INTRODUCTION:

Sarah Miles.

Born in 1824 in Priston, Somerset England and baptised on the 4th July of that year.

Sarah was the ninth child, the third daughter of a Priston farm labourer, John Miles and his wife, Elizabeth Heal who was from nearby Camerton.

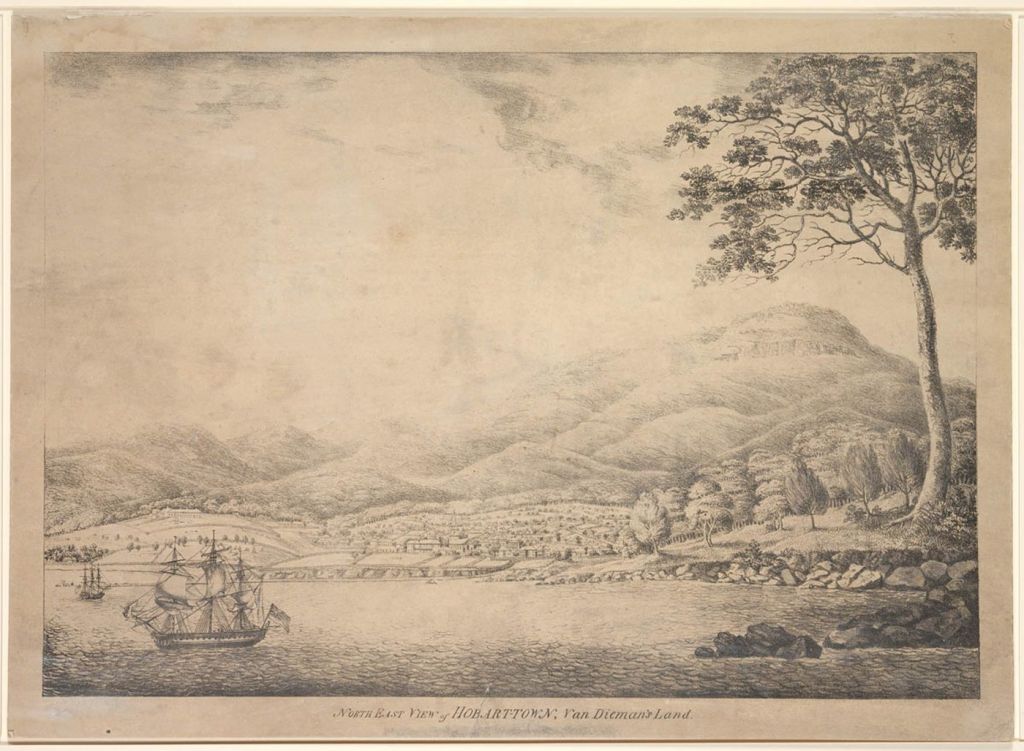

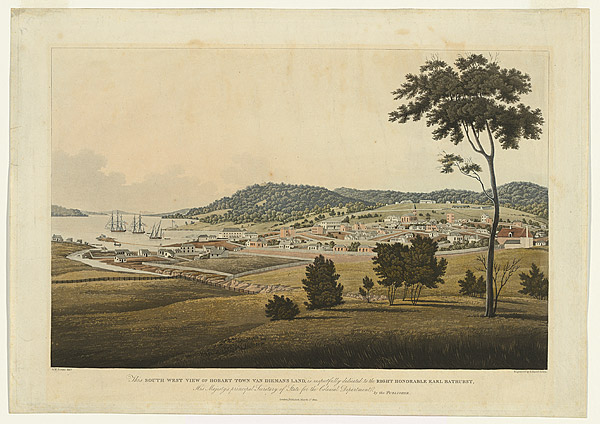

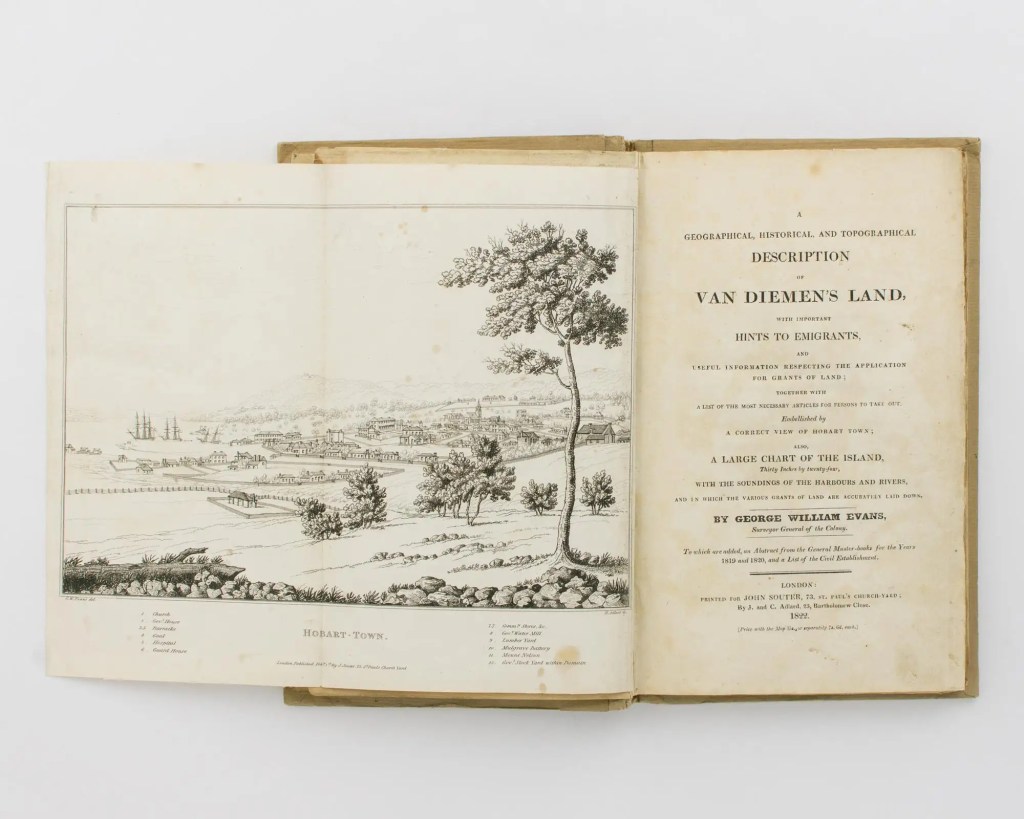

On the morning of the 10th April 1843 Sarah and three accomplices were apprehended for the theft of clothing in Southwark, London, almost 120 miles due east of Priston. Sarah gave a false name to the authorities – Sarah Jones – and on Christmas Day 1843 she arrived by ship in the port of Hobart, a voyage of more than 13,000 miles on the other side of the world. Sarah was transported on the “Woodbridge” along with 204 female convicts, 24 children, 4 male warders and 15 female warders. She had been sentenced to 15 years transportation and it is highly possible none of her family had any clue as to what had happened to her or where she had gone.

In 2018 Robyne Kirsch an Australian direct descendant, one of Sarah Miles/Jones’s 3rd great granddaughters, unravelled exactly what had happened to Sarah.

This is the story of Sarah Miles.

THE FIRST TWENTY YEARS:

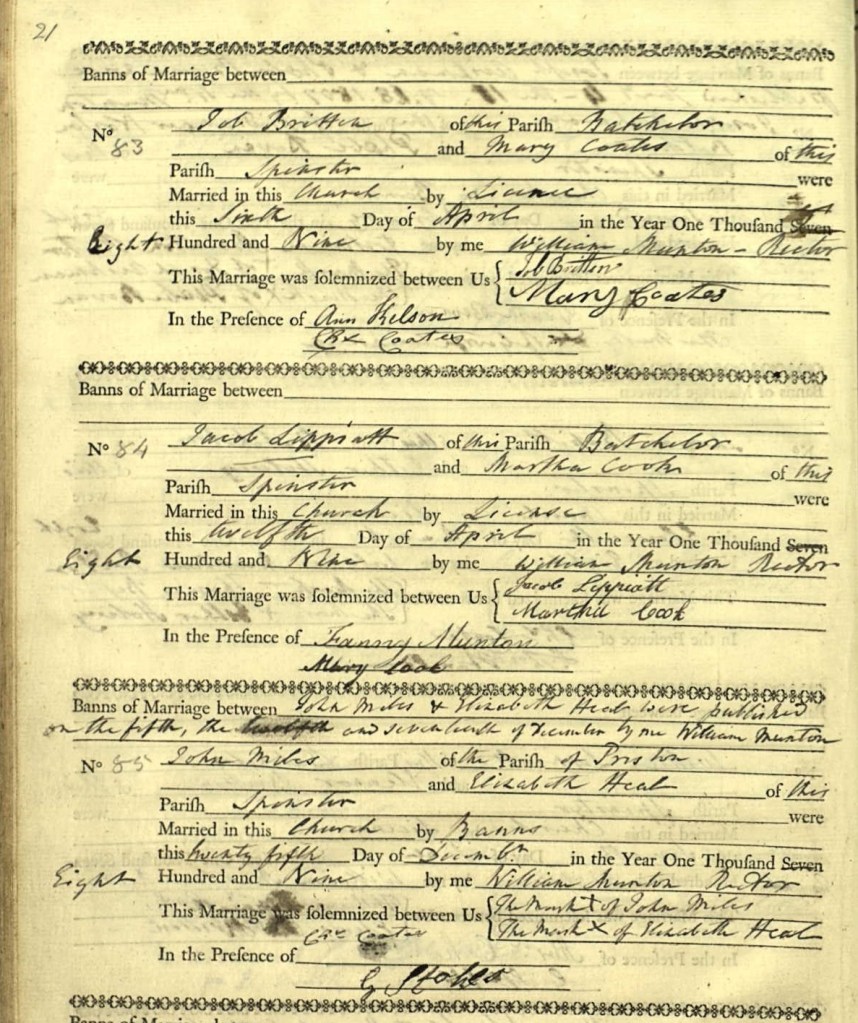

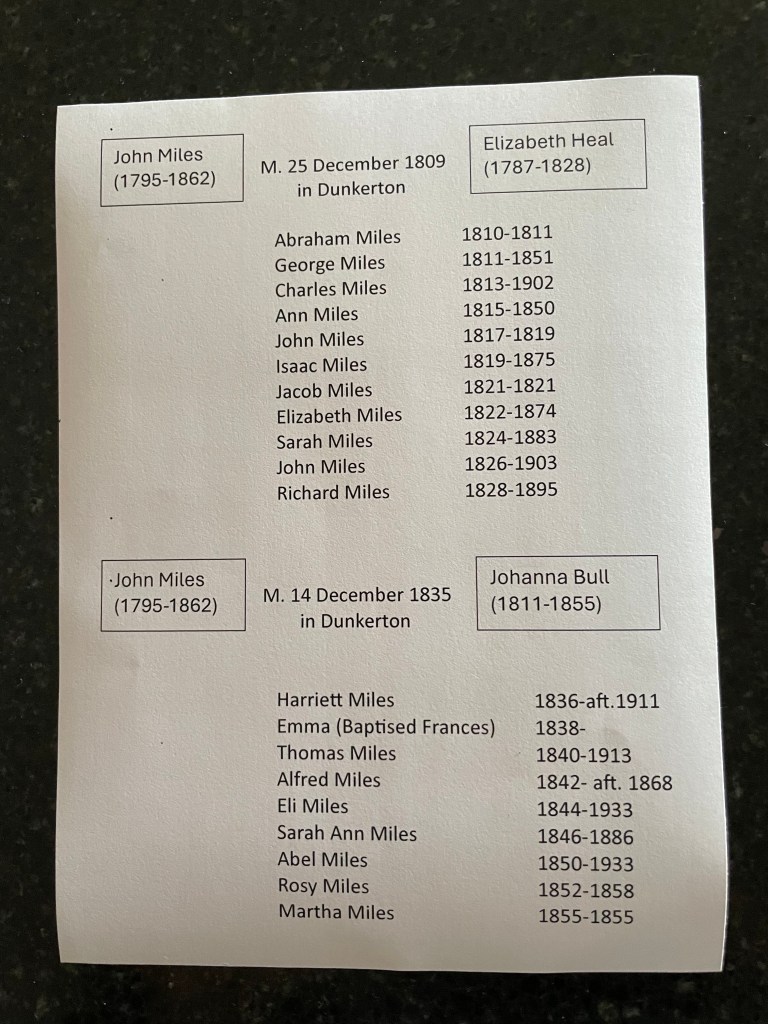

Sarah’s parents were John Miles (1795-1862) from Priston and Elizabeth Heal (1787-1828) from Camerton who were married on Christmas Day, 1809 in the Dunkerton All Saints Church. John and Elizabeth had eleven children, all born and baptised in Priston. Sarah, born in 1824 was the youngest daughter and the ninth child. In the family lineage Sarah Miles was a third great aunt of Vicki’s and the youngest sister of Charles Miles (1813-1902) who migrated to Australia with his wife Mary Weston and their children in 1854. Charles and Mary were Vicki’s 2nd great grandparents.

It is not difficult to question the ages of John and Elizabeth at their marriage, however extensive research does show that John was 15 and Elizabeth was 23, eight years older. Their first-born child, a son named Abraham was baptised on the 27th of May 1810 which suggests that pregnancy preceded marriage. It has also been suggested that Elizabeth may have been pregnant to someone else and that an arrangement was made with John. Elizabeth gave birth to ten more children over the next seventeen years, three who died as infants.

The first child, Abraham, only lived for eleven months; the next, George appears to have lived a single life and was identified in the 1851 census. Charles, the third child, married locally and migrated to Australia with children. Ann, the eldest daughter also married locally but only lived to 35. Another son, John was born in 1817 and died almost two years later.

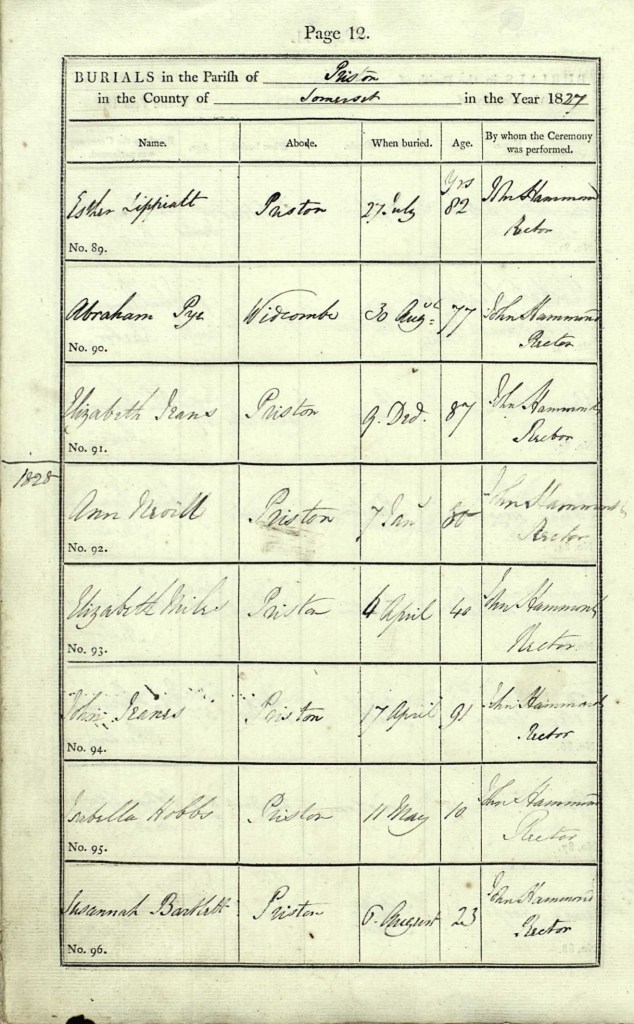

Isaac, born in 1819 lived a wild life which we’ll uncover in more detail later; and another son, Jacob lived for only 19 days at the beginning of 1821. The second daughter, Elizabeth, born in 1822 married a cabinet maker, moved to Bath and had three children. Sarah was next, then two more sons, John born in 1826 did not marry but his life story is known a little; and finally, Richard, the son Elizabeth died giving birth to in May 1828.

John Miles was then the sole parent of eight children ranging in age from seventeen to a newborn. The four-year-old Sarah would have probably been aware of the difficult birth and tragic consequence for her mother. Irrespective of childbirth and infancy deaths, it must have been a very upsetting time, especially for small children. The oldest sons in the family, George (1811-aft.1851) and Charles (1813-1902) would have been working at some farming role in the region and possibly didn’t live with the family.

Four years later, at the end of April 1832, the eldest sister and oldest daughter in the family, Ann Miles (1815-1850) was married in Priston to a local man, George Bishop (abt.1803-aft.1881). Ann, who was 17 when married was probably actively involved in the upbringing of Sarah and her two younger brothers, John and Richard. The only other daughter in the family, Elizabeth (1822-1874) was seven years younger than Ann and two years older than Sarah. Ann and her husband George Bishop named their first born, a daughter, Sarah Bishop (1833-1846). Perhaps to acknowledge and/or to bond with her young aunt, Sarah Miles, who would have been about nine years old.

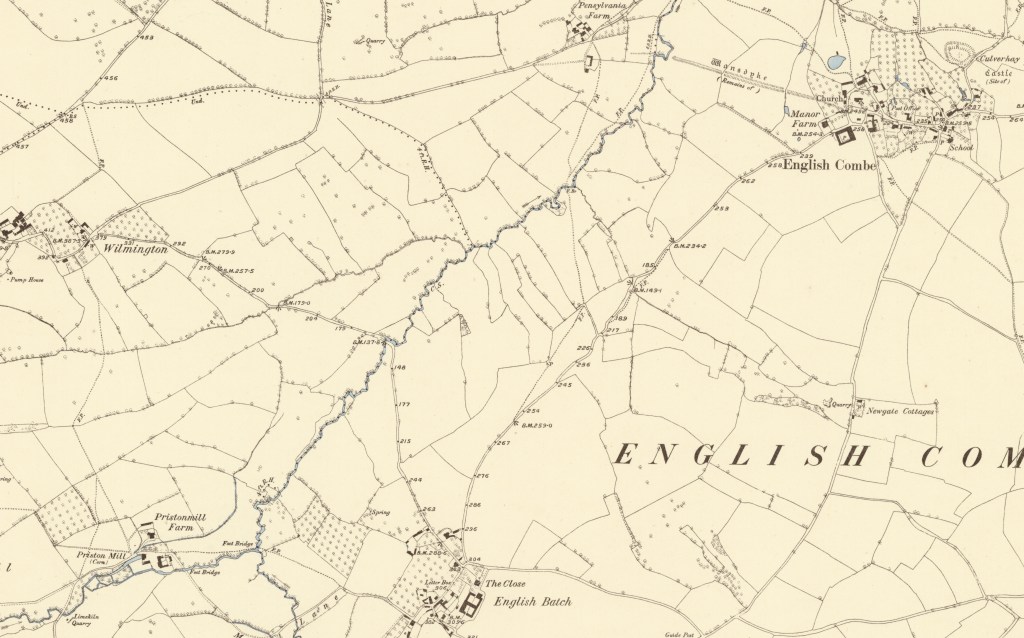

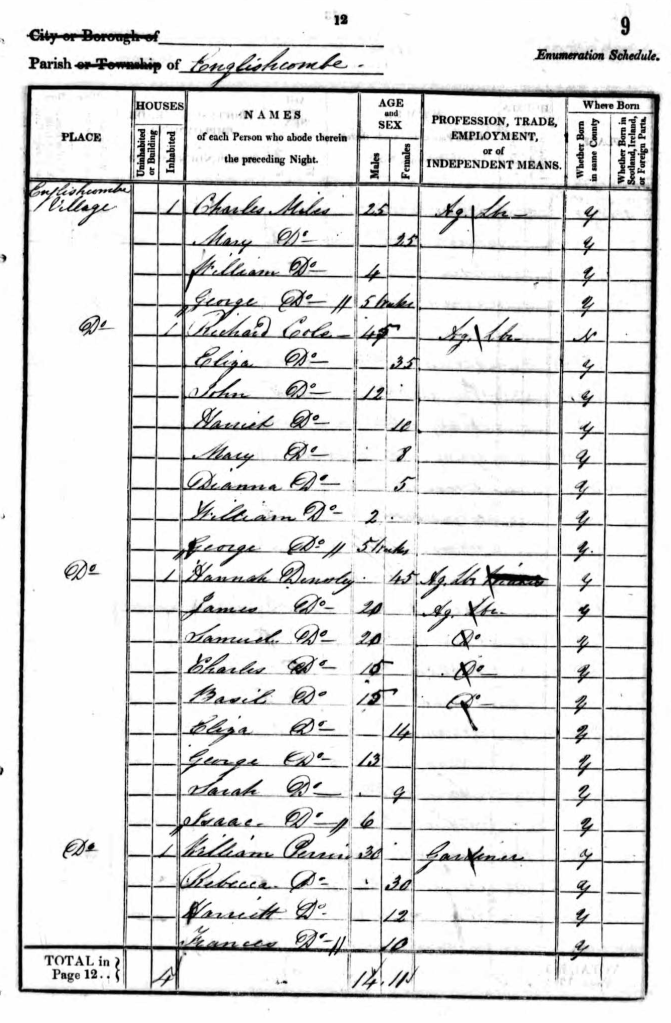

In 1835, when Sarah would have been eleven years old, both her brother, Charles and her father John were married. On the 21st of June 1835 Charles married Mary Weston at St Peter’s Englishcombe. They both may have been working in Englishcombe, a large farm and village that was close to the city of Bath. They had a son, William, born in Englishcombe in 1836 and a daughter, Martha, also born in Englishcombe in 1839 who only lived for a few months.

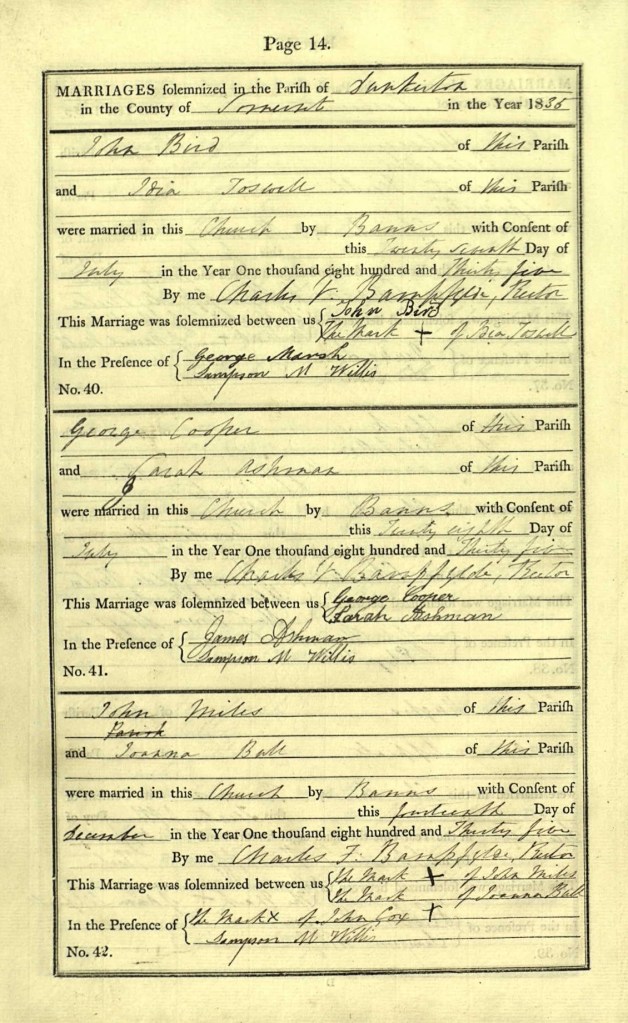

Sarah’s father John married a single woman from the village of Camerton, Johanna Bull (1811-1855) at the Dunkerton All Saints Church on the 14th of December 1835, the same village and church where he married Elizabeth in 1809. It was quite normal for widows and widowers to re-marry soon after the death of a spouse, so a seven-year gap between Elizabeth’s death and John’s marriage to Johanna may have been unusual. For many years the anecdotal Miles family histories in Australia hadn’t “found” the marriage of John Miles and Johanna Bull, nor the true fate of both Sarah and her brothers George, Isaac and John. The three brothers had a myriad of supposed lives and Sarah the daughter of John and Elizabeth Heal was simply noted (correctly) as being born in Priston in 1824 then dying, unmarried (incorrectly) in the coastal village of Breane, about 30 miles west of Priston.

John Miles and his second wife, Johanna Bull had nine children during their twenty year marriage. All were born in Dunkerton except the last child, a daughter Martha who was born in Twerton, just across the river from Bath. The first of these nine children was a daughter, Harriett, born in 1836. She married, had children and had a granddaughter who migrated to Australia with her family in 1913.

Next born, in 1839, was another daughter, Frances, however from the 1841 census onwards she was known as Emma. Five more children expanded John and Johanna’s family; Thomas in 1840, Alfred in 1842, Eli in 1844, Sarah in 1846 and Abel in 1850 all survived infancy and (mostly) married and had children. However, in the first few years of the 1850’s the lives of John and Johanna took a tragic turn when Johanna died during the birth of their ninth child, a daughter Martha early in 1855.

Both wives of John Miles (1795-1862) died either giving birth or soon after giving birth. Unfortunately, and tragically, this was an all-too-common occurrence in the history of humans. In Elizabeth’s case, her eleventh child was a son, Richard Miles (1828-1895) who lived a full life which included fathering nine children. Richard, who had been a miner in Timsbury for much of his working life and his wife Elizabeth Payne retired to the small village of Chipping Sodbury about 15 miles northwest of Bath in the county of Gloucestershire.

In Johanna’s case, her ninth and last child was a daughter, Martha (1855-1855) who was born on the 8th of February in 1855 in Twerton, less than 5 miles from Dunkerton where the family was living. The parish records show that Johanna died in Twerton and was buried in Dunkerton on the 14th of February 1855. The baby Martha was baptised on the 20th of March 1855 and died in September 1855 in Keynsham. She was also buried in Priston.

Keynsham was the part of Bath where the Union Workhouse was situated and census records show that John Miles (1795-1862) was living in the Workhouse for some years after the death of his wife Johanna. Not only did Martha die in Keynsham, (1855), but the next youngest, Rosa Miles (1852-1858) and their father, John Miles (1795-1862) also died in Keynsham. However, they were all buried at Priston, maybe as the extended family and the Church felt it appropriate.

THE CENSUS:

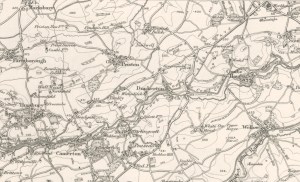

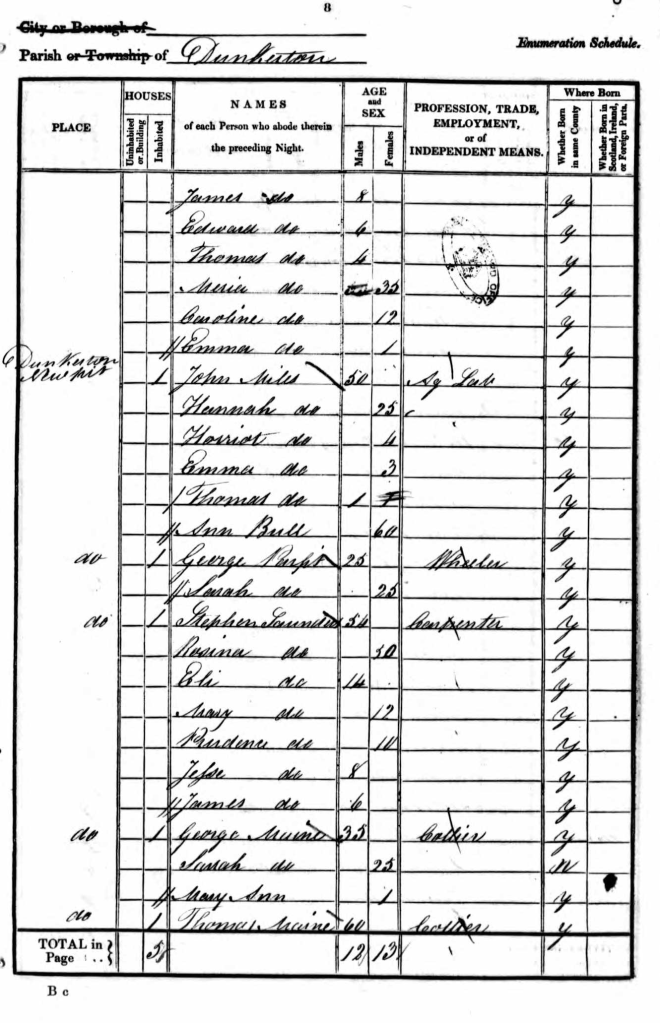

Census records show that family unity was very much present within the Miles family of twice widowed John and his many children. As can be seen by maps of the region, Englishcombe, Camerton, Priston and Dunkerton are all within no more than two miles of each other making contact and support normal. There were many other Miles relatives; aunts, uncles, grandparents and cousins throughout the area, hundreds of people all connected by ancestry to “Old” John Miles and his wife Hannah Wilkins who were married in Priston in 1727.

(written as Hannah) Miles.

The first census was taken in 1841 on the night of June 6th, and subsequent censuses taken every ten years. They are very useful for determining exactly where various family members were living. The censuses can also be used to verify parish and church records for birth, death and marriage; however, they have shown not to be infallible. In many instances it seems that some people were not included in a particular census.

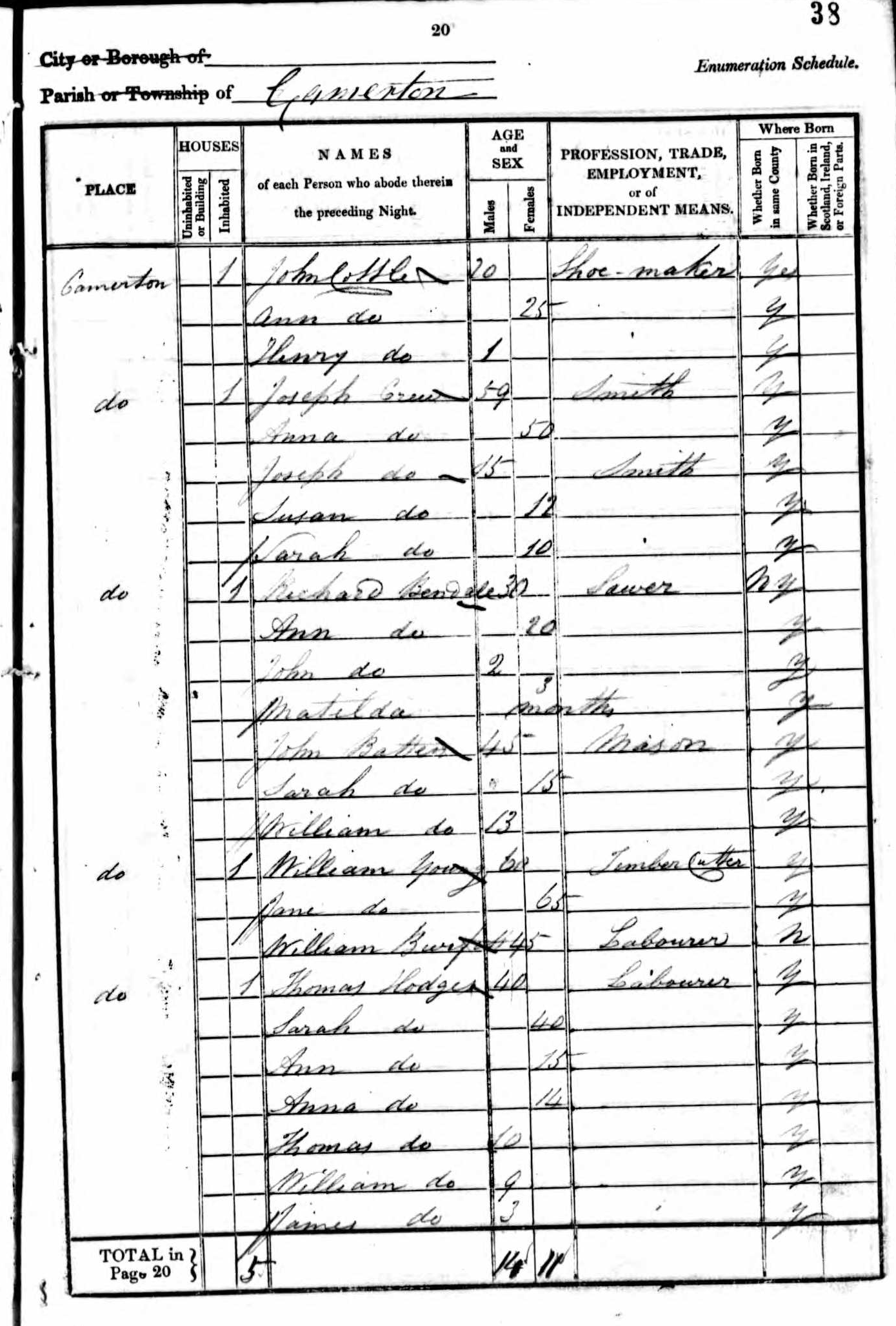

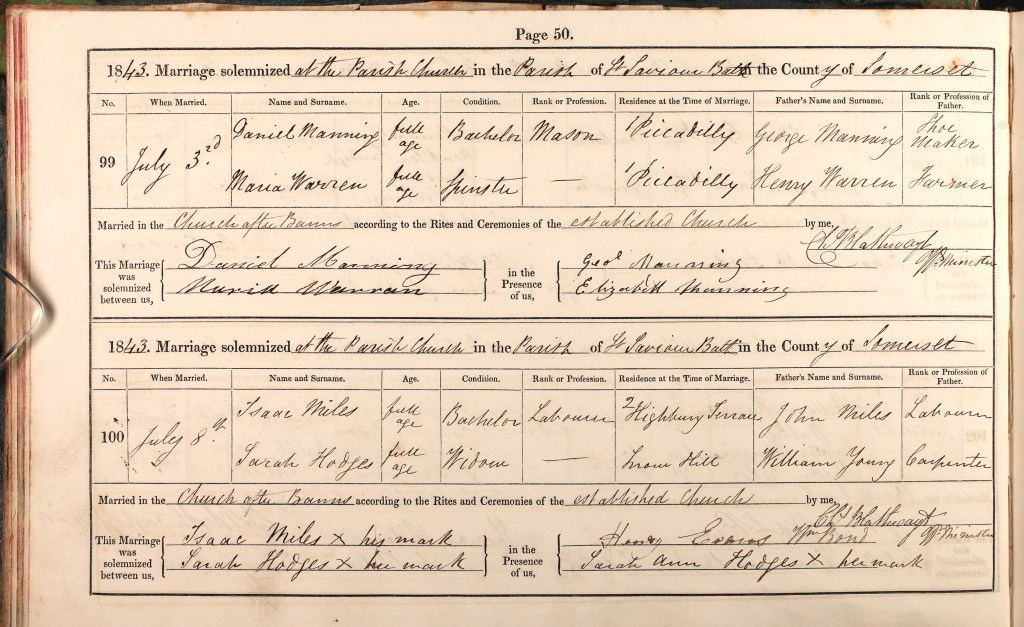

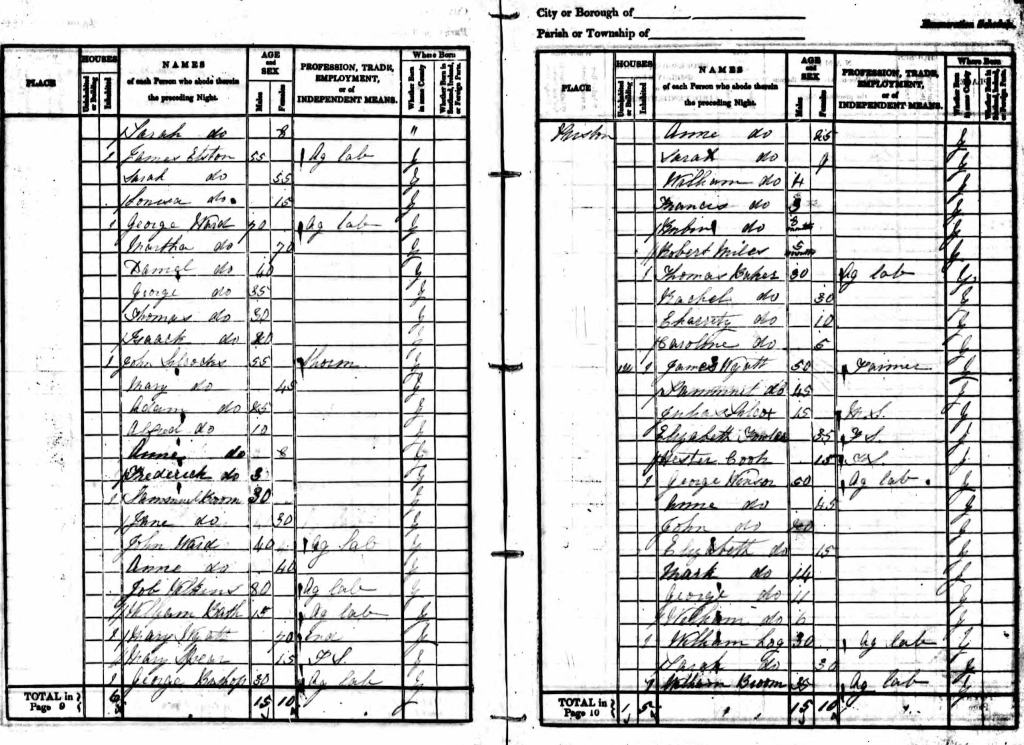

Here is the 1841 Census information for the extended John Miles Family, firstly the children of John and Elizabeth Heal:

As noted earlier, George Miles (1811- after 1851) seems to have remained single and no trace of him has been found in the 1841 census. There is a possible reference to him in the 1851 census where he is recorded as unmarried while visiting a fellow railway labourer in Sussex. No further record of George has been found.

Charles Miles (1813-1902) married Mary Weston (1816-1888) in Englishcombe in 1835 and the census of 1841 shows them living in the Englishcombe village with two sons; William 4 years old and George 5 weeks old.

Ann Miles (1815-1850) married George Bishop in Priston in 1832 and the 1841 census records them living in Priston with their children, Sarah Bishop nine-years-old, William Bishop four-years-old, Francis Bishop three-years-old, Rueben Bishop eight-months-old and a Robert Miles five-months-old. This is the first mention of Robert, tracing his birth certificate or baptism has proved an impossible task.

Who were Roberts parents and where were they for the census?

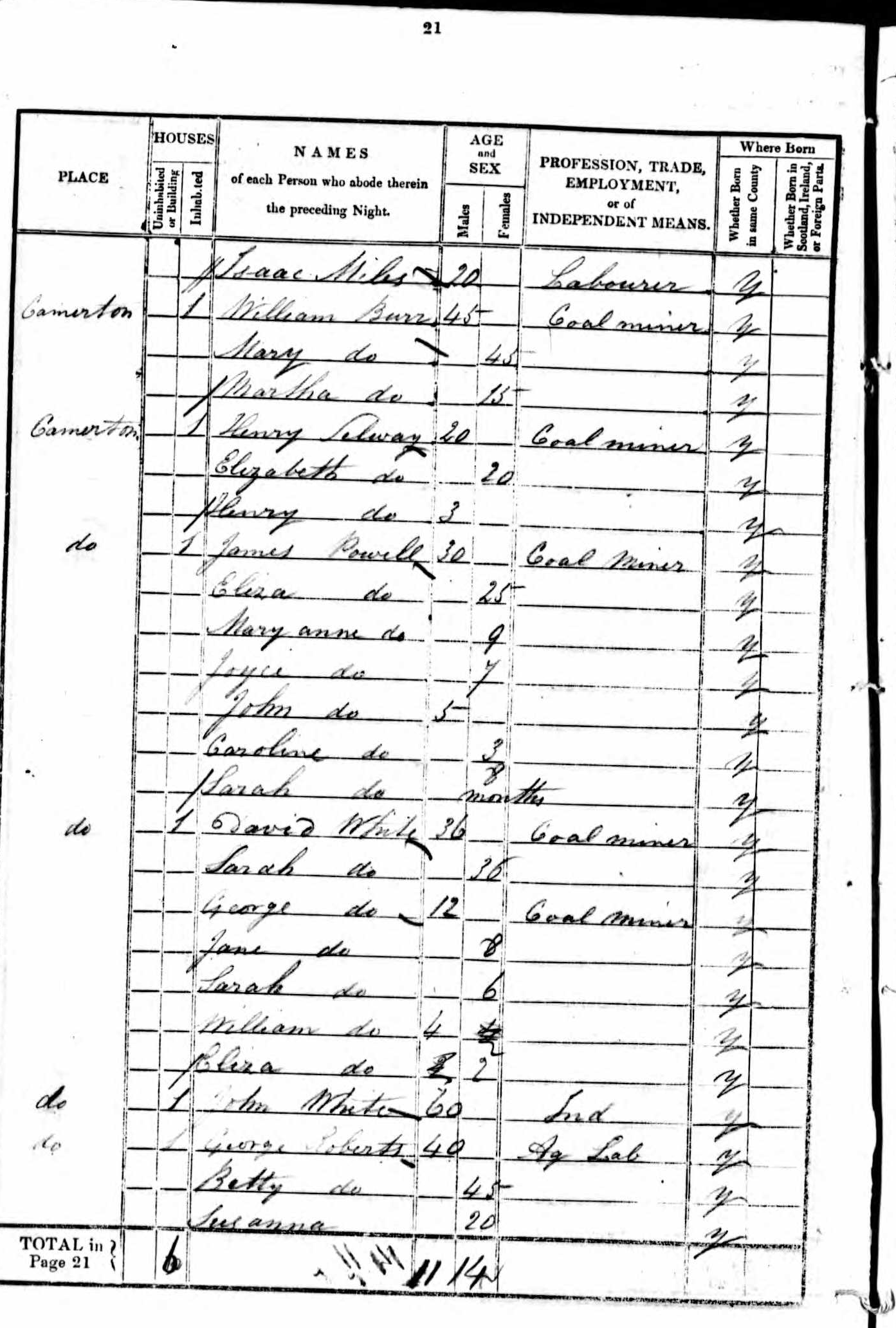

Isaac Miles (1819-1875) is recorded as a 20-year-old labourer living in Camerton with Thomas Hodges, a 40-year-old labourer and his wife, Sarah, also 40, and their five children, Ann, 15; Anna, 14; Thomas, 10; William, 9; and James 3.

On November 11th, 1841, Thomas Hodges was buried in Camerton and less than 2 years later, on 8th July 1843, his widow, Sarah Hodges married the much younger Isaac Miles at the St Saviour Parish Church on the northern outskirts of Bath, about 8 miles from Camerton. The mind boggles! The 1851 Census shows that they are no longer living together: Sarah Miles is living with her daughter, Ann and her husband Henry Lippiatt in Camerton while Isaac is a boarder in Keynsham at the house of James Cuddihy.

Elizabeth Miles (1822-1874) can’t be verified by the 1841 census – the closest record I can find that might fit is a 20-year-old Eliza Miles listed as a farm servant at Claverton, only a few miles from Priston working for/with a farmer – George Marsh and his family.

Sarah Miles (1824-1883) is not living with her father John or any other member of her Miles family. A broad search of the 1841 census throughout England for Sarah Miles brings up more than 480 possibilities, with less than 20 having Somerset listed as the place of birth. Three people recorded in Somerset may fit if we are generous with the age/birth discrepancy: a 15-year-old Sarah Miles, a servant for Thomas Barter, Surgeon in Walcot; a 15-year-old Sarah Miles, a servant at the residence of Mr. William Basnett in Bathwick and a 15-year-old Sarah Miles, a servant at Keynsham.

Closer to London there is an eighteen-year-old Sarah Miles at St Pancras, Marylebone; a sixteen-year-old Sarah Miles, servant at Brompton, Kensington; and a sixteen-year-old female servant, Sarah Miles at Lambeth, London. None of these appear to be verifiable. Sarah might not have given her details in the census or she may have already adopted the alias, Sarah Jones. I performed a similar broad census search for Sarah Jones which resulted in excess of 1,200 possibilities, but none seemed to be a good fit.

It seems that if Sarah Miles was in Somerset at the time of the 1841 census, she was either not close to her family in June 1841 or she was very close to some family and did not respond to the census. Equally, she could have already made her way to London, possibly living in a Union Workhouse or living in a situation where she did not want to be found. We have no idea of what the exact scenario was in regard to the census nor do we know if she was using the name Sarah Jones.

John Miles (1826-1903) is found at Dunkerton, recorded as a 14-year-old agricultural labourer living, probably boarding, with a Hannah Carter, 45 years old, her children James Carter, a 15-year-old coal miner and the 12-year-old Martha Carter.

Richard Miles (1828-1895) the youngest of John and Elizabeth’s children is found at Newton St. Loe, a village only 5 miles northwest of Priston. Richard is listed as a 12-year-old agricultural labourer and is living with John Cox, a coal miner, his wife Sarah and their seven children. Interestingly, in later life Richard works as a coal miner.

Here is the rest of the 1841 Census information for the extended John Miles Family, this time the children of John and Johanna Bull:

Harriett Miles (1836-aft.1911) recorded as a 4-year-old is living with her parents John and Johanna in Dunkerton. Also in the same household are Emma (1838-) a 3-year-old, Thomas (1840-1913) a 1-year-old and the 60-year-old Ann Bull, Johanna’s mother. I think that Emma was the girl born as Frances – there is a record of Frances being born to John and Johanna in 1838 but no further mention of her is found. The other six children of John and Johanna were all born at later dates.

WHO WAS ROBERT MILES?

When outlining the 1841 census information, a five-month-old Robert Miles is recorded living with George and Ann (Miles) Bishop and their family in Priston. Could this be a son born to Sarah Miles? Sarah’s possible mother figure when she was growing up was her older sister, Ann, who married George Bishop in 1832. The 1841 census shows Ann’s fourth child, a son Reuben was born in November 1840. If Robert Miles was Sarah’s son, the two sisters would have been pregnant at the same time with Sarah possibly living with Ann and her family. Ann could have nursed and cared for Robert as a newborn if Sarah wasn’t able to. Robert may have been brought up in the Bishop’s household if Sarah had left Priston for London.

Ann (Miles) Bishop top right; and 5 month old Robert Miles.

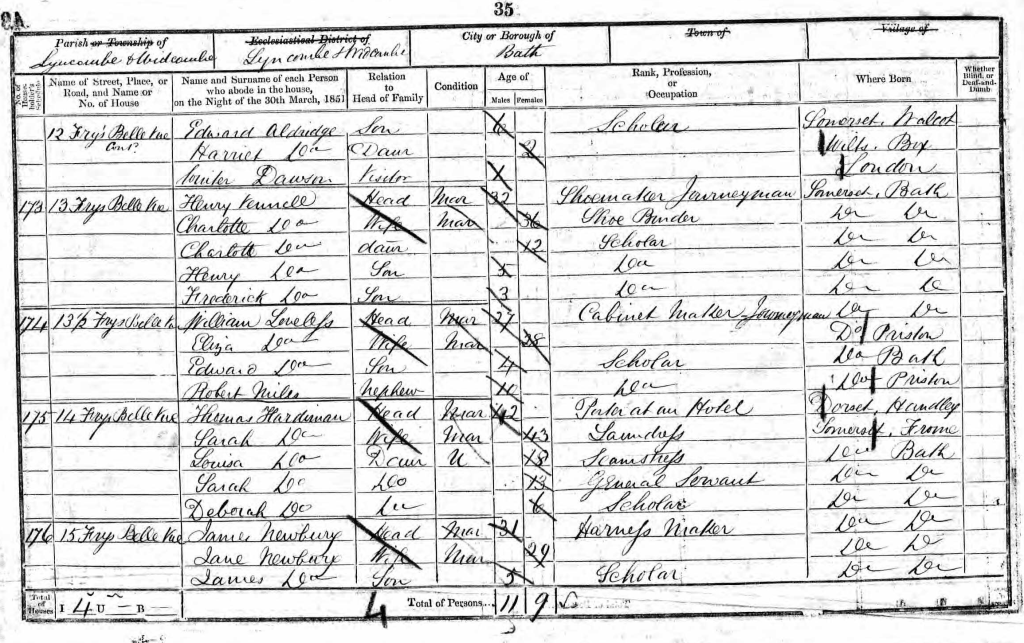

This possibility has more credence from the 1851 census. Sarah’s other sister, Elizabeth (1822-1874), had married a cabinet maker, William Loveless (1823-1874) in 1845 at the St. Philip and Jacob Church in nearby Bristol. The 1851 census records William Loveless, a cabinet maker and Eliza Loveless his wife, living at 13 ½ Frys Belle Vue in Lyncombe, Bath with their four-year-old son, Edward Loveless and a ten-year-old nephew, Robert Miles, born in Priston. Ann (Miles) Bishop, the older sister had tragically died in August 1850 and the family may have determined that Elizabeth and William were better placed to care for the ten-year-old Robert as George Bishop would have been fathering four sons. George remarried in December 1850 to an Ann Flower (1811-) and she and George may not have wanted to continue looking after a child that was not born to either of them.

their son Edward and the 10 year old nephew, Robert Miles.

If this tale of Robert’s life is correct, it could explain any anguish, pain, guilt or depression that Sarah may have experienced. It could also explain why she went to London and assumed another name.

When children were born out of wedlock, they invariably took their mother’s surname. Given the turbulent life of Sarah Miles it is not at all a stretch to postulate that she gave birth to a son, Robert in 1840 and that he was looked after by Sarah’s sisters, Ann Bishop and Eliza Loveless. Ann died in 1850 and Robert then appears with the Loveless family at the 1851 census. None of the other Miles children would have been in a position to have a child in 1840 – the sons of John and Elizabeth were either dead, married with children or too young.

I can find some pieces of what Robert Miles (1840-?) life may have been with a marriage, wife and children, but nothing absolutely conclusive. I am content to have Sarah Miles as the mother of Robert as the catalyst that saw her leave rural Somerset to chance her future in London, with disastrous results.

THE WORKHOUSE:

Throughout the research of the Miles family in this part of Somerset, the workhouses are often mentioned and given as the abode for many deaths. The term pauper is often used to describe some people’s condition or status at the end of their life. “Old” John Miles (1703-1791) who’s family had property and assets was listed as a pauper at his death. Another term, sojourner, was used to describe someone who was living in a specific parish but wasn’t born in that parish. These terms, and the actual workhouse, were part of the social and legal framework of how people were looked after during poverty and at the end of their lives. This topic will be addressed in more detail in another essay on the Miles Family but it was part of the social framework of England in the 1840’s and deserves some explanation, particularly in relation to Sarah Miles and her experience in London.

The workhouse was an institution found in England from the 17th through the 19th century that was to provide employment for paupers and sustenance for the infirm. The Poor Law of 1601 in England assigned responsibility for the poor to the parishes, which later built workhouses to employ the impoverished. It proved difficult to employ them on a profitable basis, however, and during the 18th century workhouses tended to degenerate into mixed receptacles where every type of pauper, whether needy or criminal, young or old, infirm, healthy, or insane, was dumped. These workhouses were difficult to distinguish from houses of correction. According to prevailing social conditions, their inmates might be let out to contractors or kept idle to prevent competition on the labour market.

not achieve society’s aims.

An Amendment to the Poor Law in 1834 was designed to standardise the system of relief for the poor throughout Britain, and groups of parishes were combined into unions responsible for workhouses. Under the new law, all relief to the able-bodied in their own homes was forbidden, and all who wished to receive aid had to live in workhouses. Conditions in the workhouses were deliberately harsh and degrading in order to discourage the poor from relying on parish relief. Conditions in the workhouses improved later in the 19th century.

John Miles (1795-1862) appears to have lived with three of his young children in the Keynsham Union Workhouse from 1855 to his death in 1862. Two of these children also died while at Keynsham in 1855 and 1858. John Miles was the father to 20 children from two wives, both who died in childbirth, or as a consequence of childbirth. Of these 20 children, 5 of them – 25% – did not live beyond their 6th birthday. This was also quite “normal” during these often-brutal times.

CRIMINAL LONDON:

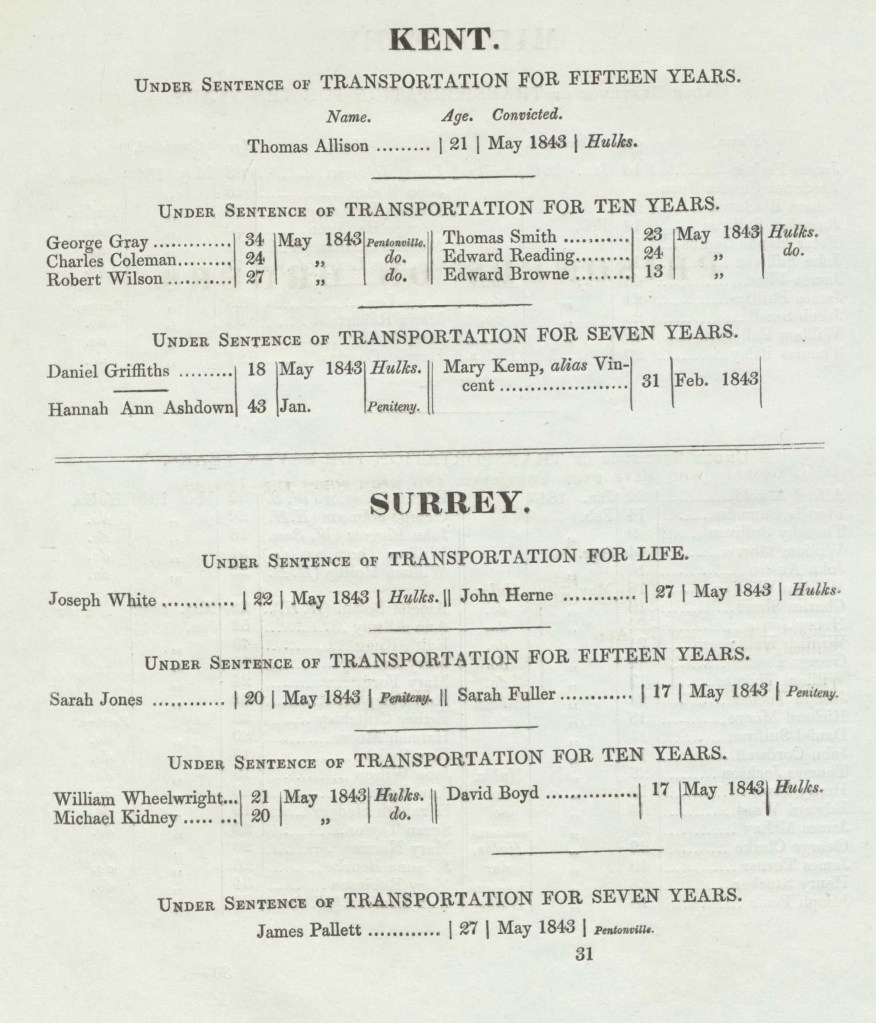

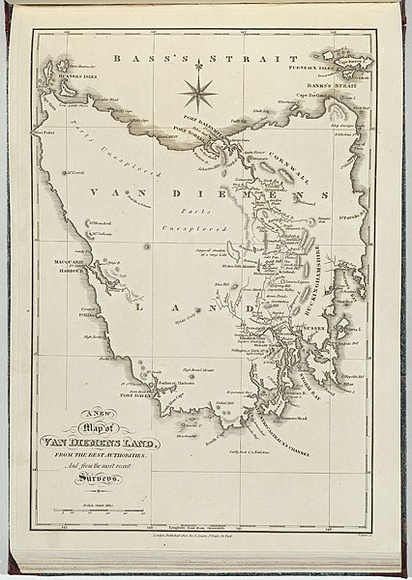

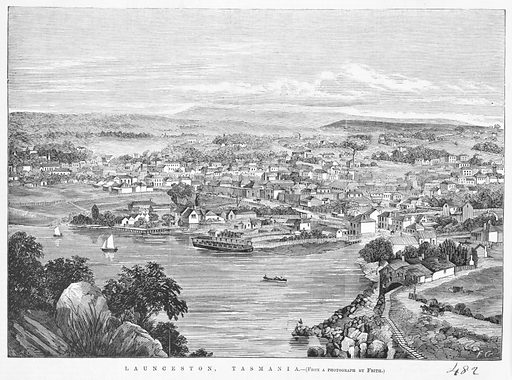

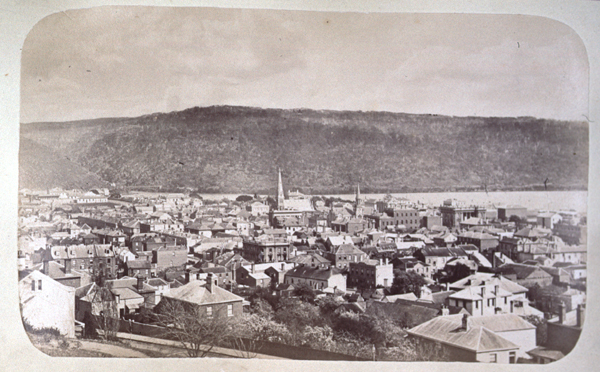

We can never know with any certainty how and why Sarah Miles (1824-1833) left rural Somerset for London. We do know that it did not end well, that she and three accomplices, Sarah Fuller (1826-1911) Joseph White & Thomas Allison were convicted for stealing clothes in Southwark. Joseph White was sentenced to transportation for life, Thomas Allison and the two Sarahs were each sentenced to 15 years transportation to Van Diemen’s Land, modern day Tasmania. Both Sarahs survived horrific conditions in gaol, transportation and living as convicts in a penal colony. They both married, they both had children, they both lived in Launceston but did not leave Tasmania.

Sarah Miles would have been able to get to London on a train leaving from Bristol that would have stopped at a number of places, Bath being one. The journey was made inexpensive in 1840 by allowing a 3rd class ticket on freight trains; we have no way of verifying that this is how (and when) Sarah travelled to London, but it is very possible. Her older brother, George Miles was working as a railway labourer for some of his life and may have provided information to his younger sister that gave encouragement to pursue an alternative to her life in rural Somerset.

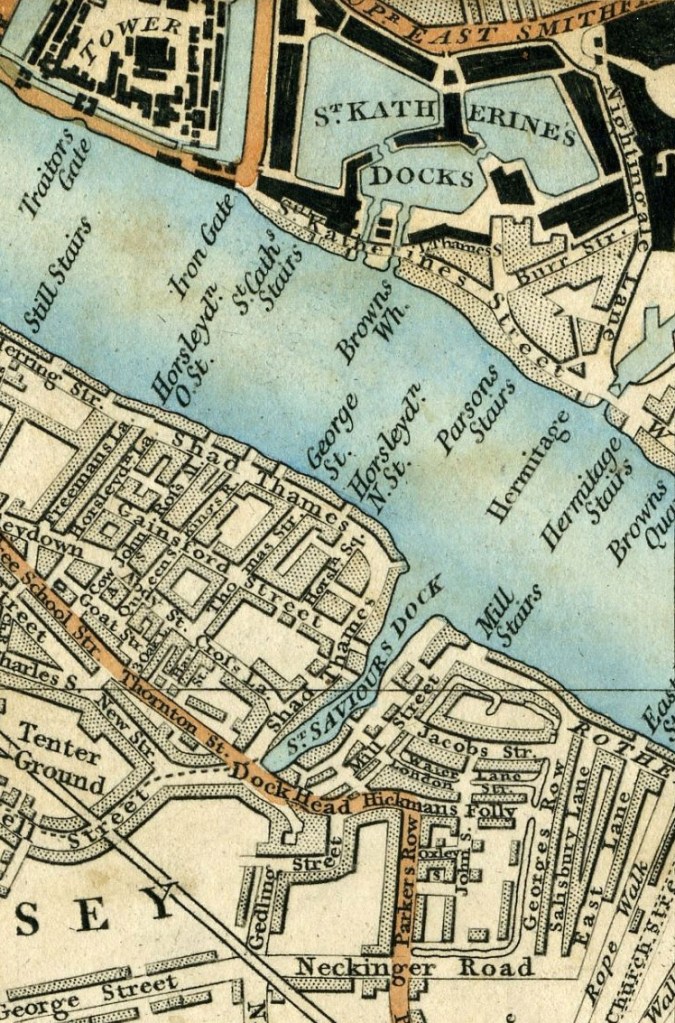

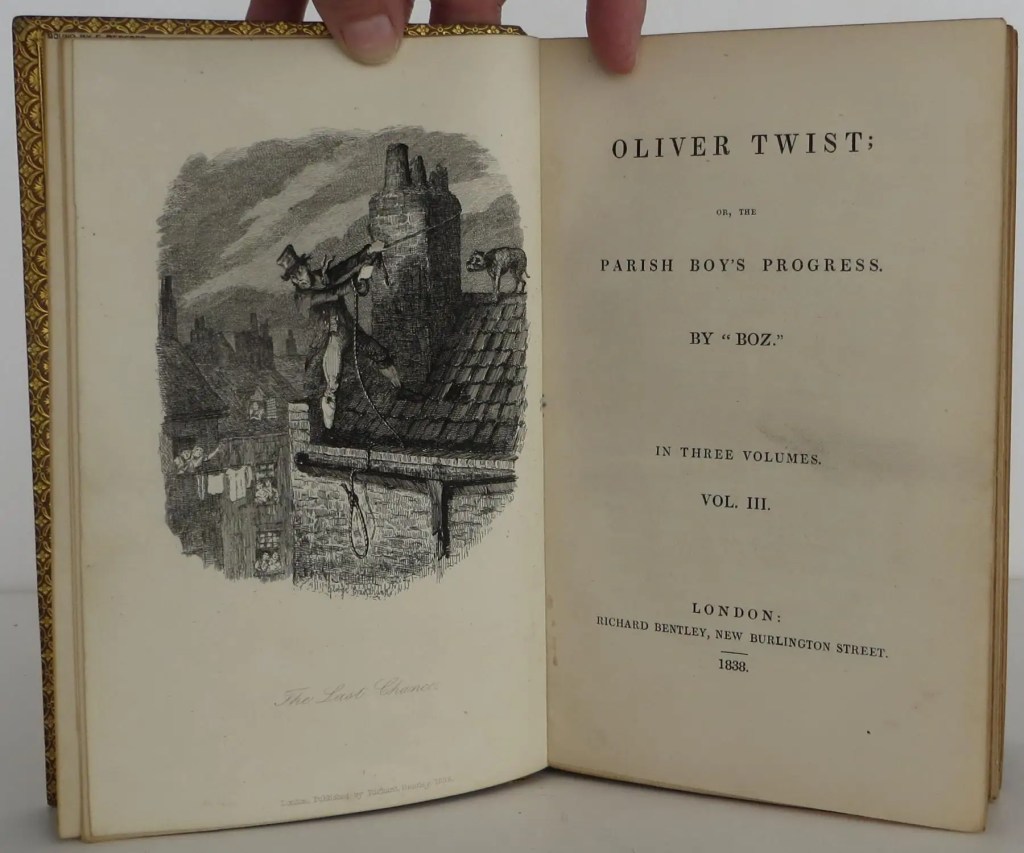

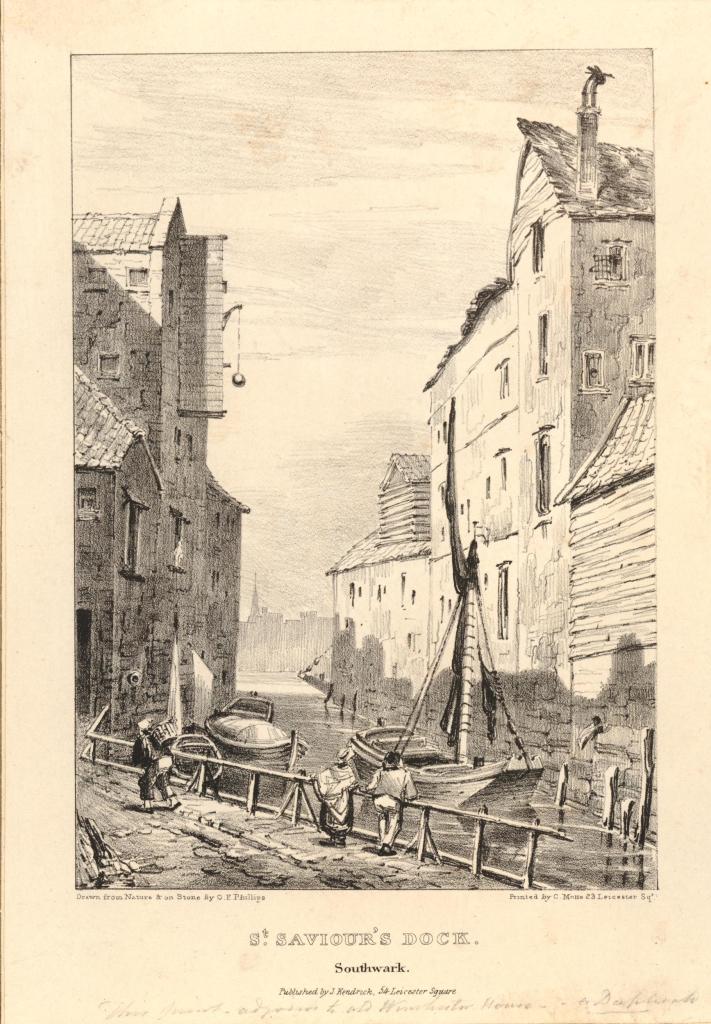

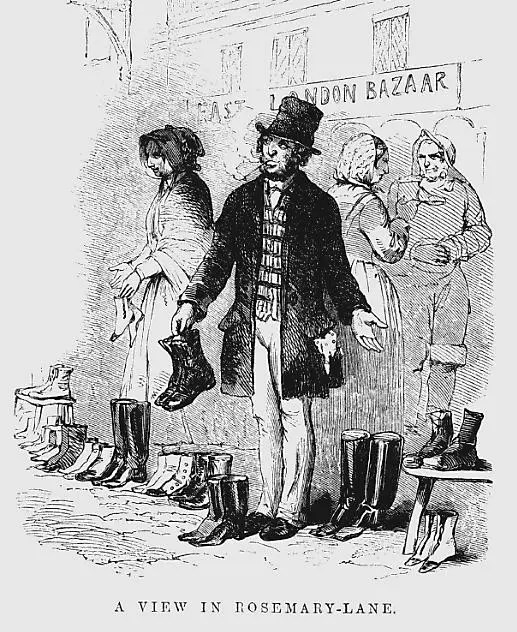

Sarah Miles and Sarah Fuller were apprehended on Thornton Street, Southwark, a part of London illuminated by Charles Dickens in his books of social commentary, particularly “Oliver Twist”. London’s population more than doubled from less than one million in 1801 to almost two million by 1841. Although improved mortality rates was a factor of the overall population growth in the 19th century, the rise in population was mainly due to migration. London was the largest, most vibrant city in the world during the 19th century. At mid-century almost 40% of Londoners were migrants from elsewhere – from provincial Britain and Ireland, Europe and increasingly from the wider world. This ensured that London’s population was remarkably young and single – influenced by the large number of people drawn to the capital seeking employment.

When Sarah Miles arrived in London there was an existing crisis surrounding relief for the poor. We touched on the workhouses earlier in this account and although the amendments to the Poor Law of 1834 were well intentioned, in the rapidly growing London the results were so appalling Charles Dickens was driven to write his stories in an attempt to reform conditions. Those unable to work were required to live in the workhouses where families and spouses were separated and subject to prison-like conditions, and where those deemed able to work were denied any assistance at all. Reports of atrocious conditions, corruption and inept management persisted throughout the century. Dickens was one of the law’s outspoken critics, using literary characters like Oliver Twist to humanise the problem and expand awareness.

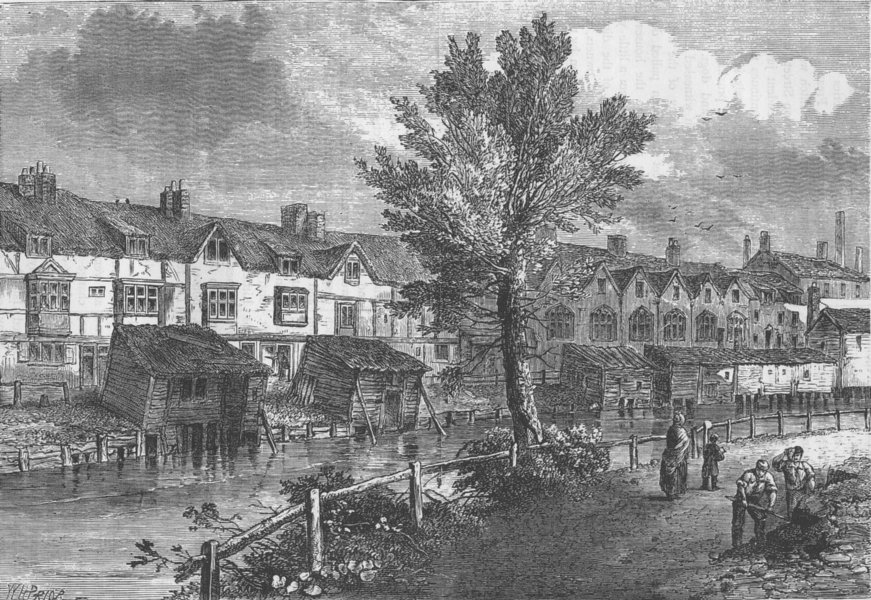

In “Oliver Twist” Dickens describes the place, Jacob’s Island, which was Bill Sikes’ last refuge. Jacobs Island was less than half a mile from where Sarah Miles and her associates were apprehended for stealing.

“Near to that part of the Thames on which the church at Rotherhithe abuts, where the buildings on the banks are dirtiest and the vessels on the river blackest with the dust of colliers and the smoke of close-built low-roofed houses, there exists the filthiest, the strangest, the most extraordinary of the many localities that are hidden in London, wholly unknown, even by name, to the great mass of its inhabitants.

‘Beyond Dockhead, in the Borough of Southwark, stands Jacob’s Island, surrounded by a muddy ditch, six or eight feet deep and fifteen or twenty wide when the tide is in, once called Mill Pond, but known in the days of this story as Folly Ditch. It is a creek or inlet from the Thames and can always be filled at high water by opening the sluices at the Lead Mills from which it took its old name. At such times, a stranger, looking from one of the wooden bridges thrown across it at Mill Lane, will see the inhabitants of the houses on either side lowering from their back doors and windows, buckets, pails, domestic utensils of all kinds, in which to haul the water up; and when his eye is turned from these operations to the houses themselves, his utmost astonishment will be excited by the scene before him. Crazy wooden galleries common to the backs of half a dozen houses, with holes from which to look upon the slime beneath; windows, broken and patched, with poles thrust out, on which to dry the linen that is never there; rooms so small, so filthy, so confined, that the air would seem too tainted even for the dirt and squalor which they shelter; wooden chambers thrusting themselves out above the mud, and threatening to fall into it, as some have done; dirt-besmeared walls and decaying foundations; every repulsive lineament of poverty, every loathsome indication of filth, rot, and garbage; all these ornament the banks of Folly Ditch.

‘In Jacob’s Island, the warehouses are roofless and empty; the walls are crumbling down; the windows are windows no more; the doors are falling into the streets; the chimneys are blackened, but they yield no smoke. Thirty or forty years ago, before losses and chancery suits came upon it, it was a thriving place; but now it is a desolate island indeed. The houses have no owners; they are broken open, and entered upon by those who have the courage; and there they live, and there they die. They must have powerful motives for a secret residence, or be reduced to a destitute condition indeed, who seek a refuge in Jacob’s Island.”

History has always demonstrated that in times of rapid growth in population, commerce or both that many sins are covered up and that the greater majority of the young, naïve and powerless are quickly chewed up, swallowed and spat out.

Such was the fate of Sarah Miles.

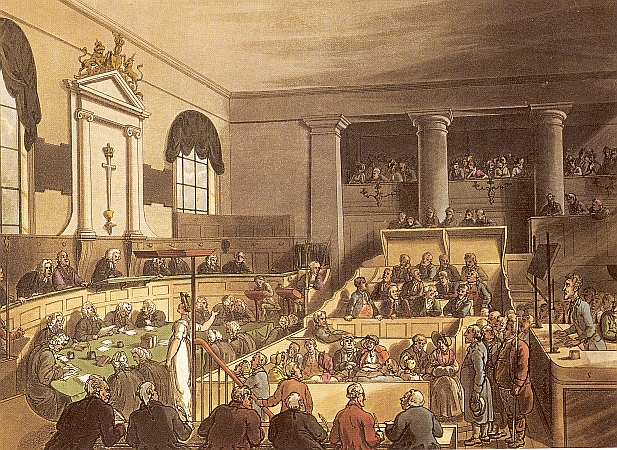

THE LEGAL SYSTEM:

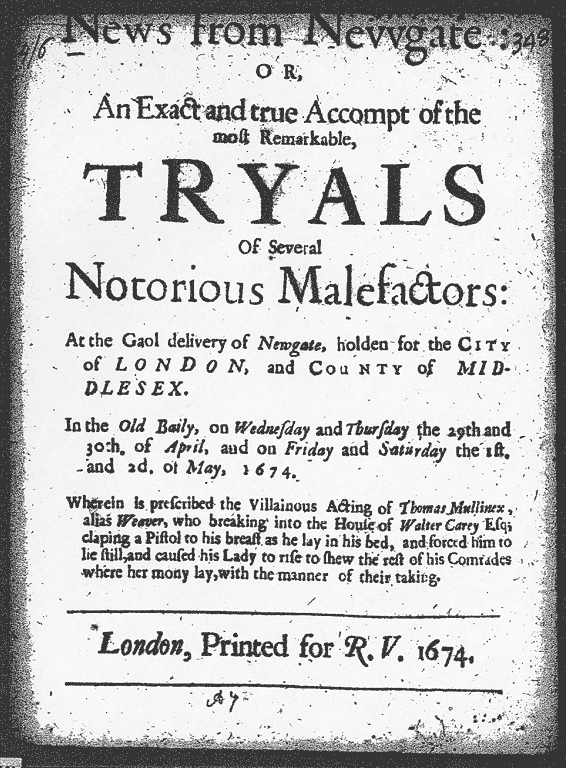

We are able to track the apprehension, trial and sentencing of many London crimes from the late 1600’s through to 1913 through a website called “London Lives”. The site gives some explanation to the history and process of publishing trials at the Old Bailey. https://www.londonlives.org

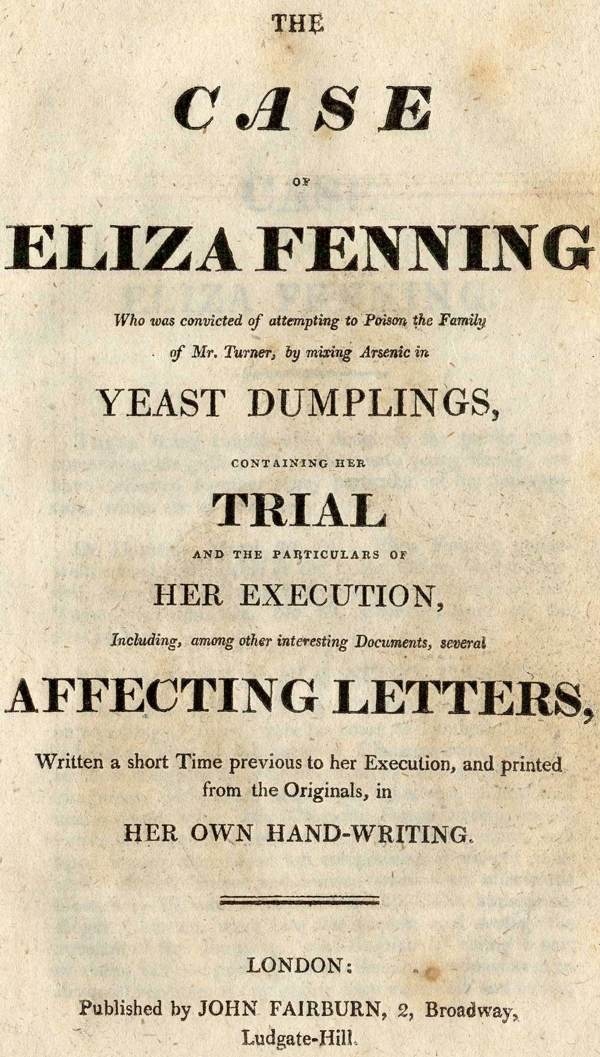

In the 1670s, in London, perhaps as a result of growing concern about crime, there was an explosion of crime literature targeted at a popular audience, including criminal biographies, of the lives of condemned criminals, last dying speeches, and trial accounts.

These early Proceedings were similar to earlier chapbooks with their sensationalist and judgemental approach, and they were very selective in the trials they chose to publish.

Early editions of the Proceedings were between four and nine pages long, included brief summaries of trials, and were not necessarily comprehensive. Nonetheless, by the mid-1680s most trials seem to have been reported. Around 1712 the Proceedings began to include some verbatim testimony, especially in trials which were thought to be salacious, amusing, or otherwise entertaining. By this point the Proceedings was an established periodical, read enthusiastically by Londoners seeking news, moral instruction, or entertainment. To make the Proceedings more attractive to readers in the face of competition from daily newspapers and published compilations of trials, they were expanded to twenty-four pages, and included yearly indexes, cross-referencing between trials, advertisements at the back, and, most importantly, much greater use of verbatim accounts of the testimony of prosecutors, witnesses and defendants, as well as judges’ comments and questions (this was facilitated by the use of shorthand note-takers). Ordinary trials were still treated very briefly, in order to allow more space for accounts of the more exciting trials, including murders, sexual crimes, and thefts from the person (which usually involved prostitutes).

By the late eighteenth century, public interest in the lives of ordinary criminals was waning. The Proceedings came to provide much less sexually explicit testimony and the number of trials reported increased significantly. At the same time, accounts of what happened at the Old Bailey were reported in increasing detail in the newspapers.

In 1775, the City of London began to take a greater interest in controlling the content of the Proceedings, and in 1778 it demanded that the Proceedings should provide a “true, fair, and perfect narrative” of all the trials. In part, this requirement resulted from the fact the Proceedings were being used by the Recorder (the principal legal officer in the City) as a formal record: they formed the basis of the Recorder’s report to the King concerning whether the convicts sentenced to death should be pardoned or executed. Moreover, at a time of social instability, the City of London was concerned to demonstrate to the public the fairness and impartiality of judicial procedures at the Old Bailey.

to most people caught up in the legal system.

They were now provided less for the purpose of entertainment than as a means of keeping an accurate public record of events which transpired in the courtroom. Their commercial viability was increasingly undermined by their length and detail, and in the 1780s publishers began to target the Proceedings at a legal audience, taking advantage of the increasing number of lawyers present at the Old Bailey.

Despite their limited audience, the Proceedings continued publication until 1913. The Proceedings are “probably the best accounts we shall ever have of what transpired in ordinary English criminal courts before the later eighteenth century”. Although initially aimed at a popular rather than a legal audience, the material reported was neither invented nor significantly distorted. The Old Bailey courthouse was a public place with numerous spectators, and the reputation of the Proceedings would have quickly suffered if the accounts had been unreliable. Their authenticity was one of their strongest selling points, and a comparison of the text of the Proceedings with other manuscript and published accounts of the same trials confirms that what they did report was for the most part reported accurately. At the same time, the Proceedings are far from comprehensive transcripts of what was said in court.

Many types of information were regularly omitted, notably details of defence testimonies, legal arguments, and the judge’s summing up. For this reason, one should not argue from silence – one should not conclude that because something was not reported in the Proceedings, it was not said or did not occur in court.

The case for the defence was most affected by these omissions. In comparison to the case for the prosecution, testimony by the defendant, his or her counsel, and defence witnesses was more likely to be abridged or entirely omitted, especially when the defendant was acquitted. This had the cumulative effect of making those tried at the Old Bailey seem more culpable in the Proceedings than they appeared in court and can make it difficult to understand why so many defendants were acquitted.

What I take from all of this is that a lot of actual court records, particularly the defence, was not recorded nor been preserved. Which for me, shows that people like Sarah tended to get a raw deal as their illiteracy and the political need for “slave labour” in England’s colonial empire ensured that the poor would always provide a ready source of human capital being churned out of the legal system. Some would argue that not much has changed over the last 200 years!

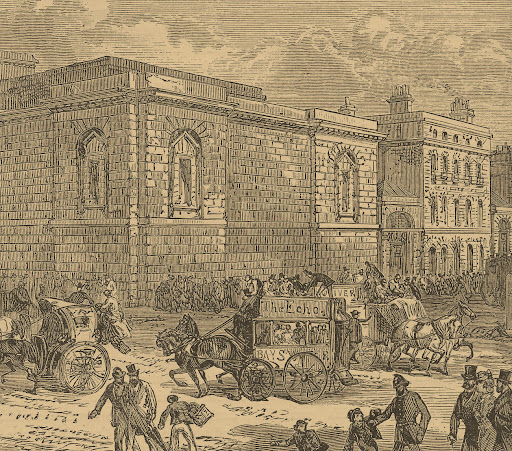

THE GAOLS:

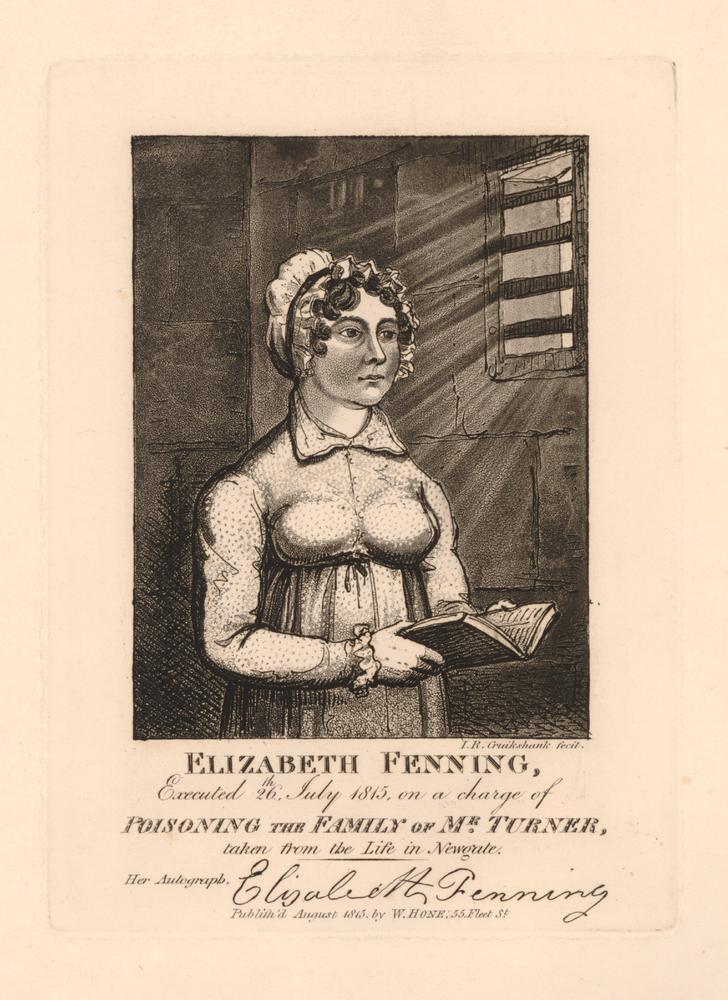

Sarah Miles, her friend Sarah Fuller and two young men, Thomas White and Thomas Allison were apprehended on the 10th of April 1843 and taken across the Thames to Newgate Prison for processing and scheduling of their trial.

Newgate was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the old Roman Wall, built at the site of Newgate an actual gate in the wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, Newgate Prison was extended and rebuilt many times, and remained in use for over 700 years, from 1188 to 1902.

In the late 18th century, executions by hanging were moved to Newgate Prison from the Tyburn gallows. These displays of public sport took place on the public street in front of the prison, drawing crowds until 1868, when they were moved into the prison.

were great public entertainment.

For much of its history, a succession of criminal courtrooms were attached to the prison, commonly referred to as the “Old Bailey”. The present “Old Bailey”, now officially Central Criminal Court, now occupies much of the site of the prison.

On the 26th April 1843, after spending two weeks at Newgate Prison, Sarah and her co-accused were committed for trial at the Old Bailey by a Police Magistrate, John Cottingham Esquire.

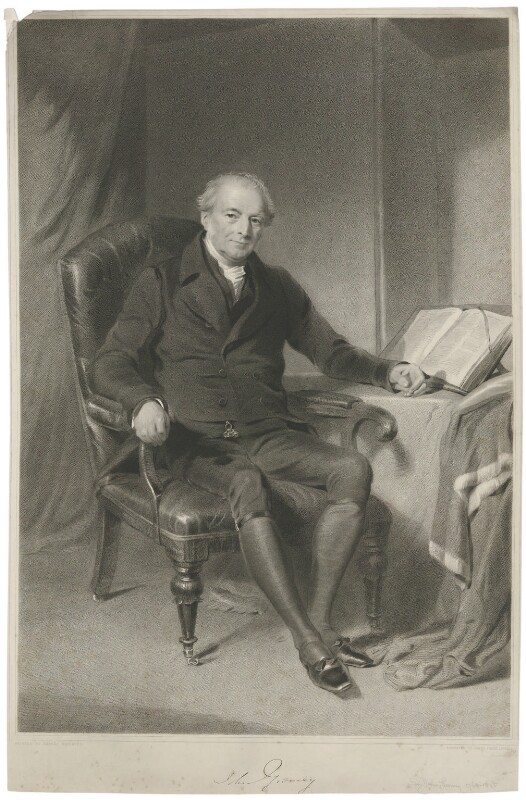

On the 8th of May 1843, after four weeks of horrific conditions in Newgate Prison with very little food or water, washing facilities or clean clothes to wear, Sarah and her co-defendants were taken to the Old Bailey to have their case presented to Judge Baron Gurney, who at 75-years-old was rapidly approaching the end of his career.

This judge was not a radical legal reformer who had a view anywhere remotely similar to Charles Dickens. Gurney was born in London on 14th February 1768 into a noted family of stenographers. Trained in the law, John Gurney was called to the Bar in 1793. He was made King’s Counsel in 1816. In November 1835, he achieved notoriety becoming the last judge in England to sentence a capital punishment for sodomy. Gurney convicted James Pratt and John Smith under section 15 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1828 (which had replaced the Buggery Act 1533). In 1832 he was appointed a baron of the exchequer and knighted. Gurney was noted as an independent, albeit harsh judge, and held the position for over a decade until he was forced to resign in January 1845 due to ill health, dying two months later on 1 March 1845.

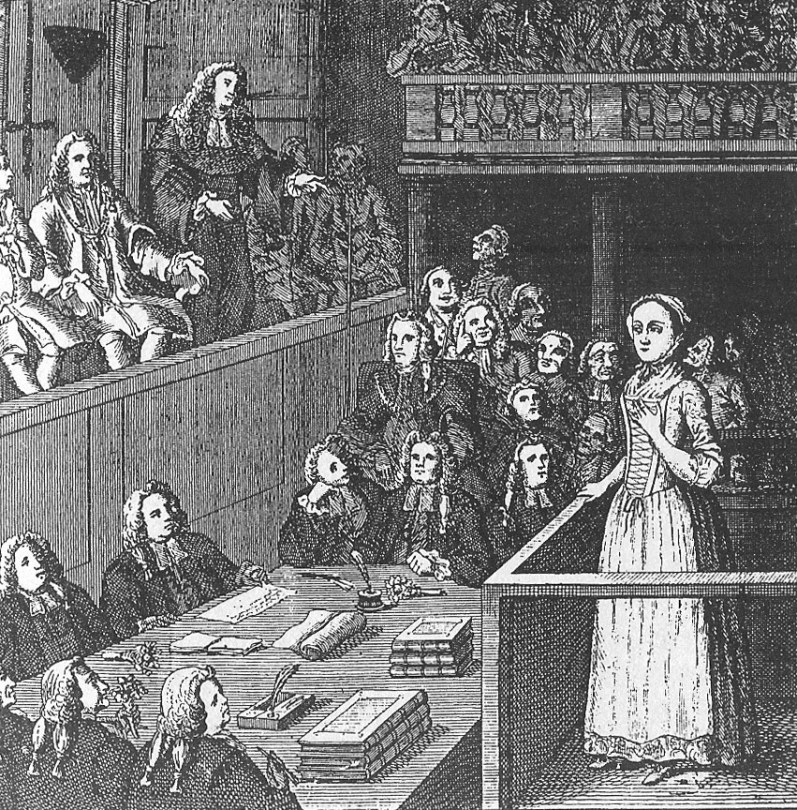

THE TRIAL :

As faithfully recorded:

CASE NUMBER 1694.

THOMAS WHITE, THOMAS ALLISON, SARAH JONES , and SARAH FULLER , were indicted for burglariously breaking and entering the dwelling-house of Elizabeth Hackett, about twelve in the night of the 9th of April, at St. John, Southwark, with intent to steal, and stealing therein, 24 shirts, value 2l. 8s., and 10 pairs of trowsers, 7l., her property; and that White had been before convicted of felony.

ELIZABETH HACKETT. I am single and keep a slop-shop in Thornton-street, Dockhead, in the parish of St. John. On Sunday night, the 9th of April, I went to bed at eleven o’clock—the house was all safe—just before twelve I heard a great noise, got up, opened the window, but could see nobody but a woman at the top of the alley—I went down about seven in the morning, found the fan-light over the door broken right in, sufficiently for a person to get into the house—a bundle of shirts was taken away, and ten pairs of trowsers, worth 9l. 12s. 6d.

GEORGE GALE . I sell coffee and ginger-beer, and live in Brewer’s-court, Horsleydown, in the next street to the prosecutrix—I saw the four prisoners that night, a little after four o’clock, with another not in custody, in Thornton-street,—they passed by me—they had nothing with them that I saw—I asked them if they wanted any coffee or ginger-beer—White made some remark and they went on about twenty yards, then stopped for about five minutes, and seemed to be considering—they came back—I had a cane on my truck—White took it up—I told him to put it down, it was not his property—we had a tustle to get it—then Allison came back to him, and said something—I thought I heard they should be blown or something, and he gave me the cane, they all five went on, and turned into New-street, which is at the back of Thornton-street—in ten minutes or a quarter of an hour I saw them come into an alley—White came forward, and seemed to be talking to somebody behind—they stood there some time, went back, and appeared to go into New-street, into Thornton-street—the female prisoners went and stood by the post-office, about 100 yards from the prosecutrix’s—the male prisoners came up the street—Allison went down a court by the side of the house, and then White went down—I went towards the place, to see what they were doing—the male prisoners crossed the road, and went down towards the females, and the man not in custody walked down on the same side of the way as the prosecutrix’s shop—that was the last I saw of them till I saw the women in custody that evening, and White and Allison on the Saturday following.

Allison. I was not before the Magistrate.

Witness. No, he was not—I never knew any of them before.

THOMAS TURVEY . I am a policeman. On Monday morning, the 10th of April, about nine o’clock, I was going on duty on Southwark-bridge-road—I saw all the prisoners and one not in custody in company—the two females had something in both their aprons—I asked them what they had—they said, “Some work”—I asked where they got it from—Fuller said her sister was in the habit of taking out work from a slop-shop, and they were going to take it home to their sister—I asked what they had to do to them, or if they were finished—they could not tell me—I asked them to let me look at them, which I did, and asked where their sister lived—they said a little way along the street, that is Norfolk-street—I said I would go with them—the men went on, and when they found I detained the women they all three ran away—I took the women to the station—in a few minutes after the prosecutrix came to give information of her shop being broken open and property stolen—she claimed the property—I had seen the three men frequently before—I am sure White and Allison are two of them.

White. I was forty yards from the females when you stopped them.

Witness. He was not further than I am from him now—they were all five together—I had followed them nearly 150 yards—they were talking till they saw me close on them, and then the men made away from the women.

MRS. HACKETT re-examined. This is part of the property I lost—I know the shirts by the make, as well as by a particular mark in the cotton, which I noticed when I had them.

White’s Defence. I met the two females on the other side of London-bridge; they asked me to give them something to drink; I said yes, if they came to the house I would. We went and had three or four pots of beer together; they asked me to give them a breakfast, which I did, at eight o’clock. I then said, “I must go to my work.” I had got a little way along Southwark-bridge-road, and saw them coming after me. I afterwards looked behind, and saw them with the policemen I met two strange men in the street; this was not one.

Jones’s Defence. On Sunday night a young woman who I knew asked me to mind the shirts for her; she must pawn them on Monday morning; she said she was taking them to her sister’s; the policeman has told a great story.

Allison’s Defence. I can prove where I was at the time the robbery was committed, but have not had time. I had nothing to do with the robbery.

WILLIAM KEATING . I am a policeman. I produce a certificate of White’s former conviction, from the office of the Clerk of the Peace for Surrey—(read)—I was present at the trial—he is the man—he was tried by the name of John Smith.

WHITE— GUILTY . * Aged 22. Transported for Life.

ALLISON— GUILTY . *Aged 23. Transported for Fifteen Years.

JONES— GUILTY . Aged 20. Transported for Fifteen Years.

FULLER— GUILTY . Aged 17. Transported for Fifteen Years.

top left is The Old Bailey and Newgate Prison.

Appearing in the Old Bailey, or any court would have been an extremely intimidating process, especially if it were the first instance. As we have noted there was no opportunity to wash, shave or change into clean clothes. The dignitaries, prosecutors, police, bailiffs, lawyers and clerks were all very comfortable with their roles and would not have extended any sympathy or empathy to those poor unfortunates who innately knew that they were not going to receive anything but a hostile reception from any of the players in this game of life, death and imprisonment. Very few death sentences were delivered as not only were reforms to crime and punishment being made during the 19th century, but in the 1830’s and 1840’s this “sausage machine” needed warm, breathing bodies to be used as free labour in the antipodean colonies. Between 1787 and 1868, a total of 164,000 convicts were landed in New South Wales, Van Diemen’s Land and Western Australia. The pattern of punishment sentences at the Old Bailey changed dramatically over time. Between 1674 and 1717 the most common sentences were death and branding, together with a significant minority of corporal punishments. Following the Transportation Act, between 1718 and 1775 transportation to North America became the dominant sentence, with a declining but still significant proportion of convicts sentenced to death. After the interruption caused by the American War, between 1787 and the 1840s transportation to Australia and imprisonment in Britain were dominant, while death sentences and corporal punishments declined. Finally, in the second half of the nineteenth century imprisonment was overwhelmingly the most common sentence.

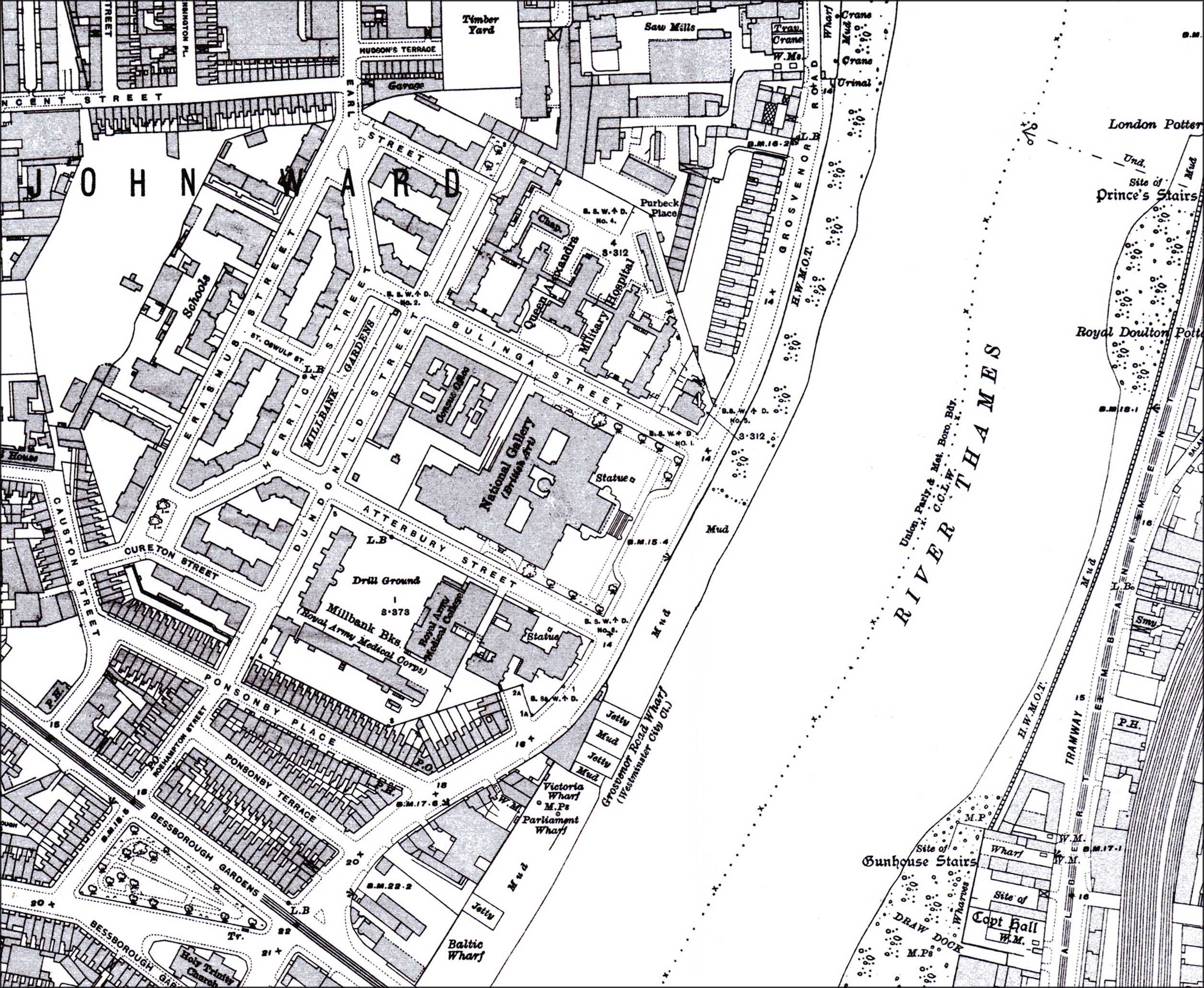

The two Sarahs could be considered very unlucky to have committed and been apprehended for their crime of stealing at the time they did – 1843. Females were in short supply in the colonies, so young women were invariably sentenced to transportation. They had been found guilty (no appeals tolerated), sentenced and on the 11th May 1843 were taken across the Thames, just past Westminster, to Millbank Prison.

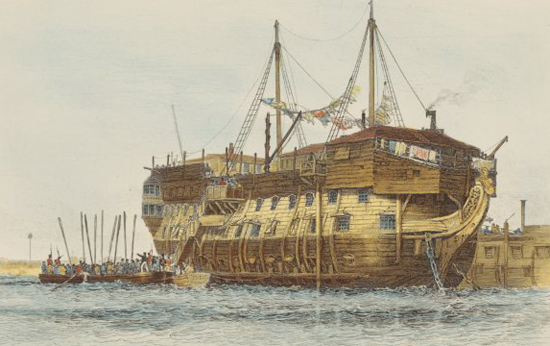

This is a condensed description of this important piece of infrastructure that was designed, in part to replace the disease-ridden hulks that were the link, the “holding pens” between sentence and transportation.

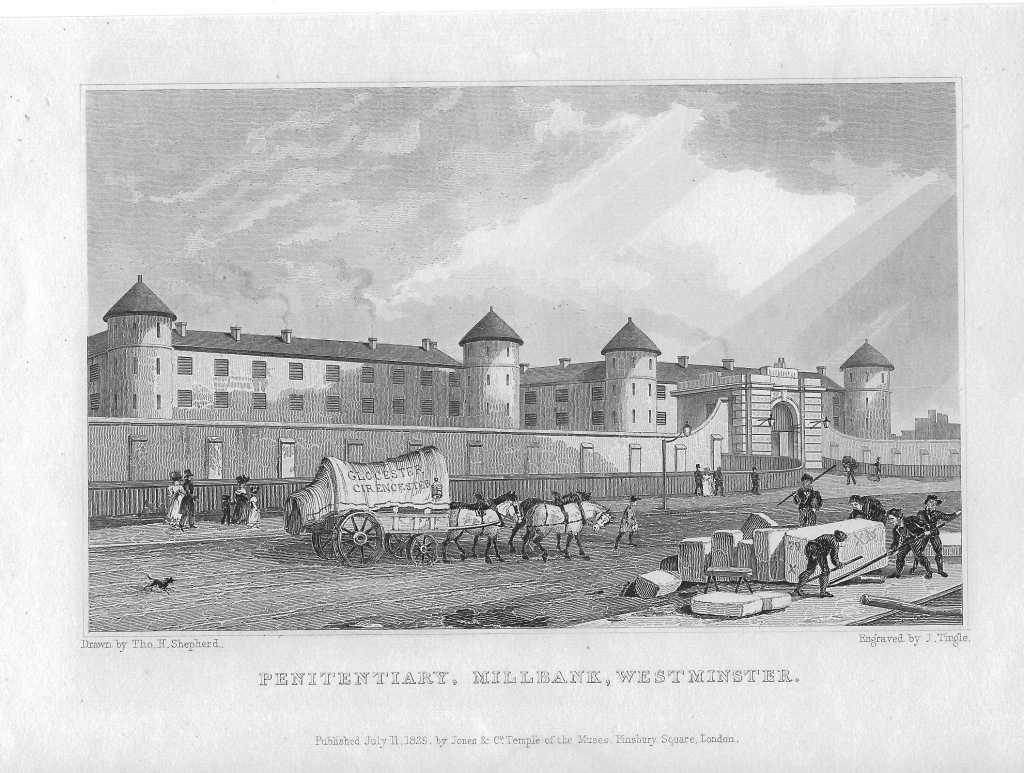

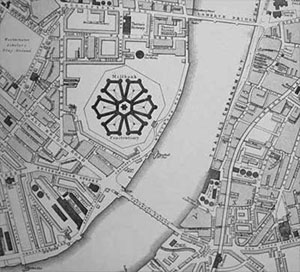

“Millbank takes its name from the mill that belonged to Westminster Abbey and stood on the isolated marshy foreshore that linked Westminster to Chelsea. The mill was demolished around 1736 by Sir Robert Grosvenor, who built a house that stood on the site until 1809, when the land was set aside to build London’s largest prison.

Millbank Penitentiary was completed in 1821 and cost £500,000 to build, an immense sum at the time. Initially it was hailed as the greatest prison in Europe because of its pioneering ‘panopticon’ design. This had been devised by Jeremy Bentham, the philosopher and philanthropist. At its centre was the Governor’s House, which allowed prison guards to keep watch over 1,500 transportation prisoners housed in separate cells in the surrounding pentagonal blocks. There were three miles of cold, gloomy passages: the turnkeys invented a code of chalked directions to stop getting lost in the maze!

From above, it was like a vast six-petalled flower of dirty yellow brick, a multi-turreted fortress with bars at the windows. Surrounding it was a stagnant outer moat, enclosing over 16 acres of cold, damp squalor. It provided the perfect conditions for cholera to flourish. It was soon notorious enough for Dickens to include it within his novel David Copperfield. He described the area as ‘a melancholy waste … A sluggish ditch deposited its mud at the prison walls. Coarse grass and rank weeds straggled over all the marshy land.’

Up to 1868, everyone sentenced to transportation was processed through Millbank to determine their ultimate grim destiny: around 4,000 people each year were transported to the far side of the world. Millbank had been intended to replace the notoriously unhealthy ‘hulks’ as a staging post for convicts sentenced to transportation. However, Millbank Prison was to do nothing to improve the health of those awaiting exile. Indeed, the design and location of the prison was to ensure that it was to be devastated by the cholera pandemic of 1849.”

Although large-scale transportation ended in 1853 for a number of reasons, humanity included, it continued on a reduced scale until 1867. Millbank then became an ordinary local prison, and from 1870 it was used as a military prison. By 1886 it had ceased to hold inmates, and it closed in 1890. The land was deemed to be suitable for the construction of an art gallery to house a fine collection owned by Sir Henry Tate. Demolition of the old prison began in 1892, and the gallery opened on 21 July 1897 as the National Gallery of British Art. However, from the start it was commonly known as the Tate Gallery, after its founder and in 1932 it officially adopted that name.

Two months after sentencing, at the end of July 1843 the two Sarah’s were moved from Millbank Prison to the Woodbridge, the ship that would transport them to the other side of the world. About a month later, on the 3rdof September 1843 the Woodbridge sailed from Woolwich for Hobart, Van Diemen’s Land.

Thomas White sentenced for life, was transported to Sydney on the Maitland, which departed on the 26thAugust 1843.

Thomas Allison, with a 15 year sentence was transported to Van Diemen’s Land from Plymouth on board the Anson on the 23rd September.

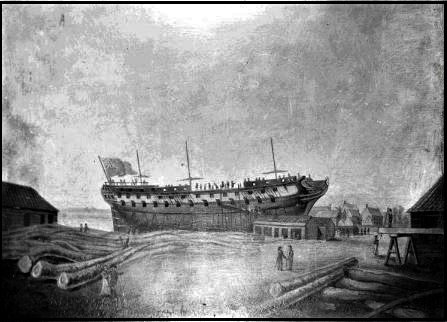

“Anson” and “Maitland” were two older ships used to transport convicts to Van Dieman’s Land.

THE VOYAGE OF THE WOODBRIDGE:

The Woodbridge was a 516-ton sailing ship originally named the Beemolah that had a very chequered and varied history. With a length of 35.1m and a breadth of 9.8m, it was built by Matthew Smith of Howrah, Calcutta and launched on the 21st of November 1808. It was based in India and was used for trade in the region and with China. She made two voyages to England for the British East India Company, one before her name changed to Woodbridge in 1812, and one after. She spent most of her career trading with the East Indies. The US Navy captured her in 1814 but the British Royal Navy recaptured her within hours. She also made two voyages transporting convicts under the command of William B. Dobson, master. The first voyage to New South Wales (1839-1840) transported 230 male convicts to Sydney with one convict death. The second voyage was to Van Diemen’s Land arriving two days before Christmas Day 1843 with 203 female convicts and no convict deaths.

It appears that the voyage from England, down the coast of Africa, around Cape Town and across the bottom of the world to Hobart was without major weather incidents. It would have been uncomfortable, damp, miserable, with all female convicts feeling endlessly sick, nauseous and at times absolutely terrified as the ship lurched, creaked, groaned and shuddered with great force. Night inside the ship would have been particularly frightening, unable to see where and how the vessel was going, with every noise causing imagination to become excessive and untrammelled.

The ship’s Surgeon was Jason Lardner and part of his journal for this voyage of 113 days read “Between 4 and 11 August 1843, 204 female convicts, 24 children and 4 male and 15 female warders were embarked. Many of the convicts were debilitated but none had to be refused. They were washed and issued with clothing; their own clothing being taken away.

Although there were a great many cases on the list, most were trivial. The synochus cases were mostly slight symptomatic affections, arising from ‘suppression of some accustomed evacuation’. None of the vaccinations were successful although two or three trials were made. The unsuccessful atrophy and hydrocephalous cases occurred to very young weakly children at the breast, there was plenty of food for infants. The diarrhoea cases arose from change of food or cold, of the two sent to the hospital, one arose from disordered digestion and had suckled her child the whole voyage. The other was more serious and due to her previously dissipated life.

Scurvy appeared after passing the Cape, the nitre mixture recommended by Dr Cameron was given and every symptom disappeared and six weeks after landing they all remained free from disease. The debility cases were generally from long sea sickness.

The employment of the prisoners during the voyage had the best effects on health and discipline. The surgeon recommends all female convict vessels to be provided with means of employing the prisoners, such as shirt making, with women appointed to cutting out and supervising to prevent wanton waste and destruction of the materials. More than 1100 shirts were made on board during the voyage, the women making on average one shirt a day. Those employed at needlework in the morning read in the afternoons and vice versa.

Sarah (Miles) Jones had very good reason to feel extremely ill, very scared, fearful and awfully worried. She was pregnant and on the 9th November 1843, 66 days into the voyage gave birth to a premature female baby who lived for just 24 hours. Sarah remained on the sick list until the 8th of December. Surgeon Lardner placed Sarah on the sick list again on the 19th December for diarrhoea until the 27th December, four days after mooring at Hobart. Surgeon Lardner officially registered the birth and death of Sarah’s female baby on the 12th of January 1844, two weeks after arrival into the port of Hobart.

VAN DIEMEN’S LAND:

Sarah (Miles) Jones arrived in Hobart at the time the methodology of integrating convicts into everyday life was being quite drastically changed. The methodology from the early days of the colony was relatively unstructured: all female convicts on arrival were assigned to “masters” as domestic servants. If all went well, they remained: some female convicts remained with the one master for their entire sentence. But if they committed an offence the master or mistress considered serious, such as insolence, neglect of work, getting drunk or being absent without leave, they were taken before a magistrate and tried. They were acquitted, admonished or punished by being sent to a female factory and either serving a term in Crime Class or serving a sentence in solitary, sometimes on bread and water. Many female convicts on assignment learnt domestic skills which were useful to them in later life, either earning a living or running their own homes. However, without the protection of their family and with little protection by the state, they were also vulnerable to abuse, mental or physical. Many became pregnant, voluntarily or involuntarily. An Assignment Board was appointed in 1826 to manage the process of assigning convicts to settlers which enabled much better record-keeping.

This system was changed in 1843/1844 to a Probation System for female convicts, a few years after it had been introduced for male convicts. Instead of being assigned on arrival to work for settlers, a female convict served a term of probation (the length depending on her sentence), during which she was given moral and religious instruction, and taught domestic skills as required for cooks, laundresses, and servants. At first convicts spent the probation term on the hulk Anson and, after its disbandment, at the New Town farm station. After serving her term of probation and in theory at least being ‘reformed’, a female convict worked for a master or mistress as a passholder. After some time, and if “well behaved” she could apply for a ticket of leave, then a conditional pardon.

The Anson is a familiar and very interesting ship. One of the two men apprehended and charged with Sarah was Thomas Allison, who was transported to Van Diemen’s Land from Plymouth on board the Anson on the 23rd September 1843. It was a much bigger ship than the Woodbridge weighing 1,742 tons and it was the largest convict ship to arrive in Australian waters, transporting 499 convicts as well as 326 crew and guards.

On arrival in Hobart, Anson‘s rigging and other equipment was sold for £12,307. Anson would never again set sail. She was refitted to become a ‘prison hulk’ of sorts and towed to Prince of Wales Bay on the river Derwent near Hobart. The Anson was used to accommodate and train female convicts from 1844 to 1849 as a Probation Station. Once they had satisfactorily served six months’ probation they were hired into service as probation pass holders. More than 4,000 women were processed and trained on the Anson between 1844 and 1849.

Sarah (Miles) Jones was probably initially sent to the Cascades female factory rather than the Anson and we see from her convict record that at some time in 1844 she is working for a merchant, Mr. William Watchorn as a domestic servant in his home. Watchorn owned Watchorn’s Emporium on Liverpool Street, Hobart and had been living in Hobart with his wife and children for almost twenty years. He was elected as an Alderman in January 1853 and died a year later after a short 3-day illness.

Sarah Jones convict record on arrival in Hobart describes her as:

a housemaid by trade,

4 feet 11 ¼ inches tall,

aged 20,

dark complexion,

oval head,

long visage,

medium forehead,

brown hair and eyebrows,

hazel eyes,

medium length nose and medium width mouth and a small chin.

Sarah had a freckled face but no other marks.

Sarah could read only, and her native place is stated as Bath.

It also mentions that she was ‘12 months on the town’.

Irrespective of the change of entry system from “assignment” to “probation” in Van Diemen’s Land, Sarah had to adjust and assimilate as best she could. Thousands of miles away from her family, knowing that they would probably never know what had happened to her would definitely cause a high level of homesickness. Having two pregnancies as a single woman in her teen years would also produce some angst and self-doubt. Having a son who was being raised by her sister and facing the probability that she would never see him would increase her regret. Delivering a baby girl on a convict ship in the middle of an ocean and being unable to prevent her death would be a direct cause of severe depression. Sarah would have been in a very dark place during the months of assignment/probation she experienced in Hobart, a convict town that would not have been familiar in any substantial way.

Yet her convict and muster record from Hobart shows that she was a good person who exhibited good behaviour.

- On the 5th of July 1844 she is listed as 2nd Class*

- While working for Watchorn her convict record says: “A record made in this woman’s favour for her good conduct whilst in W. Watchorn’s service 29th October 1844”.

- On the 7th of January 1845 she is listed as 3rd Class*

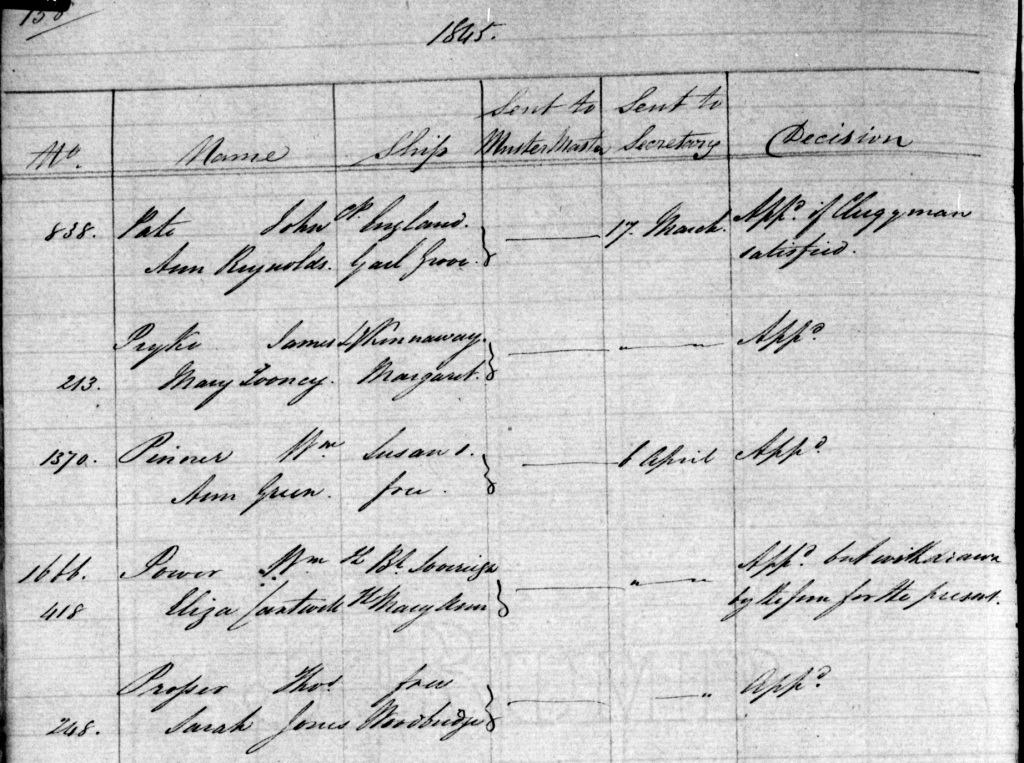

- In April 1845 she and Thomas Prosser have been given permission to marry

- An 1846 Muster shows Sarah as married to Thomas Prosser

- Only one offence is noted – a 5 shilling fine for using obscene language – dated 21 August 1848. The magistrate’s initials for this offence were RCG which was Ronald Campbell Gunn, he was then based in Launceston. This clearly shows that Sarah and Thomas Prosser moved to Launceston between 1846 and 1848.

- Sarah’s Ticket of Leave was granted on the 19th of November 1850,

- Sarah’s Conditional Pardon was approved on the 31st of May 1853.

- Sarah’s 15-year transportation sentence expired in 1858.

*NOTE: Female convicts were expected to work and to complete set tasks whilst imprisoned. 1st Class could be employed as cooks, task-women, wards-women, hospital attendants, or in any other manner as directed by the Principal Superintendent of Convicts. 2nd Class could be employed in making clothes for the Factory, in getting up linen, or in any other manner as directed by the Principal Superintendent of Convicts.3rd Class could be employed in washing for the Factory, the Orphan Schools, or Penitentiary, in carding wool, spinning, or in any other manner as directed by the Superintendent of Convicts.

Any prison system is designed to break every prisoner’s resistance so that they become pliable, manageable and respond immediately to authority. All sorts of wonderful weasel words are touted about the positive aims of incarceration but the reality of a penal system is that a prisoner, somewhere along his or her sentence will resolve to behave in a manner that will allow them to be released from their prison. The behavioural indoctrination while in prison and society’s attitude to a released convict are the factors that give rise to the aphorism “90% of first-time prisoners will go back in a second time and 100% of second-time prisoners will go back in for a third time”.

It is impossible to accurately determine Sarah’s state of mind or behavioural rationale during any part of her life. However, my sense is that she was a very strong woman, courageous and brave.

By April 1845 Sarah (Miles) Jones, contemplating marriage to Thomas Prosser after what her life is, and has been, for the previous six years must have had some kernel of hope, some belief that life could or would get better.

MARRIAGE, FAMILY AND LIFE IN TASMANIA:

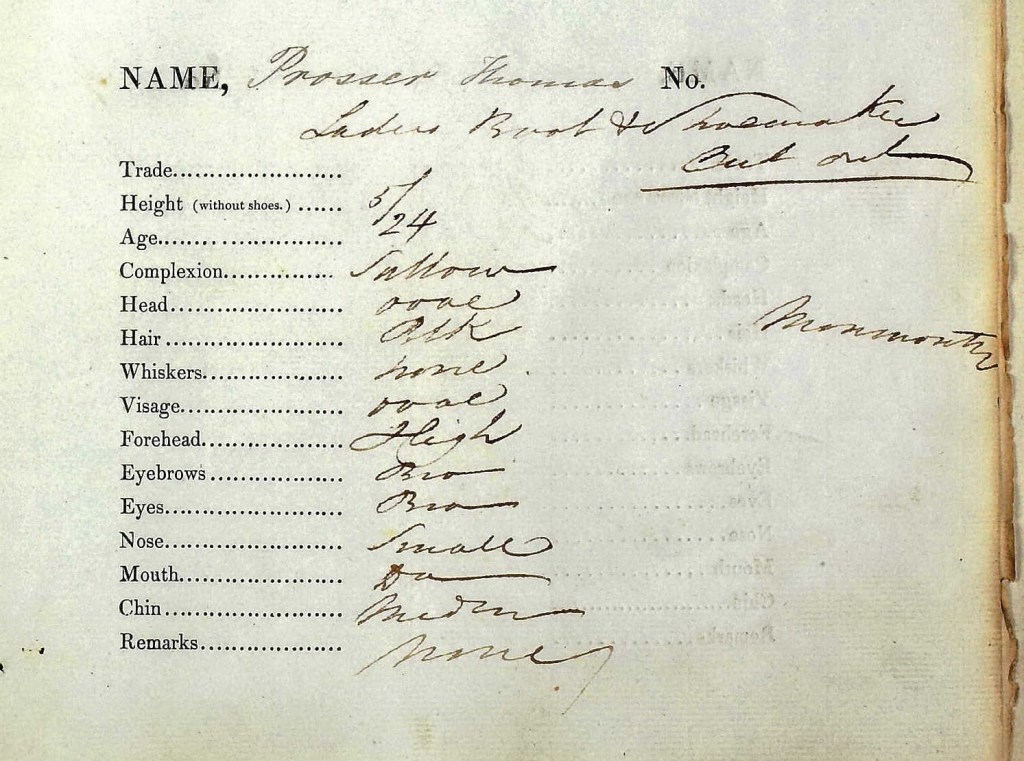

Who was Thomas Prosser?

The background of Thomas Prosser is incomplete and unverified. It seems that tracing his background may be as difficult as it was for Robyne Kirsch to trace and find the details of Sarah Jones/Miles. When he was apprehended and entered into the “legal system” is where our information about him becomes clearer and verifiable. Thomas Prosser was from Monmouthshire in Wales, born about 1816. In 1837 he and an accomplice, Emma Miller were apprehended, tried and sentenced to seven years transportation for the theft of boot fronts and leather blocks, the goods of Joseph Poole. The theft took place at Poole’s shop in Broad Street, St. Giles London on the 14th September 1817.

Their trial, just like Sarah’s was at the Old Bailey and consequently we have a full record of the trial. Posser and his accomplice were apprehended on the 14th September 1837 and went on trial four days later on the 18th September 1837 where they were both found guilty and both sentenced to seven years transportation. The judge was A.S. Laing Esquire.

This is the proceedings from the Old Bailey:

2196. EMMA MILLER and THOMAS PROSSER were indicted for stealing, on the 14th of September, 8 pairs of fronts for boots, value 7s.; and 61bs. weight of sole leather, value 10s.; the goods of Joseph Poole.

JOHN BARFIELD. I am in the employ of Joseph Poole, a currier and leather cutter, in Broad-street, St. Giles. On the 14th of September I saw the two prisoners in the shop—they came in about a minute after one an other—the woman came in first—she bought a few articles, which came to about 6d., and then the man came in—he went up by the side of Miller—a young man beckoned me into the street, and told me something—I went to go back into the shop, and the woman was coming out—I do not know whether Prosser had said anything to her—he bought some things—they were close together in the shop—Miller was then going out, and I asked her what she had got—she said, “Nothing”—I said, “I must look and see”—I and another man opened her cloak, and found on her 8 pairs of fronts for boots and 61bs. weight of sole leather—nothing was found on the man.

Prosser. I paid for what I bought in the shop.

ROBERT BUGO . I was in the shop—Prosser asked for some unblocked fronts—he put them on one side, and the woman put them under her cloak—I am sure of that—I told what I saw—they were not both taken, only the woman—the man slipped by, and went out directly—I am sure I saw him take them, and hand them to the other.

Prosser. We cannot go into a shop to buy leather without looking at it, and no customer can find what suits them till they take the things and lay them on one side; I bought a pair of blocked fronts; what he showed me did not suit me.

THOMAS GREEN. I am a policeman. I took the woman into custody on the 14th, and the leather was given up to me.

SAMUEL BROWN (police-constable G 88.) I apprehended the male prisoner at No. 3, Finsbury-market—he was not locked up till I made further inquiries about it—I said nothing to him about this.

GEORGE WADDINGTON. I am an officer. Prosser was once in my custody—Miller came to see him, and brought him refreshment, and when she was taken I knew that Prosser was wanted—I gave information to the police.

Miller. I am innocent of it.

Prosser. I have dealt with Mr. Poole nearly three years, and never had a stain on my character.

MILLER— GUILTY . Aged 21.

PROSSER— GUILTY .* Aged 22.

Transported for Seven Years.

Thomas Prosser was then detained on the Thames River hulk ship Justitia, the record from that convict holding pen says that he was 22 years old, his crime was larceny, he was convicted on the 18th September 1837 at the Central Criminal Court and sentenced to seven years transportation.

The record also states that Thomas Prosser could read and write, was married, his wife named Elizabeth with one child and prior to being sent to Van Diemen’s land on the 27th October 1837 he had spent 2 months in Bridewell. Bridewell was an established prison in London, a part of Henry VIII’s old palace. “Bridewell” was also a generic term for an open prison for “misdemeanours” where relatives could visit and bring food to the prisoners. There is no other reference to Bridewell in relation to Thomas Prosser. It could mean that he was held at London’s Bridewell prison after sentencing at the Old Bailey and before being taken to the Moffatt, the convict ship that he and 400 others were loaded onto for transportation to Van Diemen’s Land.

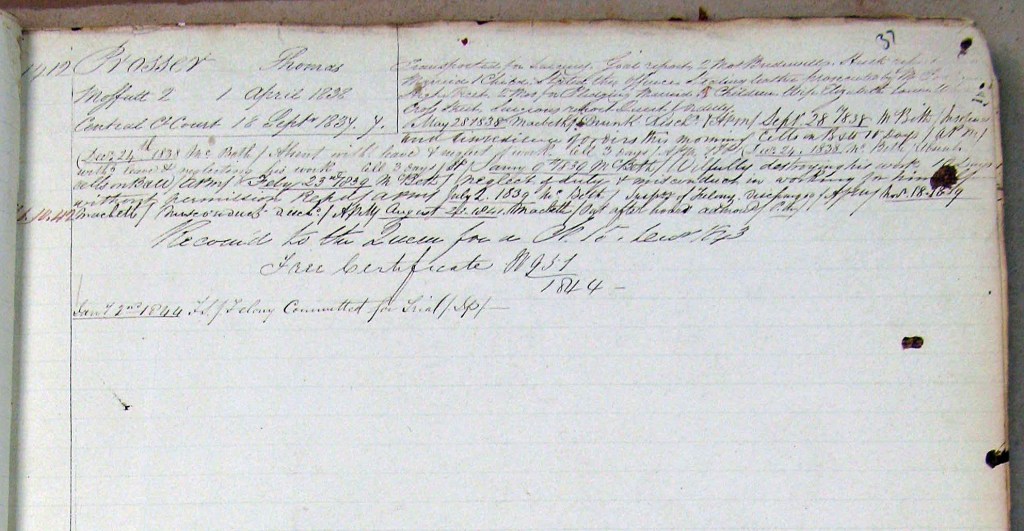

The convict musters and records for Thomas Prosser listed the following:

- The Moffatt departed from Sheerness on the 9th November 1837

- The Moffatt arrived in Hobart on 1st April 1838

- He had previous offences against property – states that he spent 2 months for Pledging.

- He was exactly 5 feet tall, brown eyes & eyebrows, black hair, no marks or tattoos, a sallow complexion, an oval head, no whiskers, a high forehead, a small nose.

- The Ships Surgeon reported that he was put on the sick list on the 18th November 1837 for Psora – a disease of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. He was taken off the sick list on 2nd December 1837.

- He was classified as a Ladies Boot & Shoemaker cutter.

- He was assigned to a Mr. McBeath, a cordwainer in May 1838.

- He was reported as being drunk and sentenced to 3 days in the cells in September 1838.

- He was reported for being absent for leave and neglect of duty sentenced to 3 days in cells in December 1838.

- He was reported for wilfully destroying his work and sentenced to 10 days in cells with ball in January 1839.

- He was reported neglect of duty and misconduct in working for himself without permission in February 1839.

- He was reported by McBeath for suspicion of felony, discharge of duty in July 1839.

- He was reported by McBeath for misconduct in November 1839

- He was reported for misconduct and dereliction of duty in August 1841

- He was given his Ticket of Leave on 6th October 1842.

- Recommended for Conditional Pardon on 21 November 1843.

- Given his Ticket of Freedom on 18th September 1844.

This is quite a different record in comparison to that of Sarah Jones. The muster and convict records show that Sarah was considered well behaved and Thomas possibly better than average – it must be noted that at no point in his term was Thomas flogged.

It seems that Thomas railed against the system upon arrival in Van Diemen’s Land or he had quite a conflict with McBeath, the cordwainer that he was assigned to. The details are sketchy because the assignment records for male convicts for the period 1836-1844 are missing, however it seems that after a few years Thomas Prosser accepted his fate or realised that he would be better off by “behaving” to secure his Ticket of Leave, Pardon and Freedom.

One point of interest in Thomas Prosser’s ordeal is that his accomplice, Emma Miller somehow “disappears” from all records after sentencing and close examination of all female convicts to Australia suggest that she did not serve her seven years transportation. Perhaps we will never know what happened to her.

In April 1845 Prosser and Sarah Jones/Miles are given permission to marry and on the 28th April 1845 they were married at St. Georges Church of England in Hobart.

SARAH’S CHILDREN:

As outlined earlier, Sarah and Thomas located to Launceston sometime between 1846 and 1848 probably to begin their own cordwaining business in a place well away from Hobart. They remained in Launceston until their deaths and had a family of fourteen children. Tragically, only six of these children survived beyond childhood.

Emma Prosser: 1845-1853

Born in February 1845, before Sarah and Thomas were granted permission to marry. No birth or baptism certificate has been found and this date of birth is calculated from the death certificate – District of Launceston deaths number 916.

Elizabeth Prosser: 1847-1849

Born in July 1847. No birth or baptism certificate has been found and this date of birth is calculated from the death certificate – District of Launceston deaths number 71.

Thomas Prosser: 1849-1879

Date of birth written on the baptism certificate – 19th August 1853 Holy Trinity Church Launceston number 760. District of Launceston deaths number 525.

Sarah Prosser: 1851-1851

Date of birth written on the baptism certificate – 27th December 1851 Wesleyan Church Launceston number 701. District of Launceston deaths number 495.

John Prosser: 1852-1852

Births in the District of Launceston number 3625. District of Launceston deaths number 635.

Walter Lewis Prosser: 1853-1854

Date of birth written on the baptism certificate – 19th August 1853 Holy Trinity Church Launceston number 759. District of Launceston deaths number 1278.

Walter John Prosser: 1854-1930

Date of birth written on the baptism certificate – 5th October 1854 Holy Trinity Church Launceston number 871. Death date 13th March 1930 from Carr Villa Cemetery Records, Launceston.

Sarah Prosser: 1856-1857

No birth or baptism certificate has been found and this date of birth is calculated from the death certificate – District of Launceston deaths number 229.

Lydia Prosser: 1857-1938

Births in the District of Launceston, No. 1263. Unnamed baby incorrectly listed as ‘Male’. Baptised 3 Dec. 1857, Holy Trinity Church Launceston as Lydia, date of birth on baptism certificate is 9 Nov.1857 which matches birth certificate. Death date 5th March 1938 for Lydia Doney from Carr Villa Cemetery Records.

John Charles Prosser: 1859-1859

No birth or baptism certificate has been found and this date of birth is calculated from the death certificate – District of Launceston deaths number 450.

William Prosser: 1860-1957

Date of birth written on the baptism certificate – 3rd January 1861 Holy Trinity Church Launceston number 1434. Death date 19th September 1957 from Carr Villa Cemetery Records.

Arthur Albert Prosser: 1863-1922

Birth 21st March 1863 in the District of Launceston number 164. Death date (13th February 1922) from The West Australian 14th February 1922.

Louisa Kate Prosser: 1864-1907

Date of birth written on the baptism certificate – 5th February 1865 Holy Trinity Church Launceston number 1795 as Kate Louisa Prosser. Death date (19th May 1907) from Daily Telegraph, Launceston, 20th May 1907.

Edwin Miles Prosser 1866-1867

Date of birth (1st February 1866) written on the baptism certificate – Wesleyan Church Launceston, 8th April 1866 number 6000. District of Launceston deaths number 247. Edwin’s name incorrectly written as Edward.

Tasmania during the 1840’s and the 1850’s experienced a period of unemployment and associated economic depression as the effects of the abolition of the convict system were felt. There was a great reduction in government funds for training and assignment of convicts and an oversupply of labour from free settlers, freed convicts and convicts. Launceston, where Thomas and Sarah had settled experienced this downturn more acutely than Hobart, however the whole state was in a recession until gold was discovered in Victoria. By the 1870’s Melbourne was one of the richest and vibrant cities in the world and Tasmania benefited from gold fever by the supply of food, tools and equipment. Despite this boom across Bass Strait, life in Launceston for former convicts in the cordwaining business would not have been easy; and the loss of so many of their children must have been devastating and extremely demoralising.

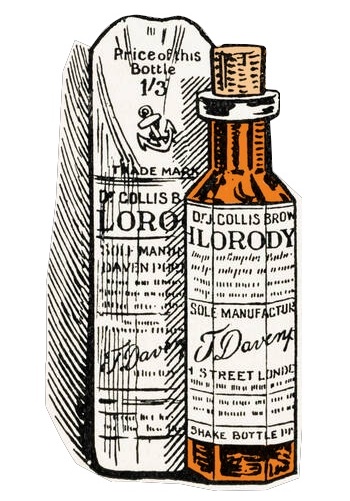

Sarah and Richard were living on Wellington Street, Launceston for most of their married life; and Sarah died on the 9th of May 1883 at the age of 59. An inquest determined that Sarah had taken a dose of Chlorodyne in an attempt to get some sleep. Chlorodyne was formulated by a Doctor John Collis Brown who was trying to find a remedy for cholera when stationed in India in 1848. He sold the formula to a London pharmacist who manufactured and promoted it throughout the English speaking world. . It was heavily marketed as a wonder drug that would treat coughs, consumption, diphtheria, diarrhoea, neuralgia, epilepsy and of course, cholera. The ingredients were chloroform, morphine, cannabis and laudanum, quite a combination for a small woman almost 60, probably suffering fatigue and depression. Although Chlorodyne sales contributed to a rise in accidental overdose and addiction, the ‘therapeutic’ use of opiates was largely unregulated at the time. Manufacturers didn’t even need to list ingredients and it is thought to be responsible for the death of people in Australia at this time, particularly children who were given the “medicine” as a cure for diarrhoea.

Thomas Prosser died three years after Sarah, on the 21st of April 1886 at the age of 70. Both Sarah and Thomas were buried in the Cypress Street Cemetery, Launceston, which now lies under a school sports ground.

WHAT BECAME OF SARAH’S ACCOMPLICES?

The other Sarah, Sarah Fuller who was also transported to Van Diemen’s land on board the Woodbridge had a similar path to Sarah Jones/Miles. She married a Richard Drought, an Irishman from Dublin who had been sentenced to seven years transportation for larceny. He arrived at Van Diemen’s Land on board the Prince Regent in 1841 and gained his Ticket of Leave in 1845; and then his Certificate of Freedom in August 1858. Richard and Sarah married on the 17th of August 1848 in Campbell Town, which is about halfway between Hobart and Launceston. They had six children. Richard died about the year 1900, possibly in Devonport and Sarah was living on Wellington Street, Launceston when she died in 1911.

Thomas White seems to have been named Joseph White in some records and consequentially his fate is somewhat blurred. He was sentenced to transportation for life and was sent to the colonies on board the Maitland, one of twenty-one ships that transported convicts from Britain to the Australian colonies in 1843.The Maitland sailed from Portsmouth on 26 August carrying 200 men, 167 sentenced to life and the others with an average sentence of 20 years. The ship initially landed at Sydney, but the records show it docked at Norfolk Island on 7th February 1844, where 200 prisoners were disembarked and 338 prisoners who had already been serving sentences in Norfolk were then trans-shipped to Hobart. I can find no trace of a Thomas or Joseph White in Sydney, Norfolk Island or Van Diemen’s Land.

Thomas Allison, 22 years old from Spital Fields in London was sentenced to fifteen years transportation and arrived at Van Diemen’s Land aboard the Anson. I mentioned this ship earlier: it was stripped and the rigging and other equipment was sold for £12,307. Anson would never again set sail. She was refitted to become a ‘prison hulk’ of sorts, towed to the Prince of Wales Bay on the river Derwent near Hobart and used to accommodate and train female convicts from 1844 to 1849 as a Probation Station.

Thomas Allison in my view then became a convict who railed and fought the penal system every step of the way. His record sheet is the most extensive I have seen. He is a regular absconder, at least ten times and sometimes across Bass Strait to Victoria. He adopts aliases to prevent recapture. He even absconded from the Constables Station near Eagle Hawk Neck! The records show that he was denied permission to marry Elizabeth Brown in 1852, and that he did gain his Ticket of Leave in February 1858.

He is worthy of a story on his own: I hold great admiration for the flawed rebels of society.

A CONCLUSION:

Firstly, and most importantly I would like to acknowledge and thank Robyne Kirsch, a 3rd great granddaughter of Sarah Miles / Jones / Prosser who was responsible for the difficult and insightful genealogical research which enabled the story of Sarah to come to light.

Robyne knew that Sarah (Jones) Prosser was her great, great, great grandmother and could research her life from apprehension and sentencing in London to her death in Launceston. Finding Sarah’s birth and family proved to be much more difficult but with great perseverance and determined “sleuthing” Robyne successfully pieced together Sarah’s background in rural Somerset.

Key to the unravelling of Sarah’s background was the information recorded about most convicts from trial and sentence to conduct as a convict and their possible freedom. On a website https://www.digitalpanopticon.org all available convict records have been assimilated into the “Van Diemen’s Land Founders and Survivors Convicts 1802-1853” which is a consolidated database of evidence from numerous original sources. It provides a mass of information on the Old Bailey convicts who were ultimately transported to Van Diemen’s Land (along with those convicted at other courts throughout the British Empire).

The project draws on over 1.5 million digital records covering populations who either migrated to the British colony of Van Diemen’s Land (renamed Tasmania in 1856) or were born there in the years 1803-1900. Many of these are linked to digital images of the original documents. The record groups covered by the project include a number of series relating to transported convicts that have been provided to the Digital Panopticon. These have also been linked through to the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office “Tasmanian Name Index”.

The original convict record series held by the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office (TAHO) were created in the period 1824-1870. However, they also include much information retrospectively entered from earlier record groups. The 522 volumes of records in the collection were placed on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in 2007

The data extracted from the record series ranges widely and includes:

- Police number, ship and date of arrival.

- Physical descriptions, colour of eyes, hair, age on arrival, height, scars, tattoos and other marks.

- Information about place of birth and next of kin.

- Details on where convicts were sent to work on arrival and subsequent transfers.

- Information about monies and property brought to van Diemen’s Land.

- Conviction data including confessed convictions, transportation offence and colonial convictions.

- Information about tickets-of-leave, certificates of freedom and pardons.

- Applications for permission to marry.

- Information about deaths under sentence.

- Government Gazette runaway notices.

- The Tasmanian Police Gazette: notices of convictions and discharged prisoners.

- Tasmanian departure records.

- Pauper records.

- Convict musters.

- Diagnostic data recorded in Surgeon Superintendents journals.

- British hulk records.

This has resulted in a very comprehensive database, available online and easily searchable. Complete data for every person convicted and sent to Van Diemen’s Land is in some cases missing or illegible.

From these records Robyne established that Sarah Jones was born about 1825 and came from Bath, Somerset. She found that Sarah’s father was John, living in Bath; she had 5 brothers, John, Charles, Richard, John and Isaac; and 2 sisters, Ann and Eliza. Good information, but a lot of searching was still needed to determine any possible family connections, especially with a surname “Jones” and Bath being a short distance from Wales where “Sarah Jones” would be ten to twenty times more prevalent than Sarah Miles.

Robyne found that where there was provision for the mother’s maiden surname on Sarah’s children’s birth certificates, it is stated as Miles.

Sarah’s last child, Edwin, was given the middle name of Miles.

Sarah’s daughter Lydia named her first child Constantine Miles Prosser.

This research was supported by descendants DNA testing which confirmed that Sarah Jones, female convict from the Woodbridge in 1843 is the same person as Sarah Prosser nee Miles who was married to Thomas Prosser, shoemaker.

Robyne also found in her research that Sarah (Miles) Prosser had a younger brother, John Miles (1826-?) who was convicted of theft in Somerset and sentenced to transportation to Van Diemen’s Land, arriving on the convict ship Marion in June 1845. We think that he did not marry, nor have children and may have spent the rest of his life in Van Diemen’s Land ………… or he might have left Van Diemen’s Land as soon as he was given his freedom for the colonies across Bass Strait, married magnificently and had a brood of healthy loving children.

Perhaps a future generation of family historians will add some flesh to his bones.

** ** ** **

Robyne Kirsch is a 3rd great granddaughter of Sarah (Miles) Prosser.

Vicki Miles is a 3rd great niece of Sarah (Miles) Prosser.

Frances (Miles) Nelson is a 3rd cousin, twice removed of Sarah (Miles) Prosser.

Vicki Miles and Frances (Miles) Nelson are 5th cousins, twice removed.

Robyne Kirsch and Vicki Miles are 4th cousins once removed.

Frances (Miles) Nelson and Robyne Kirsch are 5th cousins, three times removed.

** ** ** **

SOURCES:

There are so many sources that I’ve utilised to both achieve accuracy and to add humanity where I think it was appropriate and suitable.

This is an account of family history, researched and written for our families benefit, value and enjoyment.

This story could not have been written without the magnificent work of Robyne Kirsch as I have acknowledged above; and Vicki’s Somerset cousin, Frances (Miles) Nelson.

All manner of information from all sorts of books from our library and the libraries of others have contributed to this story and I invite those interested to spend some time in those libraries.

In no particular order here are (most) of the online sources that I utilised:

https://www.digitalpanopticon.org

https://www.hsomerville.com/meccano/Articles/JacobsIsland.htm

https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp01949/sir-john-gurney

https://www.thehistoryoflondon.co.uk/category/history/london-mid-19th-century

https://alondoninheritance.com

https://www.londonlives.org/static/OBP.jsp

https://www.londonhistorians.org/?s=links

https://www.batharchives.co.uk

https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol4/pp65-91

https://www.walkingenglishman.com/outandabout/southwest/06englishcombe.html

https://highlittletonhistory.org.uk

https://londonist.com/london/oldmaps

Leave a comment