It was an article about Archibald Miles in the Bath Chronicle just ten weeks after the start of the “Great War” that initially attracted Frances Nelson’s attention. During the four-year conflict, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire (the Central Powers) fought against Great Britain & its Empire, France, Russia, Italy, Romania, Canada, Japan and the United States (the Allied Powers). Thanks to the horrors of trench warfare and new military technologies, including tanks, airplanes, submarines, machine guns, modern artillery, flamethrowers & poison gas, World War I saw unprecedented levels of carnage and destruction. By the time the war was over and the Allied Powers had won, more than 16 million people—soldiers and civilians alike—were dead.

In August 1914, both sides expected a quick victory. Germany’s initial aim was to remove the French out of the war by occupying Belgium and then quickly march into France and capture Paris, allowing their troops to concentrate on the conflict in the east. That plan failed, and by the end of 1914, less than 100 days after the following article, “The Gallant Somersets” was published the two sides were at a stalemate. They faced each other across a 175-mile-long line of trenches that ran from the English Channel to the Swiss border. Many expressed that what they were experiencing was not war, but mass slaughter.

Frances Nelson was born a Miles and is a 3rd cousin 1 X removed of Archibald John Miles, the bandsman from Bath who is central to the story “The Gallant Somersets” published on Saturday 26th September 1914.

Her research uncovered a family of military musicians from Taunton, six of whom served during WWI – one was killed in the trench warfare of Flanders.

Frances and Vicki are 5th cousins 2 X removed;

Archibald and Vicki are 4th cousins 3 X removed;

This is the article, published a few short weeks after the formal declaration of war:

The Bath Chronicle, Saturday September 26th 1914

THE GALLANT

SOMERSETS

A BATH BANDSMAN’S STORY

HOW THE WOUNDED GOT BACK

Further evidence of the distinguished part which the 1st Somersets played in the fighting in northern France continues to be received. Among those who returned to England wounded was Bandsman Archibald Miles, fourth son of Colour-Sergeant Miles, assistant master of the Sutcliffe School, Bath. He is now happily recovered, and is about to return to Taunton, as the depot of the county regiment. It was Bandsman Miles’s duty to act as stretcher bearer. The Somersets, as is now well-known, shipped to France and landed at – not Boulogne. That night and all the next day, they spent at a rest camp until about midnight, when they were marched off to a railway station, and began an 18 hours’ ride northwards. The railway ride came to an end about six o’clock in the evening, and the men had a chance of straightening their legs, for they were marched off a distance of from 12 to 15 miles, and it was midnight when they halted for a rest. This was in a village, where some of the men were billeted in barns, and other buildings, the rest having to sleep in their great coats as best they could upon the open green. Fortunately the weather was rather warm. Of course, sentries were sent out in case of any prowling Uhlan patrols being in the neighbourhood. Other troops followed after the Somersets. Bandsman Miles thinks they must have been other portions of the 11th Brigade, but he cannot be certain.

After about six hours rest the Somersets formed up about six a.m., and marched about a mile out of the village, picking up their patrols as they went. The Somersets got down in a dip and proceeded to entrench themselves. Meanwhile the East Lancashire Regiment came up from behind them, but passed on ahead to take up a position.

ARTILLERY DUEL CAUSES RAIN.

“I suppose it was the artillery fire going on that brought down the rain” continued Bandsman Miles. “We could see an artillery duel going on in front of us, about five or six miles ahead. The rain came on, and it came down pretty thick. But our men would not be done, and while it was raining they took off their shirts and went on digging the trenches. They had nothing on but their trousers, boots and stockings; and thus stripped to the waist. You could see the steam coming from their bodies as they worked away. We put the barbed wire entanglements about 50 yards in front of the trenches in case of any cavalry attacks. We were quite surprised to find afterwards that our cavalry division were not scouting in front of us. The first intimation we had of that fact was seeing them return. We asked one or two if they had had any luck, and they said “No.”

A SURPRISE FOR THE GERMAN AIRMAN.

“There was a German aeroplane coming across towards us. It was flying rather low, and the airman probably had not seen us. Our headquarter company let go a volley at the aeroplane, and I think some of the shots must have penetrated the wings. At any rate, the airman realised his peril, for he planed sharply upwards well out of range, and then curving round in a wide sweep he went back to whence he had come.”

“It would be about three in the afternoon when we saw the aeroplane, and nothing of note occurred until about midnight. Then there must have been a patrol of Uhlans in our vicinity, because all our men opened fire. After that we were not disturbed again, so we retired from that position, covered by our own supports who were entrenched behind us. That was about two o’clock in the morning.”

“We returned to the village which we had left in the morning, and found our cavalry already billeted there. We slept as best we could for three or four hours, and then we had an all-day march. We were retiring; and about midnight we got to a town – which may have been Cambrai. Whatever town it was, we stayed there until six in the morning, and then resumed our march. We had just got to the other side of the town, when one of the staff officers came up, and told us to return to the town.”

A REARGUARD ACTION.

“The Rifle Brigade which was doing rear-guard, had been attacked, and we had to return to support them. Our regiment was then divided – one half battalion was split up into platoons, which were sent along different streets to prevent the enemy’s cavalry coming down them. Those troops started firing as they went through the streets of the town towards the open country beyond. Meanwhile the other half battalion of ours marched off to take up a position outside the town, passing in rear of the Rifle Brigade, and eventually coming into line with them on their left.”

“We had taken all our supports outside the town, into a dip about 80 yards wide. This was a long ditched-shaped depression, and it afforded natural protection, a bank about 9ft. in height being between us and the firing. Men from our half battalion had gone to fill up gaps in the Rifle Brigade and these had got into the firing line before the enemy located us in the dip, and began to drop shells near us. As men were hit out in the firing line, we got them back to the shelter of the dip, and more supports went up to take their places. The enemy observed these movements, and their artillery sent about a dozen shells at us. The first shells went over us, but eventually the range was brought down until the shells pitched two or three feet from the edge of the bank beyond which we were sheltered.”

DESTROYING A FARMHOUSE.

“Just in front of the dip, and affording useful cover for our supports to rush up to the firing line, stood a little farmhouse. A couple of German shells at the farmhouse levelled it to the ground; and after that, as the supports went up, the enemy’s shells dropped among them. We got a lot of wounded back, some so badly hurt that we had to leave them when we retired, as we had lost our Maltese cart with the stretchers in. Only those wounded who were able to walk got back with us.”

“Eventually the order came for us to retire. All this time I had been in the dip, except when I was called towards the firing line to bandage wounded men and to bring them back under cover to the dip. My brother Gilbert and I were working together attending wounded men when the order for retirement was given. There was a roadway leading from the enemy towards the dip, and the enemy must have had a maxim gun trained down the road, for bullets came flying along. We had to cross the road in order to get out of our part of the dip, and into the dip again on the other side. My brother made a bid to get over the road, and he got across all right.”

ROLLED ACROSS A BULLET-SWEPT ROAD.

“I wondered how I could cross in safety, and eventually I rolled clean across the road and down the bank on the other side. The enemy were now advancing quickly towards us. My brother left me and returned across the road to the wounded and supports we had left. I was now on my own, and made a rush up the bank behind me. Then I had to dash across about 300 yards of a turnip field. As luck would have it, there was a little thicket of green stuff in the field, growing about six feet high, and offering perfect cover. As I made towards it they must have trained the maxim gun on to me, because I hear bullets whizzing by me, and about half a dozen passed between my legs and took the soil up right in front of me. But I reached the green stuff and was lost to sight. Emerging on the far side, the ground fell away again and I was under cover.”

WAITING FOR STRAGGLERS.

“A little distance away was a railway, and our A Company were keeping the embankment until our men had got back or the Germans should come over the dip. Two guns of our artillery were near a village on the left towards which I was making. I caught up with some of our supports. In the meantime the German guns had come round and were in a position almost flanking that occupied by our guns; but seeing our stragglers coming in, the enemy’s artillery shortened range and sent shrapnel on them. Very few of ours, however, got hit: but I was one of the unlucky ones. I got it in the neck, just to the left of the vertebrae. A quarter of an inch nearer the centre would have settled me. As it was I was not hit out, but only numbed for a time, and I made off to the village near our guns, where I got bandaged up. A lot more of our wounded came back there, a house being converted into a hospital. “

“We had a French interpreter there, and after we had been dressed he started to take those wounded who could walk to the rear. On the way we caught up three carts full of wounded – sixteen men and a medical officer. The officer put the carts under my charge, and told me to take them to a station about six miles away.”

RAILWAYS IN POSSESSION OF GERMANS

“When we reached the station we found the lines were occupied by the Germans, so I set off with the carts to the next station, nine miles further on. Just as we got there the Germans had got round the lines, the train had just gone, and there was no other. The stationmaster tried to get a telephone message through to St. Quentin, but all the wires were cut. The French people who were driving the carts were just as anxious as we were to get of the danger zone, so we drove on to another village eight or nine miles back, and there we got to a French hospital. A medical officer saw to the dressings of the men, but four of them were so bad that we had to leave them in the hospital. They were going to put us all up for the night when I saw a lot of our men coming through the village. They told me the Germans were advancing very quickly so I went back to the other wounded and told them it was no good staying. We went on accordingly to another village six miles further back, and there we stayed the night, and there we stayed the night with one of our signalling sections which had been cut off.”

ROUEN – AND ENGLAND.

“In the morning we mustered about 50 men, stragglers and wounded; and the officer in charge of the signalling section sent us back safely to St. Quentin, where the wounded were entrained for Rouen, something like a 16 hours ride. We went into a field hospital at Rouen and were attended to, but had to strike camp, and the hospital, which had been up only two days, had to move further down the country. A doctor came round, and ordered all the serious cases that could be moved to England, me among the number. We embarked on the hospital ship St Andrew at Rouen, and had six hours on the Seine. Then we sailed for Southampton, and I went to London Hospital. I was there just over a week, being treated very well, and then I was sent to Lord Lucas’s estate in Bedfordshire for eight days and then on to Bath.”

“No, I did not see many Bath men about me, but when I was retiring past our A Company at the railway embankment I saw my chum, Bandsman Newman, who comes from Bath. He was very well. It was on my first day in action that I received my wounds, August 26th, and I shall not forget the date, because that just completed my seventh year of service with the Somersets.”

The second sentence of the article identifies Colour-Sergeant Miles, assistant master of the Sutcliffe School, Bath as Archibald Miles’s father, a very good place to begin.

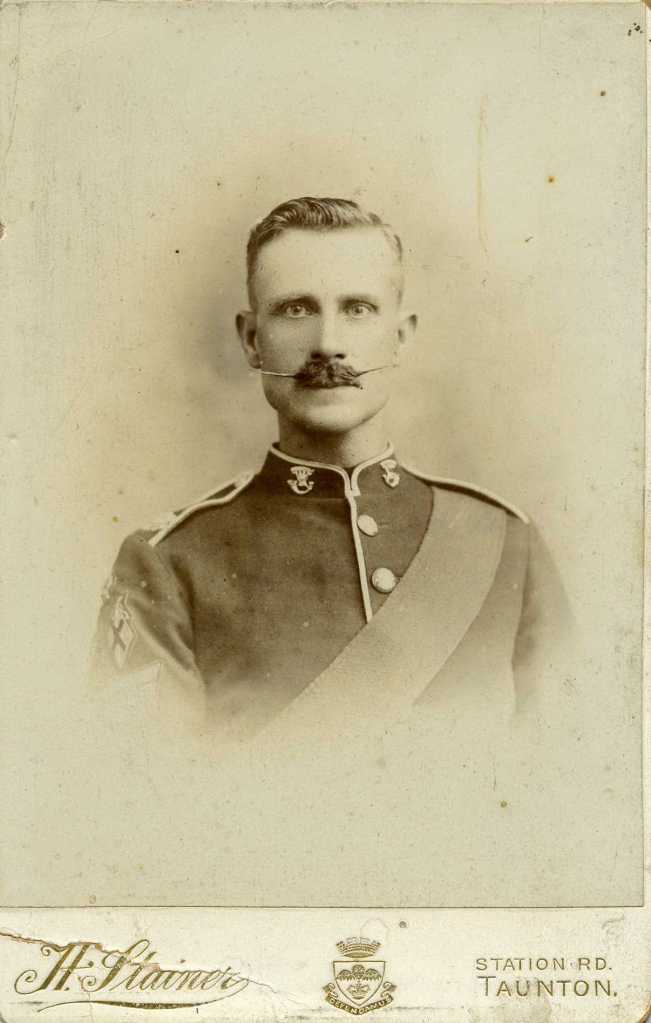

The Colour-Sergeant was a George Miles, born in October 1860, the second son and fifth child of George John Miles (1829) and his wife, Amelia Marchant (1833-1897). His birth was registered in the ward of Lyncombe and Widcombe, part of the city of Bath.

The 1861 Census from Lyncombe and Widcombe shows George as a 9 month old son, his father George (33) a brewers labourer; his mother Amelia (28); a brother Alfred (11) and sisters Selina (9), Ellen (6), and Charlotte (3).

In 1871 the Census is from St. James, Bath and shows George (11) with his parents George (45) a brewer’s labourer and Amelia (38); siblings Charlotte (13); William (8); Martha (6) and Arthur (2).

By the 1881 Census the family is living in the parish of Bath St. Peter and St. Paul. George Snr. (52) is a brewer’s labourer, his wife, Amelia (48); their children Alfred (31) an engine driver; Selina (29) a laundress; Charlotte (26) a seamstress; George (20) is also an engine driver; William (18) a mason’s labourer; Martha (16) a general servant; Arthur (13) a scholar; and Rosina, who is known as Prudence (9), a scholar.

The 1881 Census from Taunton, a town about 50 miles south-west of Bath reveals the Colour-Sergeant’s future wife and her family. Rose Hawkings (21) is a Milliner living with her parents, James (68) and Ann Hawkings (69) at 32 and 33 Tancred St Taunton with her brother, John Hawkings (26) and a niece, Florence H. Hann (6).

Taunton was Rosina’s birthplace however there is no indication as to why George ventured there. Perhaps driving a train? Or maybe he was involved with the military in some fashion – Taunton was the depot for the Somerset Light Infantry but his enlistment is dated 25th May 1886. The enlistment papers do suggest that he was a member of the 4th Somerset Light Infantry, so he could have been in Taunton soon after the 1881 Census in Bath.

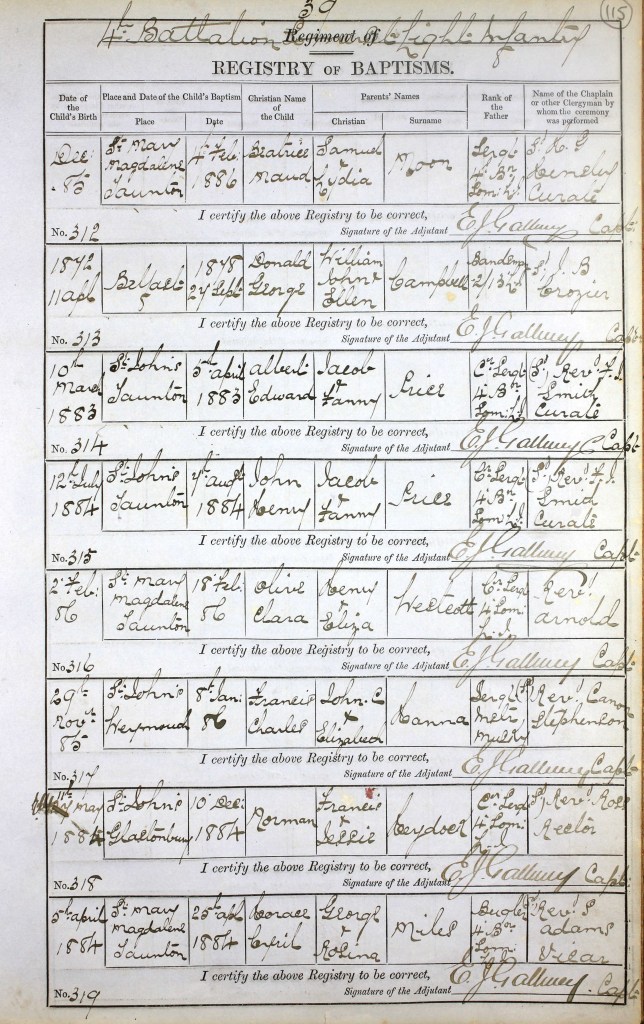

Irrespective of how and where they met, George Jnr. married Rosina Hawkins (1859-1940) on the 18thJanuary 1883 in Taunton, Rosina’s home town. The actual date of the marriage is found in George’s Army Pension Records. Their first born, a son, Horace Cyril Miles was born on 5th April, 1884 and baptised on the 25th April at St Mary Magdalene in Taunton. Horace is also on the 4th Battalion of the Somerset Light Infantry marriage births where George is listed as a bugler. He is noted as a bandsman on the parish record.

A second son, Lionel, was born on 15th April 1886, also in Taunton; and baptised on 15th May 1886, with George Jnr. again listed as a bugler. The parish records show George and Rosina living at 29 Tancred Street with George identified as a musician. As noted earlier, George (Colour-Sergeant) was enlisted into the Somerset Light Infantry as a musician on the 25th May 1886.

Lionel survived only into his second year, being buried in June 1887.

Another son, Clifford George Miles was born on the 21st May 1887 at St. James parish in Taunton. His baptism on the 30th November 1887 is also on the 4th Battalion of the Somerset Light Infantry births registry where George was again listed as a bugler.

On 23rd February 1889, another son, Gilbert Arthur Miles was born in Taunton and then in 1890, the first daughter, Hilda May was born and died soon after. On June 14th 1891 a daughter, Ethel Ida is born. Ethel was born after the 1891 Census which shows the family living at the Taunton Barracks. George (30) listed as a Bugler and Soldier; Rosena (30) wife; Horace (7) son; Clifford J (4) son; Gilbert (2) son.

In November 1891 George was posted to Gibraltar as a Bugler soldier with the Somerset Light Infantry and the whole family went with him.

Gibraltar, that rocky entrance to the Mediterranean, had been a strategic military outpost for the British since 1713 when Spain ceded the territory to Britain under the terms of the Treaty of Utrecht, a consequence of the War of the Spanish Succession fought between 1701 and 1714. The peninsula has evolved from a place of reverence in ancient times into “one of the most densely fortified and fought-over places in Europe”,as one historian has put it. Gibraltar’s location has given it an outsized significance in the history of Europe and its fortified town, established in the Middle Ages, has hosted garrisons that sustained numerous sieges and battles over the centuries. During the 18th and 19th Centuries Gibraltar became a very important harbour which made use of “prisonhulks” which were decommissioned and dismantled warships, stripped of their masts, rigging and sails, and converted into makeshift prisons which could hold well over 500 prisoners at any one time. Originally conceived as a short-term solution to the prison housing crisis in the aftermath of the American Revolution, these floating prisons were moored up in estuaries neighbouring the Royal Naval Dockyards of Portsmouth, Plymouth and the Thames, even as far afield as Britain’s strategic outposts in Bermuda and Gibraltar. As well as providing secure prisons for the hundreds of convicts sent to build the Navy fortresses on both Gibraltar and Bermuda, they were also used as convenient temporary holding quarters for convicts awaiting transportation to Australia and other penal colonies within the British Empire. The hulks formed part of the British carceral landscape for eighty years, with prisoners providing a source of labour for dockyard expansion and repairs. The hulks themselves have gone down in history (thanks to Great Expectations) as “hell on water”.

English Penal system.

In 1891, when George Miles and his family arrived on Gibraltar it was used more for initial overseas training for British troops that were being sent on to other parts of the world. Research has suggested that parts of the 1stSomerset Light Infantry had been posted to Gibraltar before 1881 and that regiments would generally be posted for about 15 years at one place then moved to another. George enlisted in 1886 and many other members of his regiment would have enlisted at varying times suggesting that the 15 year tenure or posting could have been fairly “fluid”.

It is interesting to contemplate the role that George played as a musician in the army.

A bugler was needed to play “commands” in military manoeuvres: things like “attack”, “retreat”, “unleash the cavalry” when small scale battles were being fought, but with armies numbering in the tens of thousands and warfare being a lot more regimented – like the Crimean, or stealthy – like the skirmishes in Africa, the role of the bugler became more ceremonial.

Historically, military bands were funded by the officers of the regiment (a situation that continued well into the late 1800s). A regimental band thus functioned just as much as the officers’ private band, as it did as an element of military ritual and ceremonials. A significant part of its purpose was to play music for the officers’ entertainment in the Mess, and to perform at balls and concerts, and there is plenty of evidence in surviving printed music and in newspaper reports of the period of the kind of music that they played – ‘favourite airs and marches’, ‘reels and country dances’, quadrilles and ‘selections’ from the operatic and classical repertoires being typical. These bands which always had solid percussion foundations would invariably include eight to ten wind instruments – clarinets, oboes, horns, bassoons, a trumpet and a trombone.

Britain had trouble recruiting soldiers into military service in the second half of the 19th century due partly to famine conditions in Ireland and Scotland, and because thousands of single men had migrated to America and Australia in pursuit of the possible riches that the gold rushes promised. A soldier would not been allowed to bring a wife and family with him on overseas postings, but in the case of bandsmen the situation was different. Perhaps the bandsmen were considered more educated or career oriented, but it was quite normal for the British army to facilitate wives and families of bandsmen to accompany them during their military service.

George Miles did not stay long on Gibraltar. Rosina was pregnant when the family left Somerset for Gibraltar and gave birth to yes, another son. On 29th June 1892 the fourth son, the centrepiece of the article published by the Bath Chronicle in 1914, Archibald John Miles was born on Gibraltar. A little more than a year later, on the 19th December 1893 George was posted to East India as part of the 1st Battalion Somerset Light Infantry’s roughly scheduled move after 15 years on Gibraltar. His family travelled to India with him and two more sons were born while he was on duty in the Punjab region of India, a part of India that had become strategically important for the British Army.

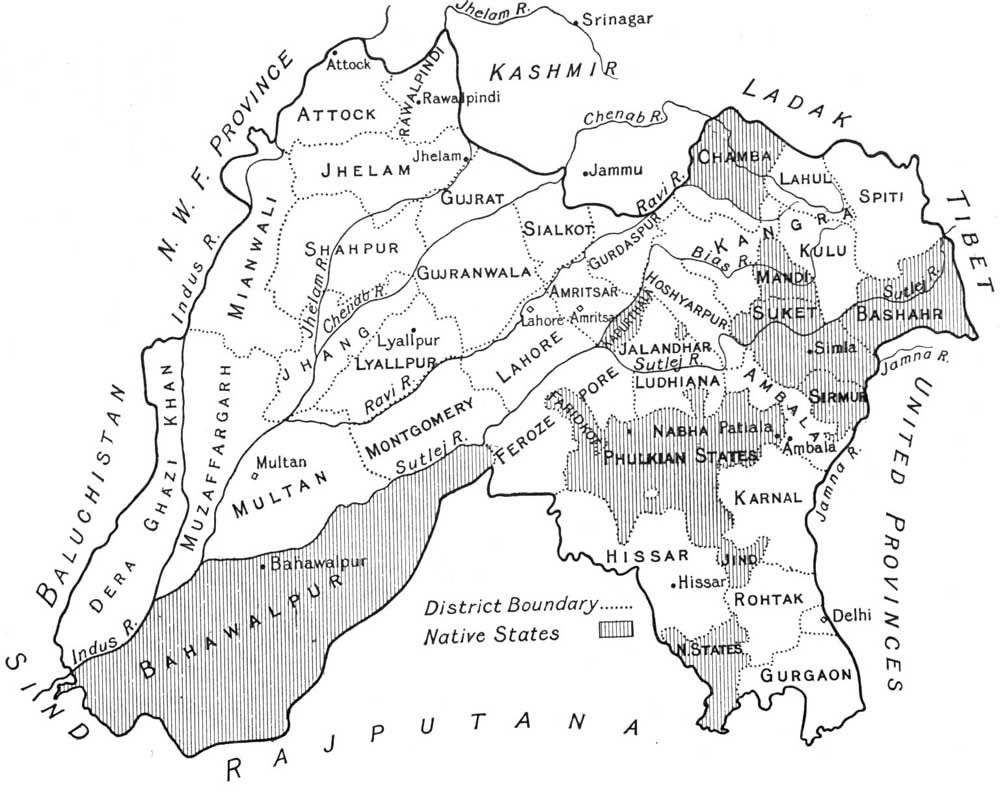

The 1857 Mutiny or the War of Independence in India was a major upheaval for the colonial masters. From the military’s point of view, the main responsible factor in the outbreak of the mutiny was the Bengali soldier. His ethnic majority in the Indian Army and his defiance resulted in a war between the Indian soldiers on the one hand and the British troops and their loyalists, such as Punjabis, on the other. Therefore, the British military policy needed a structural overhauling, a well-organised, systematic and planned British Indian Army. But for the British, the recruitment strategy in India needed a major shift from the defiant Bengalis to the loyalist Punjabis. Hence, recruitment from 1857 onwards shifted to the north and north-western regions of India (present–day Pakistan) at the expense of other regions, especially Bengal.

As a result, at the beginning of the twentieth century the British army in India was dominated by the recruited soldiers from the north and north-west of India. Gurkhasfrom Nepal, the Punjabis and the Pathans were preferred. The number of Punjabis increased gradually. The British Army’s senior officers believed that certain classes and communities in India were warrior races – Martial Races. Such classes and communities were believed to prove better and braver soldiers and to be more suitable for army service. It was determined that if India could only afford a small army of 75,000 British (which was reduced to under 60,000) and 160,000 Indian troops for the protection of a subcontinent of over 300 million people, it would be well advised to utilise the best Indian recruits and they were to be found mainly in the Punjab. It was part of establishing a trend whereby the future security and strategy of the subcontinent would be concentrated in the Punjab and not in Delhi, the capital of the subcontinent.

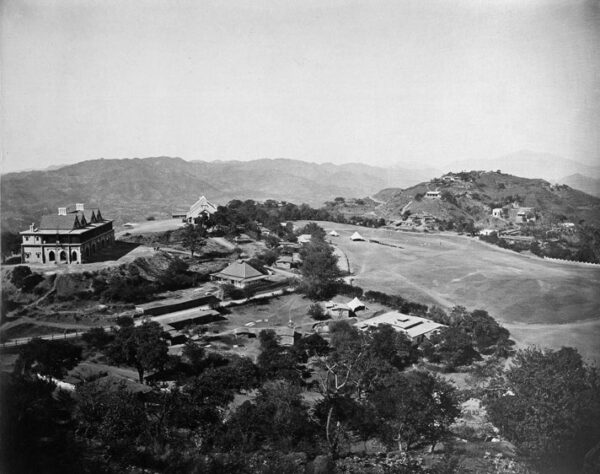

This was one of the reasons that George Miles may have been sent to the Punjab, a region that was then much larger than after the Partition of India in 1947. Subathu was a small garrison village created by the Gurkhas in the 1700’s that was retained and expanded by the British from 1815 onwards. It is situated at the height of 4,000 feet above sea level and only 15km from the nearest rail head at Dharampur. The British rulers would “escape” seasonally to the foothills of the Himalayas for relief from the extremely hot and humid summer climate and the destination that the British Raj made popular was Shimla, about 30km from Subathu. In 1864 Shimla was made the summer capital of British India and headquarters of the Indian army. Twice a year it was necessary to transfer the entire government between Calcutta and Shimla and the track that facilitated horse and ox drawn carts went through Subathu. This meant that another reason for George and his fellow bandsmen being located in this region was most probably to provide musical accompaniment and entertainment for the British Raj. The garrison town of Subathu would have been an important centre for both troops and transport infrastructure and in this small township on the 2nd December 1896, a fifth son, Stanley Alfred Miles was born to Rosina and George.

Stanley Alfred Miles in December 1896

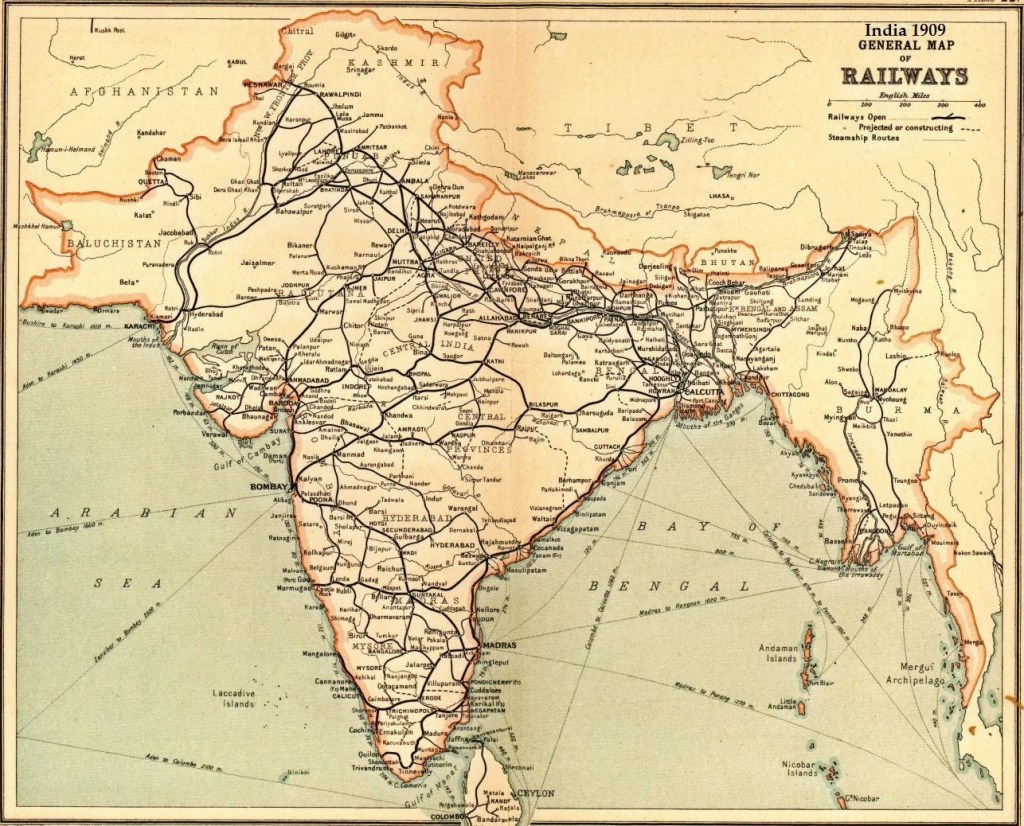

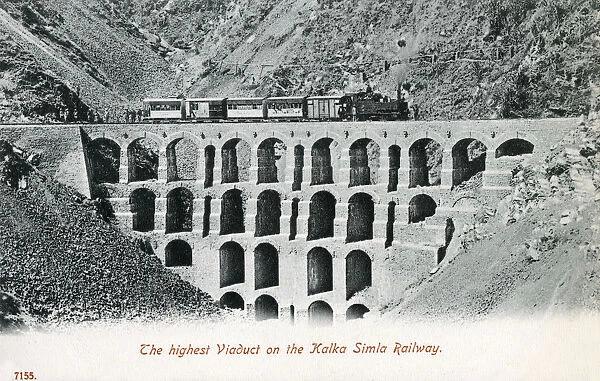

Rail access to Shimla had been surveyed and planned from the 1850’s onwards and in 1905 a rail line, 95km long, was opened between Shimla and a nearby foothills township called Kalka, which had an existing direct rail connection to Delhi.

There was another piece in George and Rosina’s life in the Punjab still to come. About five years before the rail line to Shimla was opened in 1905, George had been transferred to Rawalpindi, a large town 500 kms west of Shimla where on 14th April 1901, a sixth son, Lionel Dudley Miles was born.

an officer with the British Raj. 1905 in Rawalpindi.

Rawalpindi, captured by the British East India Company in 1849, became a major centre of military power of the Raj particularly after an arsenal was established there in 1883. The British army elevated the city from a small town to the third largest city in Punjab by 1921. Islamabad, Pakistan’s official national capital and a planned city, was built in 1960’s, and is almost an extension of Rawalpindi, (less than ten kms apart) both sharing proximity to rivers, lakes and now dams.

In the late 1800’s Rawalpindi was strategically connected by railways to major centres in India (Pakistan was created in 1948) to the east and south and the northwest frontier in Peshawar, the border region with Afghanistan. Under British control Rawalpindi flourished as a commercial centre with a large portion of Kashmir’s external trade passing through it. Rawalpindi was considered to be a favourite first posting for newly arrived soldiers from England, owing to the city’s agreeable climate, and easy access to nearby cooler mountain areas. In 1901, Rawalpindi was made the winter headquarters of the British Northern Command and of the Rawalpindi military division.

Kabul was the major city in Afghanistan and the scene of varying British fortunes in their expansion into this rugged region. The first Anglo-Afghan war in 1842 resulted in expulsion and almost total massacre of the British Indian forces. The second Anglo-Afghan war resulted in victory for the British Raj with increased tensions between Britain and Russia. This was a period where Britain was very concerned about a Russian presence in Afghanistan and Peshawar that might challenge their supremacy. Kabul is only 370kms from Rawalpindi which was the major staging centre for troop movements into Afghanistan during the 1800’s. Large scale riots broke out against British rule in 1905, following a famine in Punjab that peasants were led to believe was a deliberate act.

It was during this time that George Miles, Colour Sergeant of the 4th Battalion of the Somerset Infantry, his wife Rosina and his family returned to England. During the time George served in India, the three eldest sons had all enlisted in the British army in India as “Band Boys”, a practice quite common in military families. Horace enlisted in 1898 at the age of 14; Clifford enlisted in 1900, also 14; and in 1902 the 14-year-old Gilbert continued the trend set by his brothers. They all enlisted for a period of 12 years.

The British Army Pension Records show that George was formally discharged on the 30th November 1907. He had left India at the end of May 1902 and spent the last years of his career at the Taunton Barracks. His Army Record shows that on the 22nd November 1906 he had been granted permission to continue in his service beyond 21 years and that he had given three months’ notice of his intention to take up a job in civilian life. I can only find service records for Horace, the eldest son from 1902 through to the 1911 Census, so I must assume that Horace, Clifford and Gilbert may have all stayed in India for some years after their father had returned “home”. Horace had taken home leave from 27th October 1906 and then returned to India on the 9th March 1907 before leaving India on the 29th October 1908 for service back in England. It also appears that 1908 was the 15 year service/posting mark for the Somerset Light Infantry

Colour Sergeant George Miles accepted a position as an assistant at the Sutcliffe Independent School in Bath, a reform school for boys with its purpose being “for the reformation of juvenile offenders, and of youths in imminent danger of becoming criminal.” The school provided accommodation for staff and about 34 boys aged 11 or over at their time of admission. The industrial training included wood-chopping, tailoring, shoe-making, and farm and garden work. George was described in his discharge notes as having an exemplary character and conduct; and that his special qualifications for employment in civil life were that he was “thoroughly sober and reliable” and “painstaking and industrious”. He and Rosina, with their daughter, Ethel and the two youngest boys, Stanley and Lionel moved into the Sutcliffe Independent School in December 1907.

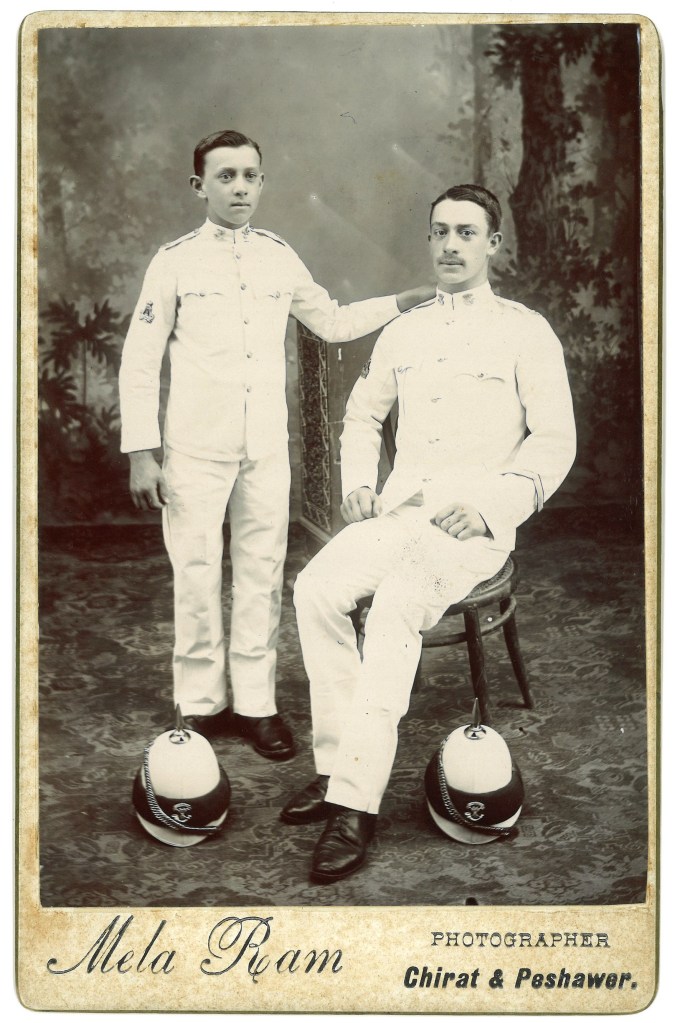

In the same year, 1907, Archibald John Miles enlists in the 1st Somerset Light Infantry as a Band Boy at the Taunton Barracks and appears to join the regiment in India. There is a photograph that is probably Archibald with his big brother, Horace

There is an interesting telegram sent from India on the 8th May 1908 from Clifford Miles to Gilbert Miles which simply says “Horace won the cup x”. I can only assume that this refers to some sporting competition within the Somerset Light Infantry, possibly billiards? Now that this has been won, another reason becomes clear as to why Horace left India at the end of 1908 – he marries his cousin, Elsie Jane Adams on the 15th April 1909 at St Mary Magdalen in Taunton. Elsie, a little older than Horace, is the only daughter in her family – she has six brothers, a similar configuration to Horace’s family. They are related through their mothers – Rosina is the younger sister of Elsie’s mother, Jane Hawkins. The marriage is witnessed by Horace’s siblings, Clifford and Ethel, which suggests that Clifford may have also returned from service in India.

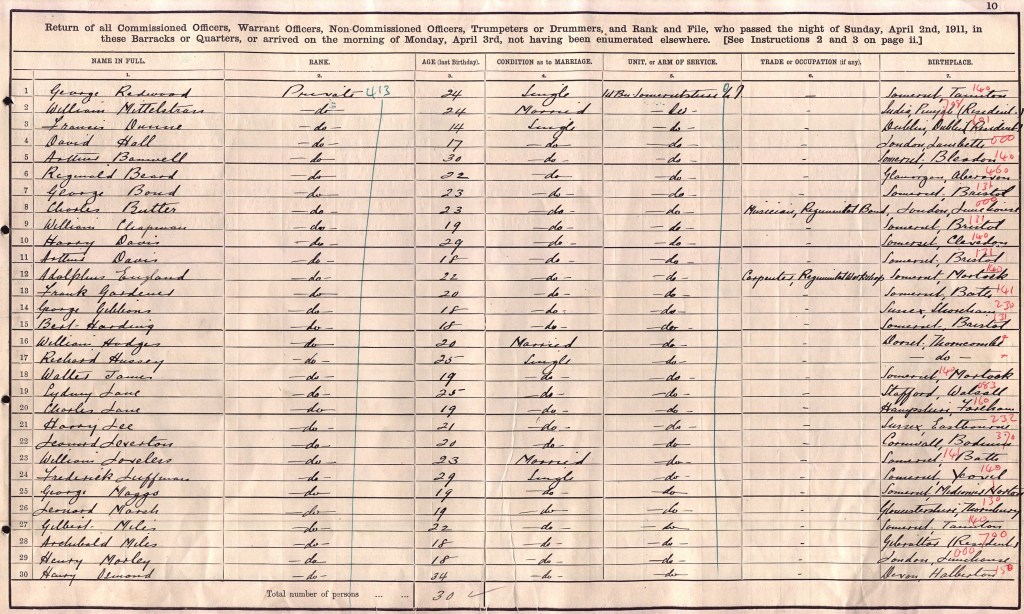

The 1911 Census allows the positioning of the Miles family to be correctly ascertained. George (50), Rosina (51), Ethel Ida (19), Stanley Alfred (15) and Lionel Dudley (9)are all living at Sutcliffe School in Walcot, Bath.

Horace (26) and Elsie (27) have a 3-month-old baby Leslie Horace Miles and are living at 1 St Martins Road in Portland, Dorset. Horace is a corporal with the 1st Somerset Light Infantry.

Clifford (23) is also in Portland, Dorset. He is listed as a musician with the Regimental Band of the 1st Battalion Somerset Light Infantry at a place called the Verne Citadel, which is on the Isle of Portland and was built in the 1860’s to defend the Portland Harbour. By 1903 it had become an infantry barracks and in 1908 became the home for the 1st Battalion of Somerset Light Infantry. All members of the Battalion would have been posted to the Verne Citadel so it is no surprise that both Gilbert (22) and Archibald (18) were living in the Verne Citadel and duly noted on the 1911 Census. The house that Horace and Elsie were living in is also on the Isle of Portland a short distance from the Citadel, so there was probably suitable accommodation provided for army families.

Clifford, Archibald and Gilbert standing;

Ethel, George, Lionel, Rosina & Horace are seated

and Stanley is front and centre.

On the 28th July 1914 Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, and the tenuous peace between Europe’s great powers quickly collapsed. Within a week, Russia, Belgium, France, Great Britain & its Empire and Serbia had lined up against Austria-Hungary and Germany, and World War I had begun. Like so many people, military and civilian, through-out most of the world, George Miles and his family were about to have their lives changed.

George Miles, now 54 years old was immediately recalled to the British Army as a Staff Sergeant Drill Instructor for training purposes. On the 31st December 1917 he was discharged, his records stating “no longer physically fit for War Service”. He passed away in 1929, Rosina in 1940.

Horace Cyril Miles, who had become a father for the second time with another son, Lionel Henry born on the 4th January 1913 had been promoted to the rank of Sergeant in December 1913. The Somerset Light Infantry were posted to different parts of the world – Horace was sent to France on the 21st August 1914 as part of the Expeditionary Force (France) and was not posted “home” until the 18th of January 1919. He returned to the Taunton Barracks and was promoted to the rank of Sergeant Bugler in January 1921. His army records state that he was due for discharge on 23rd of December 1924 after 26 years of service. A consequence of the war was to no longer appoint or support battalion bands, so his rank during the last 3 years of service became Bugle Major.

The 1939 Census shows Horace and Elsie living in Taunton with his mother, Rosina. Horace is listed as a printing works cleaner and porter. Elsie passed away in 1949, Horace in 1959.

Clifford George Miles, who had been discharged from the Army in 1912 was recalled for the 1914-1918 War and had a number of roles. He was a driver for Army Commander at one time and his rank at the end of the war was Lieutenant. In March 1918, in Bath he married Harriet Elizabeth Hillier (1891-1978). They had a son, John Stanley Alfred Miles and the 1939 Census shows them living in Bristol, Gloucestershire, Clifford working as a Motor Driver. Clifford passed away in 1977, Harriet a year later in 1978.

Gilbert Arthur Miles and Archibald John Miles were both serving members of the Somerset Light Infantry at the outbreak of WWI and were both deployed as stretcher bearers in France – as we can see from the article central to this story. Gilbert maintained his rank as Bandsman throughout the war and was awarded the Military Medal for Stretcher Bearing under fire. He married Annie Louisa V King in Bath in June 1917. They had two children and the 1939 Census shows them living in Bath with Gilbert working as a motor mechanic. Annie passed away in 1979, Gilbert a year later in 1980.

Ethel Ida Miles lived in Pembrokeshire, Wales for many years after the war. She married Sidney Thomas Hocking in Somerset about 1920 and had two children, a son George and a daughter Brenda. The 1939 Census shows them living in Wellington, a few miles from Taunton. Ethel passed away in 1951, Sidney’s death date is unknown.

After some initial service in France, Archibald was transferred to the Oxford & Bucks Light Infantry and served in Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq). His rank at the conclusion of the war was Acting C.S.M. He was living in Monmouthshire, Wales in the 1920’s, and married Lilian May White (1893-1988) on 28th April 1920 at St. John’s in Weymouth Dorset. Lilian’s father, Charles White was a Sergeant Major Instructor with the British Army and had served in India where Lilian was born in Bengal. Archibald and Lilian had two children, a son, Francis John Miles (1922-1943) who was born in Monmouthshire and enlisted in the RAF in 1939 and a daughter.

Francis was tragically killed when the airplane he was piloting was shot down over Karlsrhue, Germany on the 26thFebruary 1943.

The 1939 Census shows Archibald living in Southampton, Hampshire and working as a manager of a transport company. Archibald passed away in 1987, Lilian in 1988.

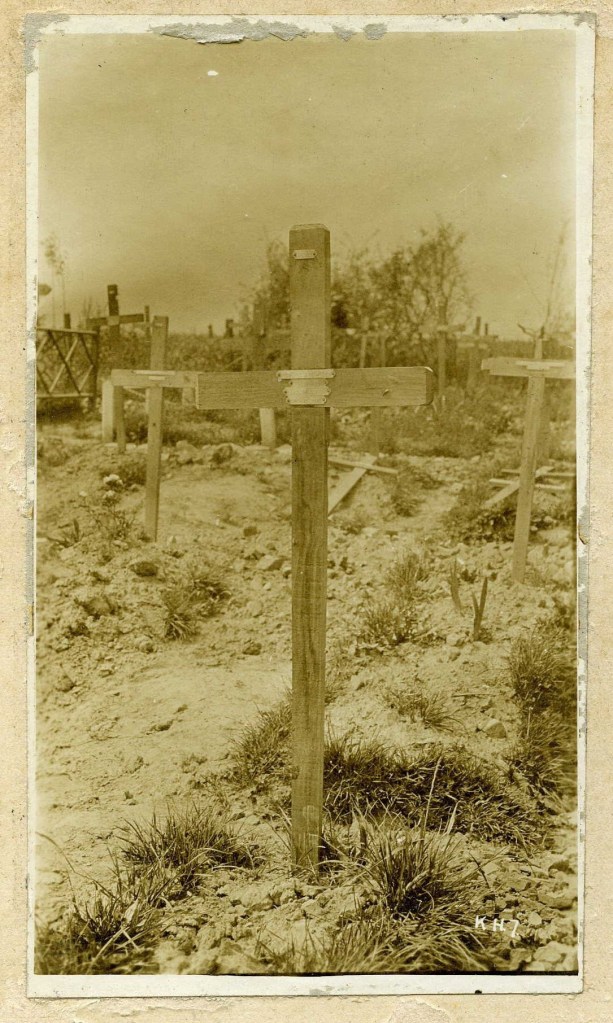

Stanley was a civilian at the outbreak of the war and very quickly enlisted for war service at the Somerset Light Infantry’s base which was now in Colchester. He served in France with the rank of Private and was killed in action in Belgium on the 9th of August 1916, dying from gas poisoning. He was buried at the Ferme-Olivier Cemetery in Flanders, Belgium at Plot 1 Row F Grave 6. He is also mentioned on his parents’ headstone at St. Mary’s Cemetery in Taunton. Stanley was 20 when he was killed.

Lionel Dudley Miles was 12 years old at the beginning of WWI and in September 1917 at the age of 16 he enlisted in the RAF as a clerk. He married Gladys Louisa Maud Lee in Taunton in 1927. The 1939 Census shows them living in Bristol, Gloucestershire with no children and Lionel working as a Master cabinet maker. Gladys passed away in 1980, Lionel in 1993.

The central figure in the September 26th 1914 article is Archibald John Miles a 22-year-old who was born into a military family on Gibraltar. He was the youngest of four brothers who were all serving bandsmen and clarinet players. Archibald lived in army barracks both in Dorset and in India for most of his life and as a professional soldier was probably excited about the prospect of being part of a mobilisation; an army on the move ready to fight enemies of his country. His father had been recalled to be part of the war effort and his younger brother had immediately joined the army leaving his older sister, his youngest brother and his mother as the reduced core of his family in Taunton.

Archibald’s next oldest brother, Gilbert Arthur Miles is mentioned many times in the article, all positive descriptions so we assume that there is a strong sense of camaraderie between the two brothers, particularly as he would be very aware of military process, effort and command. Both Archibald and Gilbert are ranked as bandsmen and described as stretcher bearers. Gilbert was awarded the Military Medal in 1916 for stretcher bearing under fire. Archibald was transferred to another battalion and his rank of bandsman was changed. Did bandsmen always assume the role of stretcher bearer throughout the war?

Captain C.E.W. Bean, the prominent historian and war correspondent from WWI wrote: “Until the First Battle of the Somme many battalions had used their bandsmen as stretcher-bearers. After that battle this system generally was abandoned. For one thing, after such battles the band was too badly needed for cheering up the troops! A battle like Pozieres sometimes made a clean sweep of the regimental bearers. Also, on its side, the work of the bearers was too important to be left to unselected men; they were now specially selected for ‘their physique and guts’”.

Further research found that “The answer to why [bandsmen were stretcher-bearers] is not simple and for every theory there is a contradictory example. In general terms the band initially provided an organisation that was well-suited to performing the medical (stretcher-bearer) role. It had the necessary numbers and rank structure to allow personnel to be distributed among the companies of an infantry battalion. The band was able to train in their medical role while the rest of the unit trained in their infantry role. In action, the band was not required to perform so the band could be employed in other tasks. Stretcher-bearing certainly didn’t offer a safe option. In fact, a number of unit commanders withdrew their bandsmen from stretcher-bearing duties because of the number of casualties and used them in roles such as mortar sections in order to keep a band.’

Other pertinent observations were:

“Most bands were well established and were already a bonded group who would have presented as a unified collection of soldiers ready for training.”

“Bandsmen were of the ‘right sort of stuff’ for the job [of stretcher-bearing, which included battlefield first aid]. They were intelligent and trainable, and not illiterate or semi-literate.”

“Bandsmen were a collection of soldiers who worked together well for training, and of the numbers required for stretcher-bearers for a whole battalion.”

There is no doubt that in battle the role of both stretcher bearer and medic were very important and very dangerous, particularly when the war in Europe descended into trench warfare of mud, disease and terror. It could take four soldiers to carry a wounded man on a stretcher. After some vicious clashes dominated by artillery and machine guns it took the stretcher bearers three days to carry the dead and wounded off the battlefield. There is also no doubt that Gilbert Arthur, remaining in his role of stretcher bearer was a courageous and selfless man, and these qualities are borne out by the descriptions of Archibald and Clifford’s actions in the Bath Chronicle article.

I was intrigued by the references in the article to “Uhlans or Uhlan Patrols”. These were the members of a light cavalry unit who used a lance as their primary weapon. The term originated in the Polish Army in the 1800’s and as well as a lance, the cavalry unit were armed with a sword, or cutlass. The term “Uhlan” developed into a heavy cavalry in western European armies in the 19th century, especially in Germany.

battle order, wearing a gas mask.

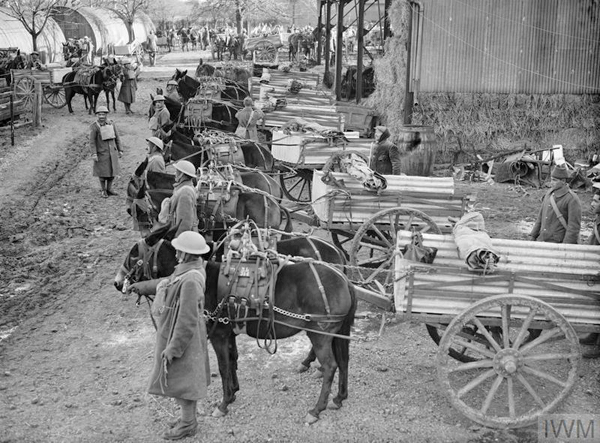

The article also mentions carts as a mode of transport for both troops and equipment. Sometimes they are described as Maltese carts, which appears to mean a simple two wheeled cart that can be moved around by horse, donkey or soldier. There were also many four wheeled carts which, like four wheeled motor vehicles being used increasingly during the 1914-1918 war would often become bogged and stuck in muddy tracks. Rail lines were used as much as possible to transport both wounded troops and ammunition but they did not have the flexibility and capability of simply being dragged, towed or pushed in any direction.

WWI is recognised as the global war which “benefitted” from technology. Airplanes were utilised initially for surveillance and then for bombing and strafing ground troops. Artillery became huge, mounted on rail and requiring equally huge amounts of operational and support troops. Tanks were introduced during this war, a weapon that was deadly on hard ground but prone to continual breakdown in muddy, churned up fields that resulted from the trench warfare. Poisonous, lethal gas was used as both sides came to a standstill in this hideous form of battle. Soldiers were affected by “shell shock” as the horror of trenches killed millions of soldiers and civilians.

The 1884 Maxim Machine Gun changed the course of warfare and shaped WWI. Its inventor was Hiram Maxim, an American-born Britain, who was an inventor of several devices up until this point. Maxim reportedly came up with the concept of a machine gun when he felt the recoil of a rifle. His design pioneered the first recoil-operated firing mechanism.

The first Maxim machine gun was introduced in 1883 and was used by the British Army in several campaigns. Used to terrible effect in WWI, machine guns were the main factor that made “going over the top” in charges nearly suicidal. The machine guns were not a mobile affair; the original gun crew consisted of four soldiers to carry the gun, mount, ammunition and water.

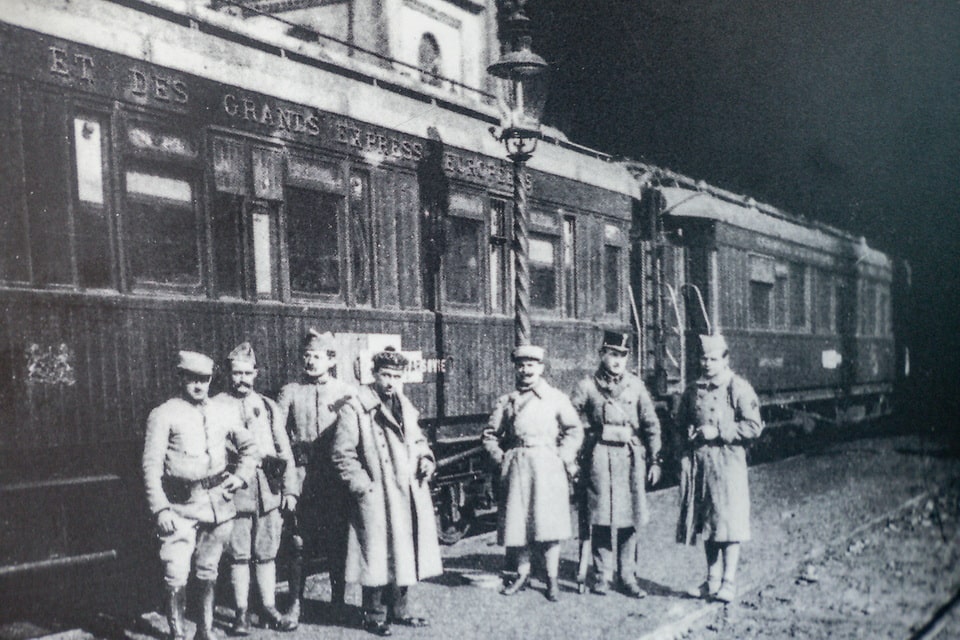

There is a lot of troop movement around trains in the article, and as mentioned earlier, trains and the rail systems were used to great effect during the war. It’s fitting that the war ended on a railroad. When representatives of Germany signed the armistice on Nov. 11, 1918, they sat down in carriage CIWL #2419 of French Marshal Ferdinand Foch’s private train.

The war was formally over, but the Armistice carriage later became a testament to the Entente’s failure to rehabilitate Germany. When Hitler’s forces invaded France in 1940, they forced the French to surrender in the very same carriage.

Archibald Miles endured a wound to his neck, luckily, just to the left of his vertebra. As he said, “A quarter of an inch nearer the centre would have settled me”. Nonetheless, he was bandaged up and instructed to take the carts of wounded soldiers to a station six miles away. The Germans were already there so another march of six miles, then another of nine miles was endured. Then next day a group of 50 wounded and stragglers were entrained for Rouen. After 16 hours Archibald and his fellow soldiers were attended to at a field hospital before being ordered to board a hospital ship “St. Andrew” at Rouen. From there they were taken to Southampton and onto London Hospital for a week’s treatment before a well-earned recovery at Lord Lucas’s estate at Bedfordshire.

Archibalds final words in the article are “It was on my first day in action that I received my wounds, August 26th, and I shall not forget the date, because that just completed my seventh year of service with the Somersets.” The article makes the whole episode seem quite measured, controlled and is surely testament to Archibald’s military background and sense of family.

We are always in awe of ancestors’ resilience and courage in facing difficult passages of time and migration to the other side of the world. This episode involving Archibald and Clifford Miles, as outlined in the Bath Chronicle article only weeks after WWI is declared, exemplifies courage, enthusiasm and a great sense of camaraderie. Most combatants, from both sides expected to be “home by Christmas”. Unfortunately, all soldiers, and their families had to endure five years of danger, fear, uncertainty and horror as their lives were marked by loss and tragedy.

Lest we forget

Leave a comment