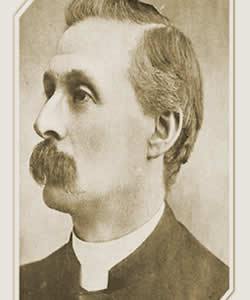

The Reverend John Percival Hoatson (1856-1910)

Vicki’s 1st cousin, 3 times removed.

John Percival Hoatson was born on 16th May 1856 in Halifax, Yorkshire, the son of Joseph Cockin Hoatson and Ruth Smith. He was the fifth child of seven; his siblings were Martha, born in Manchester (1848-1857); Marion born in Halifax (1849-1922); Mary Hannah born in Halifax (1852-?); James born in Halifax (1854-?); Alice born in Halifax (1859-1944) and Annie born in Halifax (1861-1931) Their father, Joseph, had worked as a clerk at Crossley’s Carpet Works, but earlier, in 1847, had been an accountant and sharebroker who had served two months in gaol for a fraud involving his brothers Alexander and John. The youngest of Joseph’s brothers, George, (Vicki’s 2nd Great Grandfather), who appeared untainted by the fraud, became a Congregational Clergyman and departed Halifax for Adelaide, South Australia in 1859. Joseph died in 1863 leaving a young family in dire finances. Fortunately, the wealthy and philanthropic Crossley family (Joseph’s employers) established an educational college and after Joseph’s death, his children were amongst the first to benefit.

The six-year-old John Percival Hoatson became a pupil, then a student teacher at Crossley Orphan Home and School in Halifax, Yorkshire which provided board and lodging, clothing, education and apprenticeships for “children who had either lost both parents or just their father.” The Hoatson children were taught well, with James Hoatson following in his father’s footsteps and becoming a commercial clerk at the carpet works and later an accountant. Alice became a journalist and author, and later a nurse. Her story has been outlined in another narrative on this site. Two other sisters, Mary, and Annie, became respectively, a teacher and a governess. But “our” John Percival Hoatson became a cleric and a rugby authority, his name forever attached to the early development of the game in New Zealand and Victoria.

The founders of the Crossley Orphan School were supporters of various Congregational churches and the Hoatson children’s great-grandfather, the Reverend Joseph Cockin, was a well-known independent dissenting minister who preached at the Square Church in Halifax for 38 years. These influences probably played a significant part in John Percival Hoatson’s choice of an ecclesiastical career. From Crossley Orphan Home John Hoatson, in 1877 furthered his training at New College, a Congregational college in London where he distinguished himself as a theological student. Ill health forced an 18 month leave of absence and a year in South Africa. This experience would leave a lasting impression on Hoatson, one he would retell in print and speeches for decades to come. It is noteworthy that John Percival Hoatson’s 2nd cousin, a Joseph Cockin, (1852-1880) was also a great grandson of the Reverend Joseph Cockin (1755-1828). He also became a Congregational Clergyman, a missionary no less, who died in Bechuanaland, Africa in 1880. Missionaries of this time were driven to save the heathen natives and I’m sure that his death may have featured in John Percival Hoatson’s oratory. Apparently at the time it was rumored that he been killed and eaten by cannibals, but this was not the case.

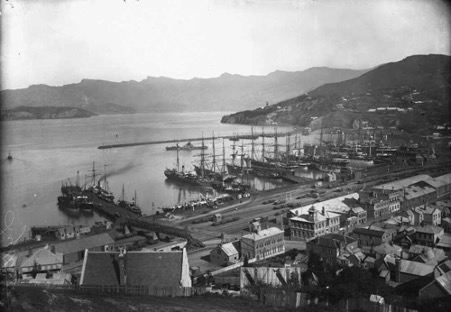

On his return to England, Hoatson was given his first pastorate at Layton Congregation Church, Grange Park Road in June 1881. A tough gig, the church was dogged by internal differences, and was reported to be disorganised and riven with dissension. The Reverend Hoatson had married Kate Walker (1858-1904) on 29thApril 1879 in Hackney, Middlesex before going to South Africa and their family expanded with the birth of two daughters; Florence Mary in 1881 and Winifred in April 1883. Poor health and a church in some turmoil preceded an appointment to the Congregational Church in Christchurch New Zealand. In June 1883, soon after the birth of Winifred, the Hoatson family sailed on board the Pleiades to the South Island of New Zealand, landing at Otago Harbour before travelling up the east coast to Christchurch.

Within three days of arriving in Christchurch, (September 1883), Reverend Hoatson was preaching Sunday morning and evening at the Congregational Church in Philip Street. He was officially welcomed at a tea social and public meeting at an Oddfellows’ Hall later that month. In October Reverend Hoatson travelled south to Dunedin to deliver an address at the Emanuel Congregational Church. In November, and back in Christchurch he delivered an address at the Congregational Schoolroom as part of an evening of entertainment designed to raise funds for the cost of the recent addition to the church building.

By December his congregation had grown to an extent that the building in Philip Street could no longer accommodate, and Sunday Services were shifted to the Oddfellows’ Hall. The less populous evening services on Tuesday remained in Philip Street. 1884 was no less busy for Hoatson, with attendances at the annual Conference of the New Zealand Baptist Union; the Methodist General Conference; and submissions to the Premier on behalf of the Christchurch Ministers’ Association (of which he was Secretary) objecting to the desecration of the sabbath. His abilities as a lecturer and elocutionist had him delivering talks on the works of Tennyson at the Working Men’s Club alongside scientific lectures by Professors Bickerton, Hutton and von Haast; chairing the Anniversary meeting of the Trinity Congregational Church Total Abstinence Society and Band of Hope tea meeting and concert; as well as many local, regional and inter island speaking and preaching engagements, congregational weddings, christenings, and funerals. On top of his regular schedule of weekly sermons he also sang in and directed the church choir. He was a very busy and energetic man!

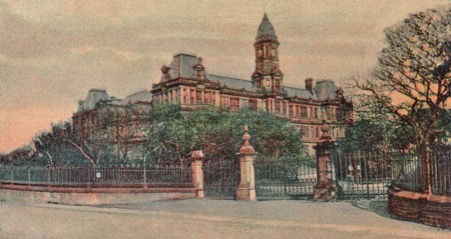

In May, just prior to his 27th birthday and after a relatively short time in the colony, Hoatson’s “christian spirit, genial disposition and attributes” were rewarded with the position of pastor of the Trinity Congregational Church on the corner of Manchester and Worcester streets. A soirée was held to welcome him, with a large assembly for tea in the Trinity Hall followed by speeches and songs from the choir, the Church being prettily decorated with evergreens and an inscription ‘Welcome’, in Gothic characters”. It would seem there weren’t many days or evenings when Hoatson wasn’t attending to the needs of his church, his congregation, and the wider community. What spare time he did enjoy he increasingly devoted to rugby football: as a player, as an administrator and as a referee. He was appointed to referee local football games in 1884 and to the selection committee for the Canterbury Rugby Union in 1885, becoming a well-known authority on the game. The Otago Witness (20 August 1886 & 1 July 1887) made mention of Hoatson’s ability to deliver “a speech full of capital advice to footballers” and that he “is a splendid judge of the game.”

Hoatson was also a highly regarded referee in Christchurch club football, as well as carrying the whistle in inter-provincial and representative matches, including Canterbury’s games against NSW (in 1886), British Lions and the New Zealand Natives team (both 1888).

Apparently well connected in Rugby circles, extracts of Rugby related letters between himself and Rowland Hill, Secretary of the RFU, were published in New Zealand newspapers in 1885. The Canterbury Times (clipped into the Otago Witness on 3rd December 1891) praised Hoatson and the influence he personally had made on the laws of the game:

“As far back as 1885 Mr Hoatson assisted in the selection of the teams to represent Canterbury and in 1887 was appointed sole selector. In a great many ways Mr Hoatson helped to advance the game, especially as a member of the Rugby Union and as a referee.”

“No man in Christchurch had such a thorough knowledge of the rules as Mr Hoatson, and it was largely due to his energy that a number of desirable alterations to the rules were drawn up, and after being submitted to the other Unions in the colony, were forwarded to the English Rugby Union.”

“Some of the alterations were adopted right away, and on various occasions since the parent body has seen the policy of adopting others which are now contained in the rugby rules only in a slightly different form from that submitted by the New Zealand unions.”

Somehow, he also found time to write articles that were published in The Weekly Press and give talks on his reminiscences of the year he spent in South Africa. The family lived in Latimer Square, next to the Canterbury Club in September 1884, then in early 1885 they shifted to a six roomed house at 213 Cambridge Terrace near the Madras Street bridge. In October 1886 Kate gave birth to the couple’s only son, John Percival junior.

On 2nd October 1888 Rev. John Hoatson set sail from Lyttelton on board the Te Anau for Melbourne, Australia to represent Canterbury at the Victorian Congregational Jubilee Intercolonial conference where he would stay with Rev. Jacob John Halley at ‘Irwell’ in Camberwell. Whilst some delegates took their wives, Hoatson arranged that his young family, accompanied by a female servant would spend four weeks at a cottage at Governor’s Bay, where they could spend their days bathing, hunting for ferns or shell gathering before returning to Christchurch.

Reverend John P. Hoatson returned from Melbourne on November 29th on board the Wairarapa via Hobart, Bluff and Dunedin. He travelled in the company of Rev. James Maxwell formerly of the Port Chalmers Congregational Church but at this time he was a Presbyterian minister in mid Canterbury. Kate met her husband at Lyttelton Station in a troubled state and made the shocking revelation to Hoatson that at Governor’s Bay she had been seduced by an Irishman, a Mr. Gilpin, proprietor of the Ocean View Hotel at Governor’s Bay. The following morning, a Saturday, Hoatson left home to arrange a passage for her to return to her parents “by the next steamer” – presumably to remove her from temptation. However, the next evening she told her husband she had met with Gilpin and was going to live with him. Hoatson tried to persuade her to stay but she would not listen.

Whilst Hoatson was dealing with this turmoil in his family life, it was still necessary for him to continue his ministry. Rumors must have circulated but the only one to make the papers was about his having been “offered a pulpit in Victoria”, however, this rumour was quickly and publicly quashed. His lecture series on his “Six Weeks in Australia” pronounced that New Zealand was in a better position than even Victoria to enable a healthy community and a sound, healthy individual life.

On 10th December 1888 Hoatson began divorce proceedings, signing a petition which would be filed two days later in the Supreme Court of Canterbury; On Tuesday 22nd January 1889 solicitors’ clerk Harry Beswick appeared for Hoatson in a suit for dissolution of his client’s marriage to Kate Hoatson, naming John Wilson Gilpin of Governor’s Bay, hotel-keeper, as co-respondent. Neither Kate nor Gilpin filed any objections or made any appearance, and a decree nisi was granted with costs awarded against John Gilpin. It became a decree absolute three months later, on Wednesday, 10th July 1889.

Despite his words about leaving New Zealand, the Reverend Hoatson eventually headed back to Melbourne in pursuit of a pulpit. Hoatson remarried on 16th May 1892 to 25-year-old Christchurch born woman Mary Maude Budden (b. 20th April 1867). The marriage was held at the home of her mother, Mrs. Budden. Mary’s father, Stephen Budden had died a few years earlier. Reverend Hoatson made a final address at the Linwood Congregational Church on 28th May 1892 and with his family sailed for Melbourne on the Waihora on 30th May 1892 so Hoatson could take up the position as pastor to the Congregational Church at Carlton. On 21st April 1893, Mary gave birth to their son, Stanley Budden Hoatson in Melbourne.

The Reverend Hoatson had come to Melbourne just as the football season was closing, but it wouldn’t have taken him long to conclude that Rugby was not played at all in Victoria. As a man who possessed an obvious passion for all facets of the game (the game played in Heaven?), and as some of his later comments would reveal a fervent distaste for Australian rules, he felt compelled to involve himself the sport and it’s development in Melbourne!

Auckland’s Observer wrote on 27th May 1893:

“The Cup matches in connection with the newly formed Rugby Union in Melbourne were to have commenced last Saturday. From the Melbourne Punch I learn that the credit of inaugurating the movement belongs to the Rev. Hoatson, who was ably assisted by Mr Arthur E. Lewis. These gentlemen have been elected vice-presidents of the Victorian Rugby Union in recognition of their services.”

At one of the first meetings of the newly formed NZRU (as reported in Wellington’s Evening Post, 5 June 1893):

“A mass of correspondence from affiliated unions, from English and Australian unions and various well-wishers of the New Zealand Union was read and dealt with. Amongst the letters was one received from the Rev. Mr. Hoatson, late of Canterbury, who has always been a supporter of the New Zealand Union, stating that they had succeeded in forming a Rugby Union at Melbourne, which was progressing favourably and had five clubs.”

“There was also an allusion to the same subject in one of the New South Wales Union’s letters, which stated that the new union having secured a ground and made a good start, there was at last a good prospect of the rugby game taking a firm hold in Melbourne.”

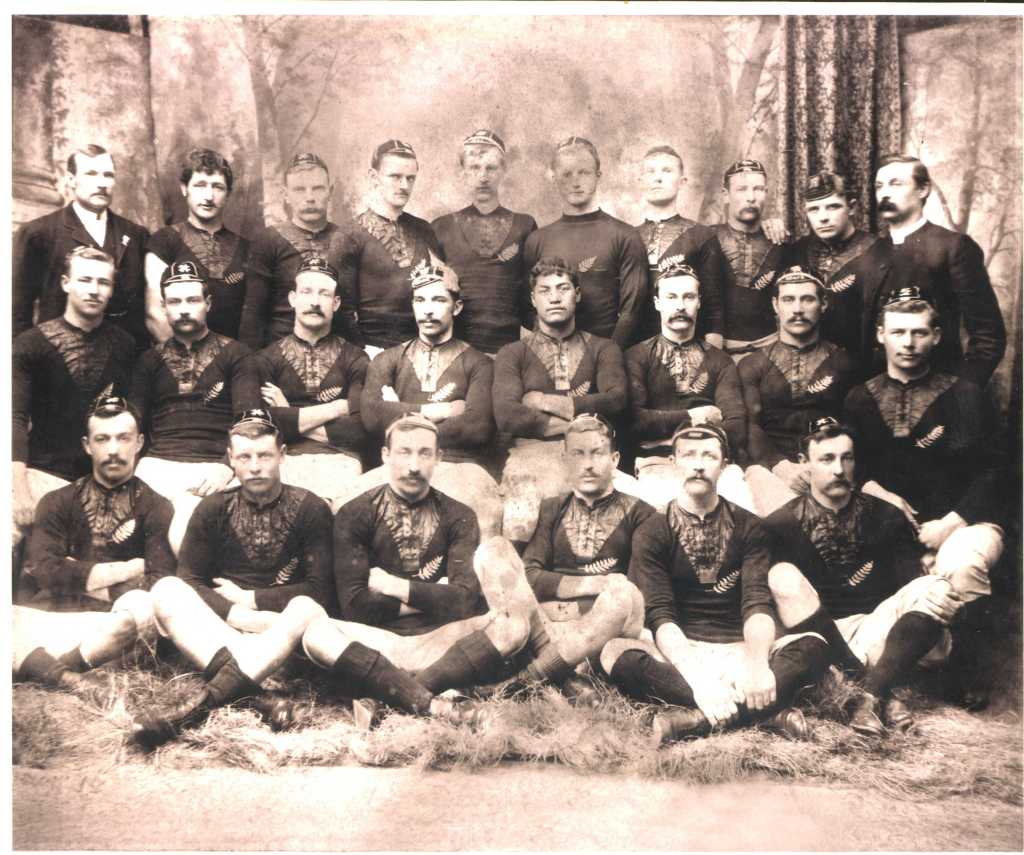

The newly formed New Zealand Rugby Football Union sent a 23-man team to tour Australia in June 1893 for a ten-match tour. Whilst this team was the first ‘official’ national New Zealand selection, it was not fully representative of all the provincial unions. For various reasons, the major South Island unions of Canterbury and Otago elected not to affiliate with the NZRFU until 1894 (Southland in 1895). The touring team was captained by a Tom Ellison and their only loss was to New South Wales 25-3 in the second “test” match. It was not surprising as the team had played four games in eight days. Following the defeat, the managed cabled back to New Zealand requesting four more forwards to boost the tiring team. There was also a lot of heated discussion about the standard and quality of the refereeing in the “test” matches from Tom Ellison and the organisers turned to Reverend Hoatson, requesting that he officiate some of the remaining matches as a solution to the state of vitriol and angst felt by the New Zealanders (Some things just never change!). Reportedly “at great inconvenience to himself” Hoatson accepted the invitation and came to Sydney to control the NSW v New Zealand match at the SCG.

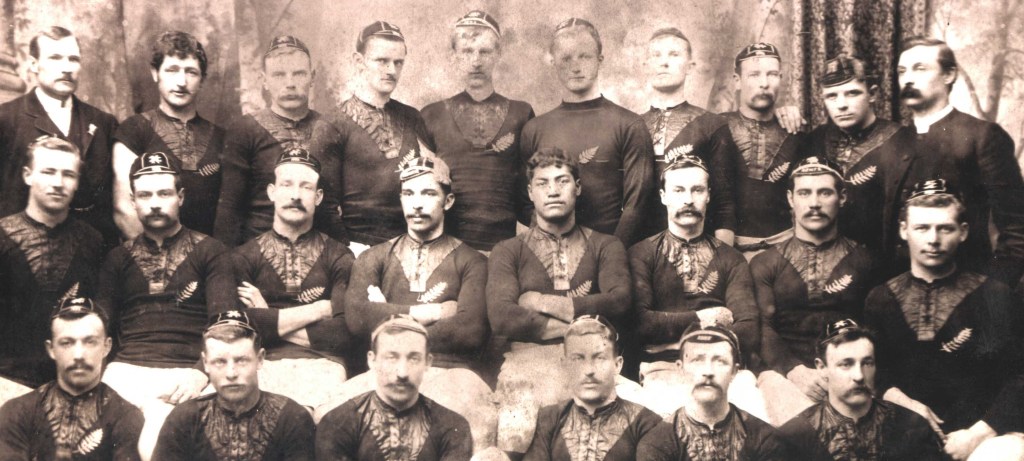

The Reverend John Hoatson is standing on the far right, dog collar and all!

The New Zealand Captain, Tom Ellison Is 4th from the left, middle row.

Reverend Hoatson seemed to meet the expectations of his refereeing as the Otago Witness on 27th July 1893 wrote:

“The Sydney Referee has a good word to say for the ex-Christchurch resident, Mr Hoatson, who acted as referee in the return match at Sydney between the New Zealand Union team and New South Wales:— The Rev. Mr Hoatson, who hails from the old country, and who has for several years been a resident in New Zealand, where he obtained a great name for his umpiring, but who now resides in Melbourne, was the referee, and proved himself the right man in the right place. To him is due the fastness of the game, as he appears to take the rules in the spirit instead of the letter. His decisions were most impartial, and he gave general satisfaction.”

Always a good political and administrative operator, Hoatson, in a speech at the post match dinner reported in The Sydney Morning Herald, 10th July 1893:

“Mr. Hoatson requested if they heard of any Rugby players going over to Melbourne to let the Victorian Rugby Union know, so that they might be able to get hold of those players in Melbourne before they had time to backslide into the slums of the Victorian game.” Not a very nice to say about the growing AFL code! The good Reverend, always an energetic man, was fully involved in the growth of Rugby Union in Melbourne.

Victorian representative teams chosen by Hoatson played against NSW in the winters of 1894-95, and he acted as referee for the matches in Melbourne. Reflecting earlier his words at the Sydney dinner, the majority of the players were not native Melburnians, but those having gained their Rugby education elsewhere. Doubt remains about the extent of Rugby played during 1896-98. Queensland initially intended returning from their New Zealand tour in 1896 via Melbourne to play Victoria, but that failed to eventuate. The Observer (Auckland) reported on 30th May 1896 that Hoatson had again been elected by the Victorian Rugby Union as a vice-president.

It took the news in early 1899 that a British Rugby team would be visiting Australia for the game to again rise in Melbourne, and Hoatson was quickly to the fore.

The Melbourne correspondent for The Referee wrote on 5th July 1899 that “The few lovers of Rugby football in Melbourne have come out of their shells again, and, under the guidance of the Rev. J. Hoatson have formed a club entitled the Victorian Wanderers RFC, in the hopes they may be able to arrange a match with the English team, and also with NSW and Queensland later on,” adding through the rest of July further reports advising that the match was confirmed, that it was now “a club of about 100 strong” and that “the club open their club rooms at 114 Elizabeth Street to-day.”

In the weeks before the arrival of the British team in Melbourne, trial matches were played each Saturday afternoon on the East Melbourne Cricket Ground, with Hoatson acting in the triple role of referee, on-field advisor and selector of the Victorian team. The Victorians also received a letter from the NSWRU opening talks for a proposed game between the two colonies. However, despite their energetic efforts to produce a competitive team, the Victorians were confronted by a British Lions party hardened by two months of matches throughout NSW and Queensland, and the home-side were crushed 30-0. Held on the Melbourne Cricket Ground, as part of a double-bill with an Australian rules match, it was estimated there were 10,000 present to watch the first half of the Rugby contest.

In what surely must be a rarity in international contests, the referee (Hoatson) and one of the captains were both reverends (the British were led by Reverend Matthew Mullineux).

Then, barely weeks later, Hoatson accepted a position as the pastorate of the Congregational Church at Leek, Staffordshire, allowing him the opportunity to return with his wife and two children to England. They left almost immediately, in November 1899.

Though Rugby would have played no part in his decision to leave or not, it is reasonable to conclude that Hoatson departed feeling confident that the city’s 100-member strong Rugby club was the birth of a permanent Rugby presence in Melbourne, and that the promised game against NSW could be readily arranged for 1900.

In May 1900 the “Victorian Rugby Club” played a practice match at the Middle Park Ground (Albert Park), but then no further games were held, and the movement collapsed.

That it could all dissolve away so quickly is a measure of how vital and persuasive Hoatson must have been in encouraging the playing, organising and supporting of the game.

A club Rugby competition was finally established in Melbourne in 1909. Though Hoatson obviously was not involved in that organisation, it seems unlikely it could have come to fruition if not for the underlying legacy of his work and influence on Rugby in Melbourne in its pioneering decade before.

Interestingly, there is no record of John Percival Hoatson ever playing the game of Rugby Union. His health was noted as poor, yet he managed to lead an extremely busy, if not frenetic life in his ministry, lecturing, choir and as an organiser, referee and administrator of the growing sport of Rugby Union, both in New Zealand and in Victoria. He was seen as an expert on the game and a first class referee; but never as a player.

In 1903 Reverend Hoatson wrote to a friend from Staffordshire, England, and in the letter said: “I still hope to get back to New Zealand someday. I have never lost my love for it. It is the finest country I know, and I have travelled in three continents. My advice to all New Zealanders is, never leave your country to live elsewhere.” Hoatson remained the pastorate of the Congregational Church at Leek until his sudden death in 1910 at the age of 52 – only two years older than his father had been at his death.

His first wife, Kate Walker, returned to England and died in 1904 in Bromley, Kent.

This would be why John Percival Hoatson listed Mary Hoatson as his mother and next-of-kin when he entered the war in August 1914 as a Private in the Canterbury Mounted Rifles. His service record shows that he served in Egypt and Gallipoli before his discharge in 1919. John Percival married Kathleen Sykes and died in 1952 at St. Gerrans in Cornwall.

Florence Mary Hoatson died in 1964 in Monmouth shire, Wales. She wrote and published children’s book and poems.

Winifred Hoatson married Frederick David and their son, Alan David was a Hurricane pilot who died, lost at sea, in 1941. Her death details are unknown.

Reverend Hoatson’s second wife, Mary (Budden) Hoatson died in Glamorgan, Wales on the 25th April 1939, her probate listing her effects as 44 pounds and 10 shillings.

Stanley Budden Hoatson married Clarice Boulton and died in 1941 in Hampshire.

Leave a comment