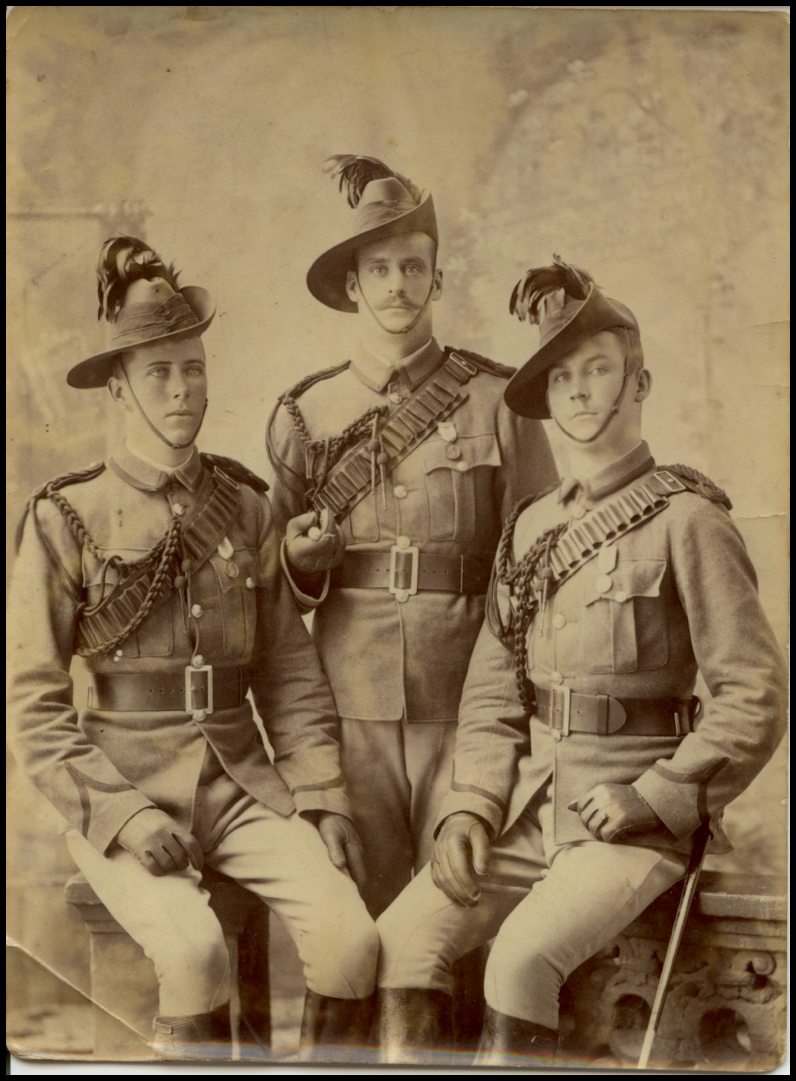

Caleb was sent to the South West of NSW to learn the art of station operations and hopefully management, but work became scarce and after several years he returned to Picton and worked as a farm labourer. He was prominent in the town as a sportsman, representing at football, where hardly a match passed that he wasn’t praised for his efforts, cricket, cycling and shooting. In the early 1890’a he became a member of the Mounted Rifles and in 1897 was one of three Picton men selected for the Contingent to the Queen Victoria Diamond Jubilee Celebrations. He had a successful tour of England and won a medal for mounted wrestling. In March 1901, he sailed as a Sergeant with the 1stMounted Rifles for South Africa, returning on the 1st May 1902. He returned to work as a labourer and continued his sporting achievements. For some years he was secretary of the Rifle Club and won a number of shoots including the club championship. Caleb became the Inspector of Nuisances for the Local Council but with a growing family, (he had married prior to embarkation for South Africa) he decided to try the city. The family moved away from Picton in 1913. Caleb fulfilled a secret ambition and became self taught carpenter and amongst other buildings, erected his own home in Northbridge. He worked into his seventies and unfortunately died as a result of a fall from a building in 1947 at the age of 77 years.”

This would appear to be the type of Australian soldier that General Hutton referred to as his ideal. It is worth repeating – ‘The Australian is a born horseman. With his long, lean muscular thighs he is more at home on a horse than on his feet, and is never seen to a greater advantage than when mounted and riding across bush or a difficult country … Fine horsemen, hardy, self-reliant, and excellent marksmen, they are the beau ideal of Mounted Riflemen … Accustomed to shift for themselves in the Australian bush, and under the most trying conditions of heat and cold, they would thrive where soldiers unaccustomed to bush life would die’.

And it would also appear that General Hutton made quite an impression on the country horseman from Picton, C.F. Vacchini, so much so that he gave his eldest son, Caleb, the middle name “Hutton”.

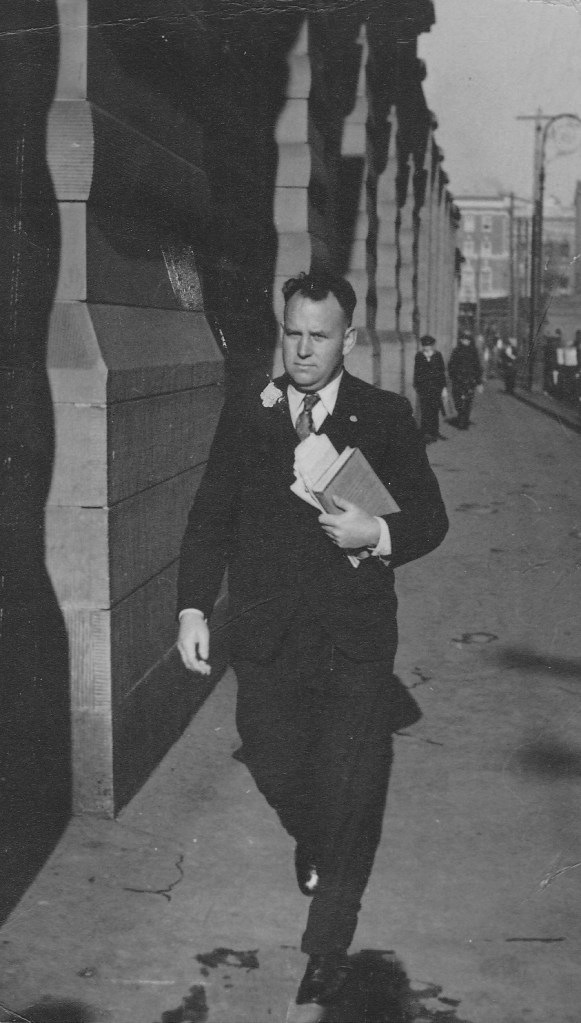

Caleb Hutton Vacchini (1900-1958) was born while his father was serving in the 2nd Boer War. His eldest daughter (my mother, Juli) has these memories

“Dad left school when he was 14 and was apprenticed to a lithographer presumably his artistic talents showed up early. The family were very patriotic, like many at that period- but perhaps also because of Grandad’s involvement in the jubilee and the Boer War. To fight for king and the motherland was expected of young men and indeed they expected it of themselves so that when Dad decided he would enlist – at the age of sixteen – his parents did nothing to stop him, which they could have by refusing to sign the papers and saying he was underage, which of course he was. So off he went to the horrifying experience of trench warfare which completely changed his way of thinking he came back a pacifist, a socialist and a quite militant atheist. He also experienced living among foreigners for the first time, he used to tell us about the habits including the eating habits of ‘the French and the Belgians’ which seemed to him to be very crude compared to what he knew from home. I realised only later that of course the people he was talking about were peasants and were not typical of all the French and Belgians.”

Juli’s younger brother, Ian has similar memories of his father:

“Young Hutton, as he was known (named after his father’s commander, General Hutton in the Boer War, attended Picton Public School and Sunday School at the local Methodist Church. The family moved to Cronulla and he attended Sydney Technical High School until Second Year. In 1917 attempted to enlist but with parents’ permission eventually did. Trained on Salisbury Plains in England and then was in France in trenches (under age) in 1918. Family legend is that he was the only survivor of his platoon, because he visited a medical officer for lump in his throat, which eventually killed him as Thyroid cancer in 1958. His experiences in the war made him a confirmed atheist for the rest of his life.

After the war he worked as a Lithographer with John Sands and studied at the Julian Ashton Art School. From about 1926, he was teacher, then Head Teacher of Introductory Art at East Sydney Technical College, later Senior Lecturer when National Art School was formed. He continued in that position until his death on 18thJanuary 1958.”

Another of Juli’s memories is my favourite:

“While he was away the family moved to Cronulla where they had bought some kind of mixed business so he came home in 1919 to a quite different set of family circumstances. He often told the following story of his homecoming. The family knew when he was coming and Gran had prepared all his favourite food, while Granddad had filled the woodfired copper with gum leaves and branches. Young Fred, aged 8, was deputed to stand at the end of the street and watch for him. As soon as he came in sight he ran home as fast as he could to tell Granddad who lit the fire so that as Dad turned the corner, he could smell the burning gum leaves – he felt he had really come home at last.”

I did not know either my grandfather, Caleb Hutton Vacchini, or my great grandfather, Caleb Francis Vacchini. I understand their shared joy of woodwork, something that my meagre efforts would have been enhanced by their tutelage. I certainly did not know General Hutton and I am not at all comfortable on horseback. A chance encounter with the portrait of the General in the Officer’s Mess at Duntroon, Canberra, courtesy of Major Miles has prompted me to delve into the available resources and set out this little story, complete with some pictures and family background.

~ ~ ~

Leave a comment